Egyptians fear return to authoritarianism

- Published

There is growing concern about a return to authoritarianism in Egypt, where the military-installed authorities have cracked down on freedom of speech, stifled protests, and arrested activists. Almost three years after the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak, the BBC's Orla Guerin looks at what has become of the revolution.

Ahmad Harara is seldom seen without his Ray-Ban sunglasses. But for the 33-year old former dentist, they are not a style statement.

When he lifts them up, it is to reveal two unseeing eyes - the left one a prosthetic. It bears an inscription - "hurriya", the Arabic word for freedom.

It was the fight for freedom that cost him his sight, one eye at a time.

Mr Harara was shot in the face twice in 2011, both times by police he says.

In spite of his injuries, Ahmad Harara is determined to fight the military's "counter-revolution"

Shot-gun pellets destroyed his right eye on 28 January, a few days after the mass protests against Mr Mubarak began.

He lost his left eye to a sniper that November.

"I am not the person who has paid the highest price," he says over Turkish coffee and cigarette at Cairo's Cafe Riche, where coffee and dissent have brewed for more than a century.

"There are others who had much more serious injuries," he adds, "and they are carrying on."

Military untouched

In spite of his injuries, he too is carrying on.

He is still fighting the regime that plunged him into darkness, which he says has not been overthrown yet.

"The system remains the same," he explains. "The army is maintaining its position. No-one holds it to account. No-one monitors it. On the contrary, it has taken more privileges."

Some say Egypt has returned to the kind of police state which the revolution aimed to remove

"It has ruled here since 1952 and doesn't see the need to change because some young people took to the streets."

Youths are still taking to the streets here, braving tear gas, water cannon and the threat of deadly force, though these days the crowds are much smaller.

A draconian new law has all but banned demonstrations.

Human rights campaigners say it is at attempt to claw back one of the key gains of the revolution - the freedom to speak out.

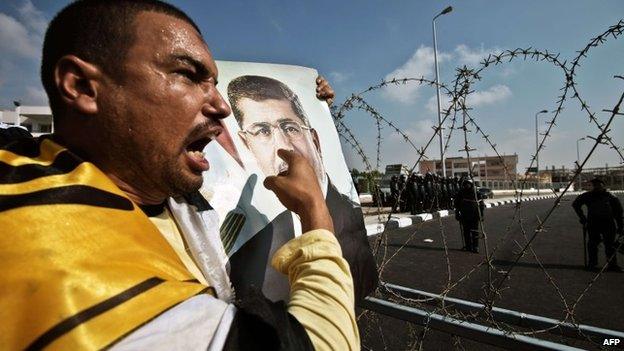

Dozens of liberal activists have been arrested challenging the law, but many believe it is aimed mainly at supporters of the ousted president, Mohammed Morsi, and his Muslim Brotherhood.

Detentions

The revolution brought the Islamist organisation to power, but not for long.

The Brotherhood is now a study in catastrophe, mostly self-inflicted.

The crackdown on the Brotherhood has been portrayed by officials as a struggle against terrorism

Mr Morsi lasted only a year as Egypt's first freely-elected civilian president.

He was removed by the military in July in a popular-backed coup. Though officials still vehemently dispute that definition.

In August, the authorities violently dispersed two pro-Morsi sit-ins, killing hundreds of his supporters.

Since then, thousands more have been detained - including many senior leaders of the Brotherhood.

Brotherhood defiant

So many of the Brothers are behind bars that we turned to some of the Sisters.

We met a trio making house calls in the sprawling Cairo district of Nasr City.

They were led by Wafaa Hefny, a tall and chatty university professor who seemed unfazed by the current crackdown.

Mohammed Morsi is one of thousands of Brotherhood members to have been detained

"I never give up," she said. "I get that from my grandfather."

It was her grandfather, Hassan al-Banna, who founded the Brotherhood in 1928.

Ms Hefny insisted the organisation was at its best in a crisis, and was adapting.

"The upper part, all of it is gone," she said.

"In every district the first level and the second level and some of the third level have gone, but everybody has been upgraded. We don't have any free positions," she added with a laugh.

'Not divided'

We joined her on a visit to a young widow, Alshaimaa Abdallah, whose husband Mahmoud was killed in August during one of the sit-ins.

Ms Abdullah welcomed us, dressed head to toe in black.

She emphasised that her husband was not a member of the Brotherhood, just "a devoted Muslim, defending Islam". But she said she and her family would now be happy to join the Brotherhood.

Alshaimaa Abdallah remains optimistic about Egypt and her children's futures

The articulate former teacher has become a lone parent of three.

Her son Abdul Rahman, who is nearly four, hovered by her chair. He still saves part of every meal for his father, who he thinks is away on a trip.

When I asked what kind of future she saw for Egypt, her response was a surprise.

"I'm really optimistic," she said firmly, insisting that the nation would not be divided.

"It's very hard to separate us. People in every neighbourhood are very close to each other, even if they are different politically."

Cult of Sisi

But a painful, scarring polarisation may be one of the clearest outcomes of the uprising in Egypt.

And it is no surprise that here, in the land of the pharaohs, there is hunger for stability and for a new strong leader.

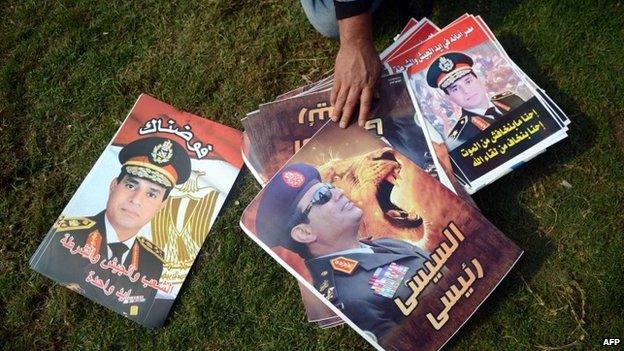

Enter the coup hero, Gen Abdul Fattah al-Sisi - the army chief who removed an elected president and looks set to replace him.

Many Egyptians share the belief that Gen Abdul Fattah al-Sisi averted a civil war

If he runs for president next year - and the latest indications are that he will - the general can expect to win by a landslide.

In Tahrir Square, where crowds overthrew one military ruler, we met a group of demonstrators clamouring for another.

"We love you Sisi," they chanted, in the place where protestors demanded freedom and democracy in 2011.

"He is a crown on the heads of Egyptians," said an elderly man. "He helped us avoid seas of blood."

There are many here who share the belief that the general averted a civil war by removing Mr Morsi.

Such is the cult of Sisi that his face pops up on cooking oil bottles, pyjamas, take-away menus, and sweets.

Trays of Sisi chocolates get pride of place among the cupcakes and macaroons in the Kakao Chocolate Lounge, a cafe popular with diplomats. The owner says the bite-sized Sisis are a bestseller.

Diminishing hope

But for many who fought to end the long reign of Mr Mubarak, all this leaves a very bitter taste.

"The military regime is the counter-revolution," says Mr Harara. "They are still trying to control the country. They cheated us."

There is a real sense here that the revolution is unfinished business.

Protests against the new law on public gatherings are continuing despite dozens of arrests

Though two presidents have been removed in three years, the old order has not been completely swept away.

The army remains the real power here, and much of the hope for a new Egypt has been erased.

The country is not much different from before the revolution, according to Tamara Alrifai of Human Rights Watch.

"Freedom of expression seems worse than before 2011," she says.

"There's very little space for opposition media, and there is a campaign of arrests and disappearances of anyone who dares to defy the current climate. It's disappointing to see that we are almost back where we started three years ago."

'Another Mubarak'

Elections are coming to the most populous Arab nation.

Next year Egyptians will vote for a new constitution, president and parliament.

That may look like progress towards democracy, but experts warn it may be anything but.

"Sisi controls the police, the army, the judiciary and the media," a seasoned Cairo analyst told me.

"He is popular and he will get votes," she said. "The fear is that once he is in power, he will never be out. He could be another Mubarak."