Yemen's women struggle to reap benefits of Arab Spring

- Published

Women played a prominent role in the demonstrations which helped force Ali Abdullah Saleh from power

The first thing you notice about the Yemeni capital, Sanaa, is how much has not changed.

There are buildings that date back to the 9th Century still buzzing with people and markets all around them.

I was told the market in the old city is called "the moving museum". There is a real sense of history here and it is evident everywhere you go.

Yemen is a very conservative society governed by tribal traditions.

For years, women were almost invisible and had no say in what went on in their country.

'Turning point'

When you take a walk in the streets of Sanaa, the women you see are covered in black from head-to-toe.

That is why the whole world took notice when Yemeni women were at the forefront of the demonstrations that eventually ousted long-time president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, and brought in a new government.

"It was a turning point in my life," says Fayza al-Suleimani.

At first glance it is easy to stereotype Ms Suleimani, who was completely covered except for her eyes.

But, in fact, it was her and thousands of others like her who took to the streets and demanded change.

She did it behind her family's back and had to face their rage when they found out that she was in the streets demonstrating.

"I was also beaten by the security forces in the street," she says.

"This really surprised me. In our culture men don't hit women in public. So when that happened I was shocked.

"The man who got in my car and beat me said: 'Fayza, you'd better stop what you are doing.' But I was more determined than ever."

Gender gap

As I walked with her in Sanaa's Taghyir (Change) Square, which was at the heart of the uprising against Mr Salih, she pointed out where she and other women and men had gathered back in 2011.

Fayza al-Suleimani: 'We made a lot of sacrifices but not for this ending.'

There was pride in her voice when she spoke to me about those days, but also an obvious sense of disappointment.

"We came here and we were full of hope. We made many sacrifices," she says.

"We lost a lot of people. Personally, I lost six friends who died - they were dreaming of a good future for Yemen, for their children and their family and that's not what happened. Nothing has changed," she says.

In fact, things got worse for Yemen after the 2011 uprising.

Unemployment among young people in Yemen is as high as 40%, external, according to the World Bank.

The IMF says nearly half of Yemen's population lives below the poverty line and roughly one-in-two children suffers from malnutrition.

"Life is difficult in Yemen as it is. During transition, life is harder," says Nadia Sakkaf, editor of the Yemen Times newspaper.

Editor-in-chief of Yemen Times, Nadia Sakkaf: "Life is difficult in Yemen as it is - during transition, life is harder than it was"

Conditions are particularly tough for women.

Yemen is the worst country in the world in terms of gender equality, according to a World Economic Forum survey., external

The majority of women are illiterate and more than half get married before the age of 18.

Child brides

Child marriage is one of Yemen's most controversial issues.

"Many girls get married at the age of nine, 10 and 11, when they are very young and can't bear the responsibility of marriage," Horia Mashhour, Yemen's human rights minister, tells me.

"When they are 14 or 15 they can get pregnant and sometimes they die during childbirth."

Um Amna said poverty forced her to sell off her 14-year-old daughter for marriage for just $250 (£150)

Activists said there had been many reports of young girls dying on their wedding night from internal bleeding after intercourse with their husbands. In September, an eight year old allegedly died on the night she wed a man five times her age.

These girls normally come from very poor families. Marrying them off at a young age helps the family financially.

"I don't want to get married. I want to finish school and become a doctor. I don't want to suffer like my sisters," Neema Abdullah tells me.

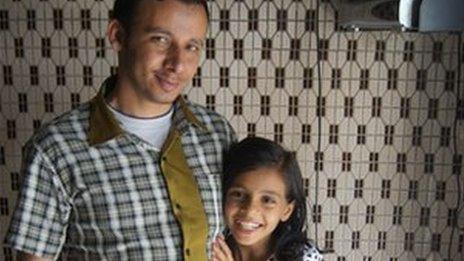

I went to see her and her mother, Um Amna, in their tiny home in a very poor district of Sanaa.

Neema is 14 years old and recently married. She is one of three girls in her family, all married before their 14th birthday. All have been pulled out of school.

Her mother, who has 10 children in total, sat next to her and was very assertive when I asked her why she married off her daughters when they were still so young.

"We needed the money!" she explained. "We had to marry her off to repay our debts. We are very poor and my husband is sick. What do you want him to do? Beg on the street?"

Neema, the youngest, was married off to her cousin because the family owed a rich uncle $250 (£150).

Her other two sisters, 19-year-old Amna and 17-year-old Saada, were also married to settle family debts. Both her sisters are now divorced and came back home after being abused by their husbands.

I asked Neema if she was angry at her parents. She nodded.

"I didn't want to get married and they made me do it anyway.

"They shouldn't have given us away when they knew what would happen to us; that we would suffer," Neema says emphatically.

"Those people who come to marry me or my sisters, they know we are poor. And they know that my parents will not do anything to stop it. And we end up being damaged."

Political will

Part of the reason why women took to the streets in 2011 was to help those like Neema and her sisters; voiceless women who live in poverty and have no access to education.

But in this deeply traditional and tribal country progress is slow.

Ms Mashhour says conservatives are holding back progress on women's rights

"This problem could have been solved quite easily had there been a political will," says Ms Mashhour.

In 2009, Yemen's parliament passed legislation raising the minimum age of marriage to 17. But conservative MPs argued the bill violated Islamic law, and it was never signed.

"There is a very conservative and even extremist group of MPs who make such legislation difficult. It's a small group but they are influential," the minister explains.

These deeply conservative groups are reluctant to see any change in the role of women whether in private or public life in Yemen.

"One time, a member of parliament, who belongs to an Islamist conservative party here, told me: 'Your place is in the house, cooking lunch. That is your role'," Ms Suleimani says. "But I refused. I won't stop."

Ms Suleimani was the first one in her family to finish her education and get a job.

Because of her, many girls in the family have now gone to university and are hoping to work.

"We have to continue fighting to build a future for ourselves in the country," Ms Suleimani insists.

- Published13 February 2024

- Published4 September 2013

- Published26 July 2013