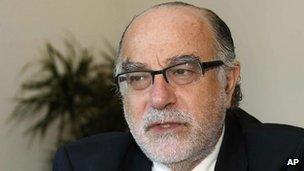

Mohamad Chatah killing targets potential Lebanon PM

- Published

The blast deprived Lebanon's Sunni opposition of a potential leader

With every assassination in Lebanon, and there have been too many, the list of possible culprits in the minds of the Lebanese is usually limited to two possibilities, determined by your political leanings: Syria or Israel and their respective allies in the country.

The search for possible motives is more intricate and the key question is usually: what is the message? Often it is simply meant to terrorise, and break the will of one political side or the other. At other times, the goal is to deprive the leadership ranks of a political grouping of its key and most promising figures.

With the assassination of former finance minister Mohamad Chatah, the goal appears to have been both: cow his allies and deprive them of a potential leader at a time when Lebanon is deeply divided about the war raging next door in Syria.

Mr Chatah, a Sunni, was a key adviser of former Prime Minister Saad Hariri. Both opposed Syria's President Bashar al-Assad and Hezbollah, the Shia militant group that has been sending fighters across the border to support Mr Assad for months.

There are rarely definitive versions of "who and why" to explain Lebanon's long list of unresolved assassinations.

But in conversations with various players in Lebanon, a picture emerged of a man who was clearly the brain of the Sunni opposition, quietly preparing for a possible bigger role in Lebanon, and was working to convince the international community to support his country's neutrality in the Syrian conflict.

Polarised

Two political sources in Lebanon confirmed that Mr Chatah's allies were floating his name as a possible choice for prime minister.

Lebanon has been without a cabinet for nine months. The current prime minister-designate could give up his efforts soon.

The move would require the support of Lebanon's Christian president Michel Suleiman. He is likely to have agreed, although there is no certainty a new cabinet would have been formed successfully.

Mr Chatah, a soft-spoken moderate and former finance minister who kept mostly a low profile, seemed an unlikely contender.

Lebanon's prime minister is always a Sunni, and a Western diplomat said that any credible Sunni politician is a candidate.

But in a country that is deeply polarised, mostly along sectarian lines, about its long history and ties with Syria, few Sunni politicians have enough street-cred in their own community and can also get the backing of Hezbollah and the pro-Assad camp.

Although the Shia group would likely have rejected Mr Chatah as well, it's possible that his political bloc and that of Mr Suleiman could have joined forces to corral enough support, in a desire to extricate the country from its current morass. But there was nothing imminent about such a move.

Either way, Mr Chatah's killing deprives his political camp of a key strategist and possibly of the only Sunni politician it could have put forward for the position in the current context. It also sends a powerful, bloody message to Mr Hariri and the anti-Assad camp in Lebanon.

Voice of moderation

Mr Chatah was one of those arguing for a separate meeting on Lebanon at the Geneva talks on Syria proposed for January

Lebanon could soon face an unprecedented constitutional vacuum. Parliament's term expired in the summer and the president's mandate runs out in May.

Mr Suleiman is also a big proponent of Lebanon's neutrality in the Syria conflict and has been surprisingly open in his criticism of Hezbollah. In a recent BBC interview, he called on the group to withdraw from Syria.

Mr Chatah was a voice of moderation, a former ambassador to the US who still had good connections in Washington DC. He was also advisor to Saad Hariri's father, Rafik, who was killed in 2005 in a massive car bomb, a few hundred metres away from the spot where Mr Chatah was targeted.

Saad Hariri indirectly accused Syria and Hezbollah of being behind the killing.

"Those who assassinated Mohamad Chatah are the ones who assassinated Rafik Hariri; they are the ones who want to assassinate Lebanon," he said.

Syria denied any involvement while Hezbollah condemned the killing as a heinous crime but without making any accusations. On this occasion, no one pointed the finger at Israel, not even for posturing.

Lebanon's usual complex politics have been compounded by the war in Syria. All its current crises are connected, directly or indirectly, to the conflict next door.

Syria's allies in Lebanon, like Hezbollah, are demanding a large share of the cabinet seats, while Saudi Arabia, which supports Mr Hariri and opposes Mr Assad, is pushing back against the formation of a cabinet that would include Hezbollah, while the group is fighting to support the Syrian president.

About half an hour before his death, Mr Chatah tweeted that ''Hezbollah is pressing hard to be granted similar powers in security and foreign policy matters that Syria exercised in Lebanon for 15 years".

Mr Chatah's friend and ally, Lebanese legislator Bassem el-Shabb also said the former ambassador to the US was working hard to convince the international community to support Lebanon's neutrality in the Syrian conflict.

Violent reminder

The killing of Hezbollah senior commander Hassan Lakkis was blamed on both Israel and Syrian rebel groups

Efforts are under way to hold a peace conference on Syria in Switzerland at the end of January. Mr Chatah was one of many politicians proposing to hold a separate meeting on Lebanon that would include an agreement for Hezbollah's withdrawal from the fighting in Syria.

Mr Chatah had penned a candid open letter, external to Iran's President Hassan Rouhani along those lines, appealing for the withdrawal of all Lebanese parties including Hezbollah from the fighting in Syria.

Mr Chatah died before he could gather signatures from Lebanon's legislators.

The Western diplomat said that Mr Chatah remained realistic, however, about the chances of getting Saudi Arabia and Iran, Hezbollah's other ally, to sit down at the table.

Hezbollah has also paid the price of its involvement in Syria. In recent weeks, suicide bombings have targeted civilians areas of its stronghold in the southern suburbs of Beirut. When one of its operatives was killed, the finger was pointed at both Israel and Syrian rebel groups settling scores with Hezbollah.

Lebanon is still haunted by a long string of unresolved post-civil war assassinations stretching back to 2005, with the massive bomb that killed Rafik Hariri. An international tribunal investigating the killing has indicted several Hezbollah members and implicated Syria. The trials are set to start in mid-January in The Hague.

Most of those assassinations took place before the conflict in Syria started in 2011 and decimated the ranks of the anti-Syrian political camp.

Mr Chatah's killing appears to be both a continuation of that trend and a violent reminder that Lebanon's fate is now inextricably tied to the outcome of the war in Syria.

You can follow Kim on Twitter, external

- Published27 December 2013

- Published20 December 2013

- Published14 July 2013

- Published27 June 2013