Growing suffering of Syria's besieged civilians

- Published

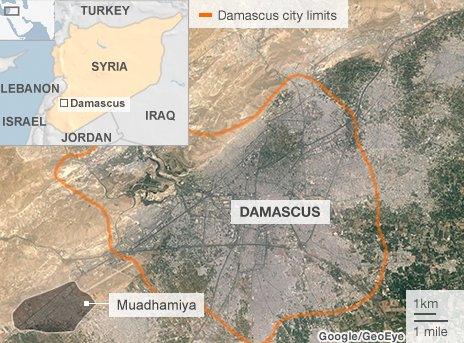

Thousands of civilians were allowed to leave Muadhamiya in October

A new crisis in Syria is looming - starvation. Hundreds of thousands of people living in rebel areas around Damascus and in Homs are under government siege.

This means the electricity has been cut and no food, medicine or gas can enter the town, only bombs rain down. The UN (office for the coordination of Humanitarian Affairs) have expressed grave concern about reports that over half a million people remain trapped in rural Damascus and there are cases of severe malnutrition amongst children.

As one Syrian army officer told the BBC: "They either surrender or starve." So far they are not surrendering.

"Starvation is spreading like cancer," Qusai, a media spokesman in the Damascus suburb of Muadhamiya, told me.

"It's making the townspeople look like ghosts. Personally I've lost over 17 kilos [37lb] in the last four months."

The 28-year-old, who used to work in a five star hotel in the capital, grew up in Muadhamiya, now under siege for over a year.

Matthew Hollingworth, WFP: "These people perhaps a year or two ago would have been living a good life"

In a rare agreement with the government, thousands of civilians were allowed to leave the town in October.

"We didn't see one piece of bread for nine months," one woman told a BBC reporter who was there. People have been reduced to living off olives, leaves, domestic animals and whatever they manage to grow themselves. But despite the hardship, many civilians remained.

"Approximately 8,000 civilians stayed, including about 2,000 women and children," says Qusai (not his real name).

"We've had information that women who were evacuated were sexually harassed and many males over 14 were arrested and are being held at a nearby military base. Some of them may be forced to join the army and fight for President Assad and we heard six men were shot dead. So we don't want to leave."

The reports are impossible to verify because of severe restrictions on foreign journalists in the country.

'No oxygen'

Men and teenage boys were separated upon leaving the village and taken away for questioning, but it is not known whether they are still being held.

Doctors in Muadhamiya say they have to deal with every kind of injury

This fear of persecution was echoed by the resident doctor. "Our identity cards show that we are from Muadhamiya, so we could get arrested at any of the city's checkpoints for coming from a rebel town." Twenty-five-year-old Dr Rasheed (not his real name) was a doctor in the military and now works in the makeshift hospital located in a basement, to protect it against the shelling.

"We only have very simple equipment, but we have to manage every type of injury from the frontline - bullet wounds, lost limbs and worse injuries are typical," he tells me. But despite the bravery and ingenuity of the medical staff, the simple fact is that with medicine and proper equipment they could save more lives.

For Dr Rasheed one day stands out as the worst in the war so far - 21 August, the day of the chemical weapons attack.

"There were 800 injuries. It was such a disaster, but the medical staff were real heroes that day. And many of us were exposed too."

There were so many victims, he tells me, they couldn't all fit in the hospital and had to be treated on the streets outside.

"First we took off their clothes and washed them with water, then used atrophine and another drug, but the big problem was that we didn't have oxygen. I'm sure if we had it, less people would have died."

Such are the horrors that residents are living through. Qusai finds it difficult to believe that it's really happening.

"It's like a terrifying nightmare that just keeps going on and on. You live everyday as if it's your last because you might die any second anywhere.

There are concerns about the fate of many of the men who left Muadhamiya

"I was one of those who got exposed to sarin gas and my heart stopped for a couple of minutes. The doctors thought I was dead and placed me with the deceased for half an hour. If it wasn't for my friend who came and started crying over me I would have been buried alive."

Mother-of-three Umm Jihad (not her real name) has been trying to shield her children - 16-year-old Amjihad, 15-year-old Ahmed and eight-year-old Nesma.

"When I'm with them I always try to make them feel better by saying: 'Alhamdulillah we are doing ok, don't worry things will get better.'

"But when I'm alone I cry, I empty all my sadness on myself. I don't let my children see me like this because I don't want them to lose hope and faith."

She tells me that their symptoms of malnutrition are getting pretty obvious.

"They are getting so skinny and weaker day by day. I've seen my children change so much. They used to talk about school and what they want to do when they grow up. But now all they talk about is the kind of weapons that fall in Muadhamiya."

The townspeople say that what has allowed them to hold out for so long is of course the Free Syrian Army, who manage to steal ammunition and weapons from the army to replenish their supplies.

But it's also the teamwork of the community, sharing food, wood for fuel and encouragement. It's this new spirit which means that even though the price has been so high, they insist they don't regret the revolution.

'True nature'

As a former successful businessman from Muadhamiya, Abu Rajab (not his real name) told me: "We all knew that the price will be so high because we know what our fascist government is capable of.

Through his work he would meet many of the Syrian elite, including members of President Bashar al-Assad's family.

"I saw their true nature," he said. "They acted as if they were Gods and looked down on everyone else as if they were slaves. We did this for freedom. I have no regrets."

Umm Jihad is equally defiant, despite her children's suffering. "I'm going to stay here all the way to the end," she said.

As Qusai says, they weren't asking for a battle. They started by demonstrating peacefully and the government forced them to take up arms after, as he says bitterly, the whole world failed to protect them.

"Bashar al Assad should be taken to the Hague instead of Geneva. It's a big shame. But we are not giving up on our demands. We are not giving up on freedom."

Human Rights Watch has criticised the Syrian government for not allowing access into rebel-held areas, saying the government should "end its humanitarian blackmail , externaland be held accountable for denying aid to civilians trapped in the conflict, a violation of the laws of war."