Iran's Hassan Rouhani: Key challenges

- Published

Hundreds of thousands of people across Iran poured out on to the streets in celebration when national television announced that cleric Hassan Rouhani had won the presidential elections.

Many were also celebrating the end of the era of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, shouting: "Bye bye, Ahmadi!"

Many believe Mr Ahmadinejad, elected twice in controversial elections, has put Iran on the path to economic ruin and confrontation with the outside world.

Mr Rouhani won a respectable mandate with the promise of pulling Iran back from the brink, helping to end international sanctions and reversing soaring inflation. But can he deliver?

Here are some of the key issues he will have to face as he takes office.

Political prisoners

Although Iranians are under severe pressure from soaring prices and unemployment, the immediate demand from many for the new president is the release of political prisoners.

Leader of the opposition Green Movement Mir Hossen Mousavi remains under house arrest

This has been clear from the slogans in the street celebrations immediately after the announcement of Mr Rouhani's election, as well as in rallies during the election campaign.

There are, according to an investigation by the UK's Guardian newspaper, close to 800 political prisoners, as well as prisoners of conscience, in Iran today.

The best-known are of course the leaders of the opposition Green Movement, Mir Hussein Mousavi, his wife, Zahra Rahnavard, and Mehdi Karroubi, who have been under house arrest without trial for the past two years.

But they also include journalists, lawyers, human rights activists, bloggers, feminists, Christian priests, Sunni clerics, the entire leadership of the Bahai faith in Iran, and others.

Whether Mr Rouhani can secure their release will be the first test of his authority. Their release would also ease the atmosphere in Iran, putting an end to the prevailing political repression.

Relationship with the Leader

On many issues, whether Mr Rouhani can deliver will depend on his relationship with the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has the last word on many areas of policy

Ayatollah Khamenei is effectively the leader of the Islamic hardliners, and has the last say on many crucial and strategic issues.

But Mr Rouhani is not exactly a liberal either. He has held senior positions for many years. He is an insider.

While Mr Rouhani needs the hardliners to co-operate, the hardliners need Mr Rouhani to save the regime from the deep trouble it finds itself in as international sanctions and mismanagement of the economy erode its authority at home.

Mr Rouhani seems to be someone the Supreme Leader might be able to do business with.

And we must not forget that the mandate for change and moderation that Mr Rouhani has received from the electorate represents a big rebuff to the isolationist and extremist policies of the Supreme Leader. The vote considerably weakened Mr Khamenei's position.

The economy

With a negative growth, the economy is in recession. The rate of inflation is officially nearly 36%, unofficially much higher.

Food prices have been amongst the worst affected by a recent spike in inflation

Inflation for food prices has reached 55%. Unemployment is around 12% and rising. The mismanagement has been monumental, but international sanctions have wreaked havoc too. Sanctions on Iran's oil exports have reduced its main source of income by about 65%.

Banking sanctions have had an even more disruptive impact on Iran's trade with the outside world, making it impossible for Iran to bring its petrodollars back into the country - hence the shortage of hard currency that has led to a huge drop in the value of the Iranian rial, by about 80% in the last year.

Mr Rouhani can hope to improve management in some parts of the economy - he can hardly do worse than before. But he needs to end the sanctions if Iran is to be put back on the road to recovery.

The nuclear stand-off with the world powers

During live televised debates in the run-up to the elections, almost all the candidates, even Islamic conservatives and hardliners, criticised another candidate, Saeed Jalili, for squandering chances at several rounds of talks between Iran and world powers on Iran's nuclear issue.

Saeed Jalili (far right) was accused of not making enough progress as Iran's chief nuclear negotiator

Mr Jalili, who came third in the elections with about 11% of the votes, has been Iran's top nuclear negotiator since 2007.

He was accused by the other candidates of failing to make progress in international talks, leading to more sanctions being piled on Iran.

It was clear that even right at the top of government, there are deep divisions on how to proceed at these negotiations.

Mr Rouhani has said that it is possible for Iran to maintain its nuclear programme and at the same time reassure world powers. He has suggested that Iran may be more proactive in the talks, and more transparent in its nuclear activities. He said he wants to arrive at a position of mutual trust with world powers.

All this are easier said than done. But if he finds a way, he may well have the backing of Iran's Supreme Leader. If not, the spectre of war will continue to hang over Iran.

Relations with the outside world

This is an area where the new president will be able to make his mark more easily than on other issues he faces.

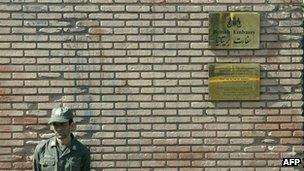

Mending fences with the UK might be one starting point for Mr Rouhani's foreign policy

He has promised to improve relations with the outside world. He has the diplomatic experience, having been for some years Iran's top nuclear negotiator, dealing with Western powers at the highest levels.

He could begin by re-establishing links with Britain, which closed its embassy in Tehran in 2011 after a mob attacked the compound in Tehran. Britain then ordered the closure of the Iranian embassy in London.

The first American reaction to Mr Rouhani's election was to offer direct talks with Tehran on Iran's nuclear programme as well as on bilateral relations. In the new euphoric atmosphere in Tehran, many feel that anything is possible.