Why US cannot afford to let Syria situation slide

- Published

- comments

The US and the UK say they will work to strengthen the moderate opposition in Syria and create a transitional body to replace President Bashar al-Assad

After two years of brutal civil war in Syria there is growing support in Washington for the US taking some action.

The question of what to do about Syria's civil war has rumbled away in this city's foreign policy establishment for the past two years, without reaching any sort of conclusion or touching off military intervention, but in recent weeks the ground has been shifting.

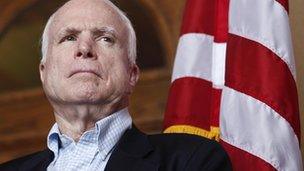

Whereas for much of last year it was a couple of venerable Republicans on the Senate Committee on Armed Services, external, John McCain and Lindsey Graham, who argued the US could not afford to let the situation in that war-torn country slide, there are now signs that a broader swathe of opinion is adopting these arguments.

Does this matter when President Barack Obama seems set against getting involved militarily, reflecting the public opinion of a war-weary America?

It seems that it does, with White House briefing suggesting Mr Obama's administration is now actively looking at sending weapons to the anti-Assad opposition and indeed taking further action if large scale use of chemical weapons emerges.

There have been a number of way points in this change.

There was a significant moment last year when the president's defence secretary and CIA director revealed they had both been over-ruled by their boss on the question of arming the opposition.

More importantly events on the ground such as the reported use of chemical weapons have stirred the debate and created an expectation of action after President Obama's talk of "red lines" for the Assad regime.

It appears it is only the prospect of possible peace talks in Geneva that have stalled the move towards more direct US involvement.

Yet this may simply be buying a reluctant president a little more time to consider unattractive options since at Monday's press conference with David Cameron he showed little faith the diplomatic track would produce something.

In the Senate now other voices, including senior Democrats, are driving the move towards greater action.

Last week Senator Robert Menendez, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, launched a bill to arm the opposition.

Senators Bob Casey (a Democrat) and Marco Rubio (a rising Republican star tipped for the 2016 presidential race) have put forward another, which would mandate the administration to go further, planning to secure Syria's stocks of chemical and biological weapons.

How do these leading lawmakers justify this stance given the experience of Iraq and the marked reluctance of the US public to get more deeply involved?

"We can't just delegate this to others", Sen Casey told me, "we have to have more of an impact on the outcome".

Senator John McCain is gaining support for his quest to arm the opposition

He believes it is a vital US interest to check Iran and Hezbollah (President Assad's allies) in Syria, that the huge refugee flows generated by the conflict are destabilising the region, and America must insure it empowers the moderate Syrian opposition.

Most of these senior people on Capitol Hill who now speak of the need for intervention still hold sacrosanct the principle that there should be no US "boots on the ground".

Yet now that he is gaining broader support for his quest to arm the opposition Sen McCain is urging his colleagues to consider that under certain circumstances, such as a widespread use of chemical weapons, the US and its allies must be ready to send in troops.

"We cannot do this on our own," Mr McCain told us, suggesting that in the nightmare scenario in which nerve gas bombs were falling into the hands of militant groups, a multi-national coalition would have to enter Syria to secure them.

Others, such as Sen Casey, disagree about sending in ground troops, arguing that even under these circumstances, the US would have to limit itself to airstrikes while indirectly helping the Syrian opposition to secure the stockpiles.

So the attempts to halt the conflict by peace talks could hardly be more urgent.

But there are signs that the west's allies in the Syrian opposition could be as reluctant to sit down with President Assad's representatives as they have in the past.

Could a sense that the ground is shifting in Washington be emboldening them to carry on their military struggle?

For a president who has until now been deeply reluctant to fuel the conflict, that could be a bitter irony.

There will be more from Mark Urban in Washington on Newsnight on Wednesday 15 May 2013 at 2230 on BBC Two and then afterwards on the BBC iPlayer and Newsnight website.