Analysis: Anbar violence goes beyond sectarian conflict in Iraq

- Published

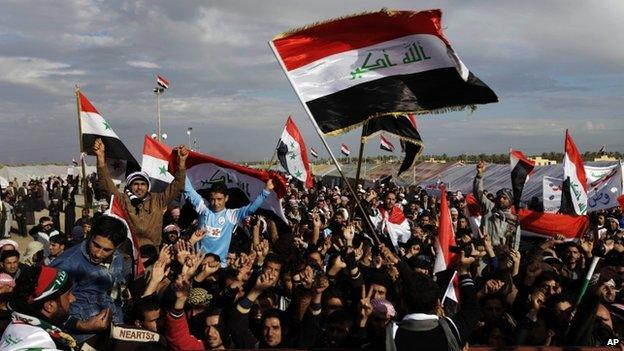

Police and pro-government tribesmen have been battling ISIS and its allies for control of Ramadi and Falluja

The attacks on the main police station in Falluja on Wednesday, followed by the takeover of other police stations there and Ramadi on the following day, are part of the escalation in the Sunni-Shia sectarian conflict that has long plagued Iraq and reached its worst point in 2006-2007.

But the violence is also part of the broader malaise affecting all Iraqi provinces, including some of the major Shia ones, as Prime Minister Nouri Maliki seeks to tighten his own political control and power, and in the process to impose a highly centralised system of control, which most provinces are beginning to resent.

At present, at least one-third of Iraqi provinces are seeking to transform themselves into regions enjoying the same degree of autonomy Kurdistan has already achieved.

The confrontation in Anbar was precipitated by Mr Maliki's decision on 30 December to dismantle with force a protest camp that had existed in Ramadi for over a year.

The camp had been set up to challenge what many Sunnis see as their systematic marginalisation by Baghdad, and the repression of prominent Sunni politicians.

The protest camp was not an al-Qaeda operation, but Mr Maliki's move triggered a strong response by the militants of the al-Qaeda affiliated Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (Isis).

Vying for dominance

Reports from Anbar province are confusing at present, but seem to indicate that parts of Falluja and Ramadi are in the hands of Isis, while tribal militias control other areas.

The anti-government protest camp in Ramadi was set up after demonstrations broke out in late 2012

The confrontation has been long in the making.

Since the US withdrawal, al-Qaeda-aligned groups started reorganising and the number of terrorist attacks, including in Baghdad, increased again.

The militancy of Sunni organisations escalated further after the onset of the conflict in Syria, where the Syrian-based Jabhat al-Nusra and the Iraqi-dominated Isis have established themselves as the most effective anti-Assad fighting forces and are vying with each other for dominance.

Extremist organisations have found a ready audience in Iraq, where Mr Maliki's policies continue to alienate the Sunni population.

Sunnis, who consider themselves the true Iraqis and still have trouble accepting the indisputable fact that they constitute a statistical minority in the country, would be difficult for any Iraqi government to appease.

Mr Maliki has worsened the situation by allowing and encouraging purges of Iraqi politicians in the name of de-Baathification and largely discontinuing the US-initiated policy of working with Sunni tribal leaders and their militias - the so-called Sons of Iraq - to isolate al-Qaeda.

He has systematically marginalised prominent Sunni politicians such as former Vice-President Tariq al-Hashemi and former Finance Minister Rafi al-Issawi. The latest example is the arrest last week of Sunni MP Ahmed al-Alwani, who had been negotiating between the government and the protesters.

Fight for it

Mr Maliki is unlikely to succeed in re-establishing full control in Anbar by force alone.

He does not have the capacity for a military surge such as the one that allowed the United States to prevail in 2008, nor has he shown the political flexibility to make deals with the tribal leaders and their militias, as the United States did.

Ahmed al-Alwani is a prominent supporter of anti-government protesters

Yet he needs to find a political solution, not only in Anbar, but in other provinces chafing under the control of Baghdad.

Since 2009, Iraqi provinces have elected provincial councils and governors, but in reality enjoy little self-government.

Although each province is entitled to a share of the country's total revenue based on the size of its population, much of the money is channelled through the ministries in Baghdad.

Even money that should be spent at the provincial level tends to remain in Baghdad, and provinces have to fight for it.

Crucial battle

The result is not only anger on the part of the councils, but also a severe underspending of the budget in most provinces. Coupled with lack of security, this situation has resulted in a painfully slow reconstruction effort, even as oil revenue increases.

At least six provincial councils as a result have sought at various times to initiate the process of transforming themselves into regions with the same autonomy as Kurdistan.

The transformation is allowed by the constitution, but Baghdad has blocked all attempts. It may not be able to continue doing so for much longer.

The parliamentary elections scheduled for April will be a crucial battle between those embracing Mr Maliki's vision of a centralised Iraq and the growing number of both Sunnis and Shias who are beginning to look at the autonomy of Kurdistan as an example to be emulated.

The battle raging in Anbar is thus more than a sectarian confrontation between a Shia-dominated government and the Sunni population of the region. It is more than a battle between al-Qaeda and the Iraqi military and police. It could also be the first salvo in an Iraq-wide battle for regional autonomy.