Qusair - the Syrian city that died

- Published

BBC's Lyse Doucet was the first western journalist to enter Qusair after it fell and returned a day later to see how it had changed

There is a maxim that's often been invoked in war - to save a city, you have to destroy it.

That has been the fate of Qusair.

Before it was plunged into battle some 18 months ago, it was a thriving border city of 30,000 set in lush groves of olives and apricots.

Now, local officials tell us, only about 500 people still live in a place that lies in utter ruin.

On our second visit to Qusair since it fell to government forces in the early hours on Wednesday, we found a calmer place, with none of the edginess or frenzied celebration we witnessed in the immediate aftermath of battle.

There is more traffic on the streets but it is almost all soldiers travelling in tanks and trucks, on motorcycles and bicycles.

Most are piled high with mattresses, TVs, fridges and furniture as soldiers move from one abandoned building to the next, taking away as much as they can carry.

We only came across one family returning to their house. They fled a year ago when rebels captured Qusair. They came back to a place they didn't recognise as home.

Metal shutters are peppered with holes from bullets and shrapnel. Walls and ceilings are punched with gaping holes.

And the floors are strewn with remnants of the rebels' lives.

Blood group lists

Abu Samar sifts through one pile and holds up a rifle scope, a holster for a pistol, someone's notes from classes in Islamic teaching, a games console. Shirts with symbols of the Free Syrian Army's Farouk Brigades are thrown on a chair.

Taped to the wall is a handwritten list of the blood groups of fighters who lived here.

Syrians of many faiths once lived together in Qusair

Abu Samar's wife quickly bundles up possessions her own family had left behind, including children's stuffed toys, glass plates still in their boxes, and plump cushions.

"Will you come back here to live?" I ask.

"No, never," she declares, fighting back tears.

They quickly drive away in a car bulging with their goods through a city where every house on every street is as ravaged as their own.

But even more worrying than Qusair's immense physical damage, the social fabric of society has been ripped apart.

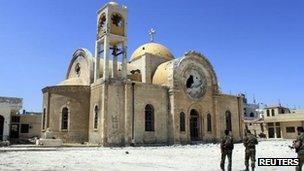

Down a desolate street, a battered Church of St Elias symbolises how many Syrians of many faiths once lived here together.

This Christian place of worship has not just been destroyed, it's been desecrated by the fighting.

Its marble floor is now carpeted in rubble and broken glass. Religious icons are defaced, prayer books burnt, the altar smashed.

On the other side of Qusair, next to a shattered hospital used over the past year by both sides as a base, we ask a group of soldiers about the terrible price the city has paid.

"It pains me to see these ruins," says one young man doing military service who wears civilian clothes.

"This hospital cost a lot to build, from the taxes my family and other families paid."

"People will return," insists another young soldier who joins our conversation. "They will come back to a city that will be even better, and their lives will be even better than before."

They all blame the rebels for this wasteland of war.

"This is what they call freedom," declares a soldier who stops to show us improvised artillery pieces wrapped in cling film and packed with explosives.

"They use these against us because they hate us."

The Syrian troops were joined by Hezbollah fighters in the city

The battle lines in Qusair and across much of Syria are harshly drawn along political and increasingly sectarian lines. They're even more defined now that Hezbollah fighters from neighbouring Lebanon have publicly joined forces with Syrian troops.

They move openly in the streets of Qusair. One man boldly approaches us wearing a headband in the movement's distinctive yellow and green colours, and a ribbon around his wrist.

I ask about the latest battle.

"It wasn't hard," he confidently replies and then confirms reports that Lebanese fighters are now going in and out of Syria on rotation, moving across a border so close you can see it from the edges of the city.

"It was easy as pie," boasted another as he challenged me to guess his nationality.

I ask some Syrian soldiers what they make of the controversial presence of Hezbollah.

"Why shouldn't they fight with us?" one demands. "The other side is sending in fighters from Libya, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Afghanistan. Half the world is fighting in Syria."

Qusair made headlines across much of the world as a small city at a strategic crossroads became a precious prize in a bitter battle.

The people who called it home are now scattered in neighbouring villages, in schools and on the streets. Some fled across the border to Lebanon.

We still don't know how many were killed in the last three weeks of fighting. But what we have seen is a city that's died.