Paragliding in Mosul, a way to shake off recent past

- Published

The northern city of Mosul is used to daily bombings and assassinations

On a perfect spring day, with just a hint of a breeze, conditions are ideal to jump off a mountain, on the outskirts of one of Iraq's most dangerous cities, Mosul.

But would anyone want to do that, particularly in a place where everyday life provides plenty of danger? Well, that is precisely what I came to find out from the Falcon Aviation club, a band of thrill-seeking Iraqi aviators.

In his bright yellow baseball cap, I easily spot their leader, 45-year-old Captain Seba Yasin. A former military pilot who flew in both Gulf wars, he takes every opportunity to pass on his love of flying to the next generation.

"When I was a little kid, I used to build paper planes," he tells me. "The walls of my room were filled with pictures and drawings of planes. If I heard a plane, I would run outside to see it."

His club currently has 200 members, a big improvement from 2003, when most of the club's equipment was destroyed during the US-led invasion.

But it still does not compare to what Capt Seba calls the "glory days", the time during the 1980s and 1990s when support from Saddam Hussein's government made them a force to be reckoned with.

"If you combined all the flying equipment in the Arab world, including the United Arab Emirates that has a lot of money, it would not compare to what we had in the '80s."

A different Mosul

The captain is eager to show how well his club doing. I watch as flyer after flyer is strapped into a harness and run toward the cliff's edge.

False starts are common and occasionally the paragliders crash into the side of the hill, before they are quickly dragged up to try again. But a bump here and there does not dampen their adventurous spirit.

The club has 18 female paragliders

Nineteen-year-old Yaseen is Capt Seba's oldest son, and one of the best flyers on the team.

For his first flight at age 11, his father strapped sandbags around his legs so he would meet the minimum weight requirement.

Today he tells me he loves the sport so much he might "'marry" it. But it also gives him a chance to show the world a different side to Mosul.

"The world does not see Mosul as it is. The world sees it from the outside," he says.

"They focus on the security situation - all the terrorism, the American occupation and destruction. They don't know much about the people of Mosul, how loving and educated they are… the people of Mosul have so much potential."

As the aerial acrobatics continue, I laugh and joke with the club members on the hillside. Their humour and hospitality reminds me of how much more there is to Iraq than just war and conflict.

But the dangers in this country, and Mosul in particular, means it is difficult for Western journalists to meet the middle class people trying to get on with daily life.

Security fears

It has been four years since the BBC's last trip to Mosul, when the team was embedded with the US Military. So, when the city's governor invites me to come see Mosul for myself, I am eager but cautious.

Just in the week preceding my trip in, a police officer was beheaded and nine soldiers were killed in a suicide bombing here.

Mosul has been wracked by violence since 2003

My trip is low-profile. I travel in a car by myself, told not to even wear a seatbelt, to look more like a local. Each time I approach a checkpoint, and there are nearly 15 in just 20km (12.5 miles) , I feel the tension grow. That is where many of the attacks take place.

But eventually I reach the compound, where I receive a warm welcome from Governor Atheel al-Nujaifi, immaculately dressed in a Western-style suit.

A Sunni, he was surprisingly frank with me about his anger with the central government in Baghdad and the army in his city. Both are predominantly Shia.

"We are always calling on them to leave, so that the city goes back to the way it was before. So that only the police are in charge of security as a force that protects civilians. Not an army that treats civilians the same way they were treated by the American forces."

He tells me that his biggest priority is reconstruction, and that security cannot be the only focus, if the city is going to get back to the way it used to be.

He wants to show me his projects to rebuild the city, and I want to see beyond the walls of his compound. But security is a problem for both of us, so instead, I take my leave.

Back on the mountainside, the Falcons continue to try and get things back the way they used to be, in their own unique style.

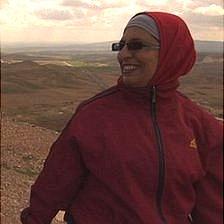

Ghada Adary is one of the 18 female members of the club. Aged 42 and divorced, she took up flying only recently.

"In Mosul we say that a man's heart is like the wind," she says, with a smile. "It changes every few minutes."

But for her, being in the air brings her joy, and a sense of independence. "Out there, you forget everything, everything sad, everything violent. All your mind is on flying. You feel you are free. "

While their day-to-day lives might be different from those of most people, their dreams are just the same.