Lina Sinjab: Emotional farewell to Damascus

- Published

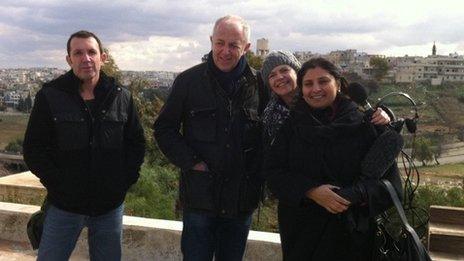

Lina Sinjab (right) and her BBC colleagues in the city of Deraa

The BBC's Lina Sinjab explains her deep emotion as she leaves her ruined home city of Damascus, where she has been reporting on the Syrian conflict for the BBC for the past two years.

Damascus, the city I grew up in. The city of jasmine trees, of spice markets and covered bazaars, the city of the Barada river and a history that goes back thousands of years.

It is no longer the same - it is completely different. I have covered the revolution since it started in March 2011, and I've kept my feelings for this city even as it has changed before my eyes.

Everyone thought that Damascus would be immune from the violence. That what is happening in neighbouring cities and towns would not affect the capital.

But they were wrong. Damascus has become another hot spot, witnessing government violence against peaceful protesters.

At the beginning, the regime managed to rally a lot of supporters behind the leadership of President Bashar al-Assad.

There used to be lots of rallies chanting for Assad: "Long live Assad", "God, Syria, Bashar only".

Then they became: "Either Assad or nobody", then "Either Assad or we will burn the country".

Today the slogans read simply: "We will burn the country."

For Assad loyalists, who are mainly from his minority Alawite sect, his survival means the survival of the sect itself.

Tanks frequent the district of Jobar, where Lina Sinjab's family lives

Rain of mortar rounds

Society has become polarised; friends separated; families in dispute as everyone is on one or other side of the conflict. The dynamic of life has changed. Everyone is trying in their own way to adjust to life in a city in the grip of war.

It has become a luxury to go back home alive. Everyone in the city knows that at any minute they might be dead. Or someone around them might be killed in the crossfire, or because of the mortar rounds that have started to rain over the city.

In Abbassien Square, on the fringe of the southern suburbs, you can see the military operation in full force.

The sports stadium has been turned into a military base - there are tanks and loads of soldiers, and from the square I saw a tank - with my own eyes - not parking but actually firing at the Jobar district. My family lives two streets behind that tank.

I was confused about how to feel about it. Somehow I was laughing. I don't know if it is anger that has been transferred into laughter; or a sense of helplessness that others are being killed and there is nothing I can do about it; or the selfishness that I am lucky that I'm still behind the tank, and still have time to live.

I suddenly realised that I had stopped crying, stopped feeling, a while ago.

But I want to cry every death, I want to regain my humanity and soul. I want to regain my heartbeat. I don't want to befriend death, I want life.

Like Stalingrad

I have visited many cities during the conflict. I saw the protest in Homs, with the football player Abdulbaset Sarout chanting for the country and freedom, with men and women dancing to his voice in the streets.

I saw young Christians and Alawite activists visiting suburbs of Damascus giving condolences to families who lost their children after being shot by government forces.

I followed women lobbying for peaceful change in the country going door-to-door and neighbourhood-to-neighbourhood helping out with humanitarian and psychological support for people traumatised by the war.

But even a single peaceful move, like holding a red banner in the covered market that writes, "Stop the killing, we want to build a home for all Syrians", was a reason for detention. Let alone being on the front line, and bearing arms against regime forces.

People have to keep living their lives amid the destruction of Douma

Douma, a suburb of Damascus, was the first place to come out in support of Deraa, where the uprising began. The Douma protests were completely peaceful.

A conservative district, it witnessed a social revolution before the political one. Women revolted against the norms and stood hand-in-hand with the men in the streets calling for freedom.

But today it resembles Stalingrad in destruction.

The civilians who remained there have been marked by the conflict.

A 14-year-old boy who left school and became a nurse tells me he would have been speaking fluent English had he been able to stay at school.

He told me he lived with blood and wounds every day. But he was strong. And as the warplane flew over while we were talking, he told me he was not afraid of death: at least he could speak freely now.

Never the same

We created ways of surviving. We were cooking, drinking, singing and laughing.

We were making jokes of the war, of our fears, criticising the government and the opposition.

Not a single day passes without a social gathering with friends. It is bizarre how the war makes you appreciate every person in your life: you get closer to people, you learn to speak about fears and weakness and laugh about them - probably this keeps us going.

We cannot afford to be sad and weak, the only way is to stand up and move on.

After a year of being prevented from leaving the country, I got my passport back and it was time to leave. I said goodbye to the last friend.

The situation in Damascus is getting worse by the day. Something deep inside everyone is saying goodbye, and we don't know if we will see each other again.

I don't know what will happen to my city and those who remain in Syria. I left Damascus with a broken heart and soul, left my memories, my life, every single detail is there, every friendship and every story.

I am not sure when I will be back and if I am ever back, I worry it will never be the same city I grew up in.

You can hear Lina Sinjab's intimate feelings on leaving Damascus in the Assignment programme Damascus Diary