Iran's foreign ministry struggles with online PR

- Published

Marzieh Afkham and Mohammad Zarif are realising the power of social media

A hardline backlash always looms large over any attempt by a new government in Tehran to present itself as one that the West can talk to.

President Hassan Rouhani has already found that the greatest challenge to public diplomacy is an apparent lack of discipline, rather than a lack of influential allies or favourable laws in a country where Facebook and other social networks are banned but not illegal.

From conducting diplomacy via Twitter to appointing its first female spokesperson, the foreign ministry has not shown a particular aptitude for online PR.

This is important for Mr Rouhani because he has convinced the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, to allow the foreign ministry to take charge of negotiations with the international community over its nuclear programme, starting in New York later this month.

Unofficial accounts

The new man at the helm of the foreign ministry is Mohammad Javad Zarif.

As Iran's permanent representative at the United Nations between 2002 and 2007, Mr Zarif earned the respect of senior US officials when he worked to ensure talks between Washington and Tehran took place despite the efforts of hardliners on both sides.

Twitter says it has verified Mr Zarif's account

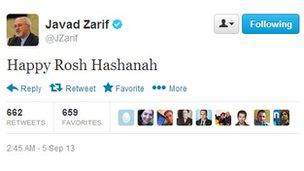

Mr Zarif is one of the few cabinet members with his own Facebook page and Twitter account, which he used last week to wish Jews a "Happy Rosh Hashanah".

He also used Twitter to assert that the Iranian government had never denied the Holocaust, adding: "The man who was perceived to be denying it is now gone."

He was referring to Mr Rouhani's predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who during his eight-year presidency frequently claimed the Holocaust was a lie.

Mr Zarif's tweet made headlines, but not as many as an earlier one that also wished Jews a happy new year, which appeared to come from the president.

Mr Rouhani's office was swift to tell reporters that the message had come from an account set up by a supporter, and was not an official statement.

However, some critics expressed scepticism, claiming that Iran's reformist politicians were intentionally muddying the waters over who operated social media accounts in their name so they could test public opinion and disavow messages that angered hardliners.

'Absurdity'

The foreign ministry's decision to appoint a female spokesperson was a deliberate signal to both its domestic audience and the international community. But it began with a PR blunder.

Within a week of Marzieh Afkham's appointment, her supposed Facebook page received 25,000 "likes" - a huge figure in a country where access to the site is blocked.

As it turned out, a week later the whole venture was a hoax carried out by an exiled activist.

President Rouhani has given the foreign ministry responsibility for Iran's nuclear negotiations

The foreign ministry initially did not react, but Ms Afkham was forced to deny any link to the page when domestic media began reporting about it and quoting posts.

The magnitude of the problem became apparent when one minister complained that the press was routinely quoting social media accounts that were not theirs.

Hardline rivals were quick to ridicule reformist politicians for "reducing public diplomacy to absurdity", arguing that they could not handle internet freedom, for which President Rouhani has campaigned.

Hoping to prevent confusion and achieve more clarity and discipline in its conduct on social media, the government set up a special committee to deal with unofficial social media accounts. However, this suggested that they had never considered the issue to begin with.

When it comes to social media, Iranian intelligence and law enforcement are on top of their game.

The same cannot be said of the foreign ministry and reformist politicians, whom after eight years away from power are just beginning to realise what social media can do.

The Afkham affair may also present a lesson for hardliners as well, considering that the Supreme Leader's own Facebook page, with 56,000 likes, is also officially not his own.

- Published6 September 2013

- Published5 September 2013

- Published19 December 2012