Legacy of 1973 Arab-Israeli war reverberates 40 years on

- Published

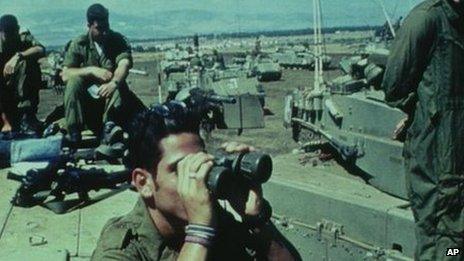

Egypt and Syria caught Israel off-guard when they attacked on the holiest day of the Jewish calendar in 1973

Israel closes down for the fasting, repentance and prayer of Yom Kippur - the day of atonement.

So complete is the suspension of everyday life that traffic stops and normal broadcasting is suspended.

It is the holiest day in the Jewish calendar - and Israel's moment of greatest vulnerability.

In 1973, Egyptian and Syrian military planners chose it as the perfect moment for a combined surprise attack on the Jewish state - the war changed the world and we all live with its effects to this day.

The Arab attacks were an effort to reverse the humiliating defeats of 1967 in which Israel had redrawn the map of the Middle East with stunning speed.

The Israelis captured the vast Sinai Desert from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria and the West Bank of the River Jordan and the eastern part of Jerusalem from the Jordanians.

Egypt and Syria at least were determined to recapture their territory - and to restore national pride.

The BBC's Kevin Connolly has been back to the battlefields of the war of 1973

The Egyptian General Sameh Elyazal was a young officer injured when his tank was hit by a missile fired from an Israeli aircraft in the war of '67. He has a piece of shrapnel lodged inside him to this day.

He explains the thinking in Cairo in 1973 like this: "When we came back from '67 you could feel the way people looked at you .... as if to say 'you don't deserve our respect'. Even our families were saying that our country deserved better so we thought we have no other way of correcting this impression than getting the Sinai peninsula back."

When the attack came Israel was stunned. Out of nowhere it found itself facing a war of national survival on two fronts.

In the south, Egyptian commandos crossed the Suez Canal heading eastwards into the Sinai capturing the Israeli forts along the eastern bank of the Suez Canal. In the north, Syrian tank regiments swept on to the Golan Heights.

Future Israeli PM Ehud Barak rushed back from the US on the outbreak of war

The Israeli commanders scrambled to mobilise their reserves - the national radio service which had fallen silent for Yom Kippur began broadcasting a special news bulletin punctuated by code words that recalled soldiers to their military units.

The future Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak was a graduate student at Stanford University in the United States in 1973.

But he'd already served as a commander in Israel's elite commando unit the Sayeret Matkal and as soon as he heard the news from home he packed his bags and said goodbye to his wife and young daughter.

When he got home he headed straight for the underground bunker known as The Hole from which Israel's armed forces are run. The atmosphere wasn't good.

"I saw faces grey like dust," Barak says now, "It was one of the lowest points of the war."

Gradually Israel's forces began to rally - and to gain ground as they counter-attacked. But the complacency that was a dangerous by-product of the easy victories of 1967 was punctured and so was the sense of invulnerability which had gone with it.

Cold War

Then, as now, events in the Middle East mattered - and resonated far beyond the region.

In the early 1970s the Cold War was at its height and just about any theatre of conflict on earth was effectively a proxy war between the Communist Soviet Union and the power bloc that styled itself the Free World, led by the United States.

Egypt won the Sinai back through diplomacy - signing a peace treaty with Israel in 1979

Russian military 'advisers' went into combat with the Syrians and supplied arms and ammunition to the Arab nations.

The United States backed Israel. The bottom line was that the Israelis had chosen - or been chosen by - the right superpower. The Americans made better weapons and they were better at getting them to the war.

So the tide of battle turned and after at least one false start ceasefire negotiations eventually produced an end to hostilities. When it came, Israeli forces were not far from the gates of Damascus and were only 100 kilometres from Cairo.

The war had been short, but it changed the world.

Fuel shortages

Arab oil exporters who dominated the global energy market at the time decided to punish the West for backing Israel by using what it called ''The Oil Weapon".

Prices were suddenly hiked and output was cut.

There were fuel shortages, a stock market crash and a global economic slowdown whose effects were felt for years. The 55 mph speed limit on some federal roads in the United States dates from the period when desperate attempts were made to save fuel.

Europe and the United States began cultivating alternative oil suppliers and thinking about alternative energy and fuel saving. The death knell was sounded for the gas-guzzling car.

Most of the Golan Heights were captured by Israel from Syria and occupied ever since - Israeli tanks are seen on manoeuvres here in 1991

Diplomatically Egypt drifted out of the Soviet sphere of influence and became an ally of the United States.

It got the Sinai peninsula back in the end but through diplomacy, not war - under American chairmanship it signed a peace treaty with the Israelis a few years after the guns fell silent. The Camp David accords were one of the most important diplomatic achievements of the post-war era.

The Arab nations probably concluded privately that they would never defeat Israel in a conventional war. The fighting may have seen some of the last major tank clashes of history. Armoured vehicles it turned out were too vulnerable to missile fire from aircraft.

But Israel was forced to conclude too that it couldn't take easy victories for granted and that the Egyptian army in particular could stand and fight.

In the period of introspection that followed the war and the intelligence failures that led up to it, senior politicians and military officials lost their jobs.

But the most depressing legacy is perhaps this.

If you go up to the Israeli side of the ceasefire line on the Golan Heights today you can find ruined and abandoned armoured vehicles preserved as monuments.

You can look into Syria and watch and listen as the Syrian army directs tank and artillery fire onto towns and villages where it claims rebel forces are hiding out.

It is evidence of how close the Syrian war has come to history's old battlefields - and a reminder that, in the Middle East, the uncertainties of the future always feel more pressing than the glories and the agonies of the past.