How Geneva II could be worsening chances of Syria peace

- Published

- comments

The population of Qusair - once a thriving city set in lush groves of olives and apricots which now lies in utter ruin - has fallen from around 300,000 people to just 500.

The US and UK are looking with renewed urgency at the possibility of sending arms to the Syrian opposition. Insiders say that this comes in response to recent successes by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's forces, notably in Qusair where they were helped by Lebanese Hezbollah militiamen.

However, the briefing about weaponry may also indicate the effective ending of hopes for a Syria peace conference, dubbed Geneva II by diplomats.

In Moscow in early May the US Secretary of State John Kerry and his Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov, announced they would co-sponsor a resumption of negotiations begun in Switzerland last year. It was Mr Lavrov's task to bring Moscow's allies in Mr Assad's camp to the table, and America's to deliver the Syrian opposition.

The two men talked of their hopes of getting the conference together before the end of May, then when that seemed unrealistic the chatter was about the second week in June. Now there are vague suggestions about July.

In May, US talk of supplying arms to the resistance, following reports in April about chemical weapons, was shelved with the White House briefing the issue would be set aside until after Geneva II. The British meanwhile argued that ending the EU arms embargo was a step designed to incentivise negotiation.

On one reading, statements by US and UK officials actually could be argued to have given the Syrian Coalition reasons to hope for the failure of the diplomatic process. For, if everything went to plan diplomatically, the rebels would get no arms from them.

Certainly the disparate groups that make up the coalition (and there are important militias such as the Jabhat al-Nusra that are not even notionally part of it) were soon placing conditions on attending the Geneva and splits within what is a loose alliance at the best of times widened.

When I suggested to one senior figure at the recent Cameron/Obama White House meetings that they would have a hard job delivering the Syrian opposition for Geneva II, he told me, "We have many different points of pressure we can use on them".

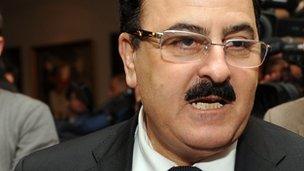

Gen Idriss says his men can topple President Bashar al-Assad if they receive help from overseas.

But barring an astonishing turn around, Mr Kerry's Moscow offer to achieve this goal seems destined to fail.

Now Gen Selim Idriss, the Syrian coalition's military head, says the idea of attending the Geneva conference is, "a joke". He has appealed for arms immediately in order to forestall further offensives from the Assad government and its Hezbollah allies. So much for US/UK "pressure points".

In Whitehall people are split about the wisdom of sending lethal aid. Much legal, military, and foreign policy advice is opposed, but Downing Street is much more open to the idea.

"We are close to being back where we were in the 1980s [with the mujahideen fighting the Soviet Army in Afghanistan], supplying weapons to Islamic extremists," one insider told me on Monday. He suggested man portable anti-aircraft missiles were high on the list of possible UK transfers.

As to what might be gained by doing this, some Machiavellian arguments are doing the rounds in Washington and London. The intelligence people and foreign policy advisers in both countries are scathing about the ability of the disparate opposition groups to concert an effective strategy, and resigned to Western-supplied arms going to "undesirable" groups.

"We cannot allow Iran and Hezbollah to win this one," a one-time Downing Street staffer has told me. Others have suggestions about using Syria as an arena to do to Iran what the Islamic Republic did to the US and UK in Iraq.

It seems then that there are many who now believe the supply of weapons is necessary to prevent the resistance to Mr Assad going under. In other words a measure once advertised as a means of getting people around the negotiating table has become a way of prolonging the conflict.