Protests throw spotlight on Israel's African migrant pressures

- Published

Richard Galpin reports from the US embassy where many migrants have gathered

Hundreds of African women and children marched across the Israeli city of Tel Aviv on Wednesday to demonstrate outside the offices of the United Nations and the embassy of the United States.

It was the latest in an unprecedented wave of protests by African asylum seekers, who fear the Israeli government is trying to force them out of the country.

Since a new law came into force last month, the asylum seekers - most of whom are from Sudan and Eritrea - say the authorities have been instructing many of them to leave the cities and towns where they have been living and report to a detention centre in the Negev desert in southern Israel.

The new law gives the authorities the power to hold them in the centre indefinitely, putting them under intense pressure to agree to leave Israel voluntarily.

The African immigrants began arriving in Israel in 2006 and it is estimated there are currently 53,000 in the country.

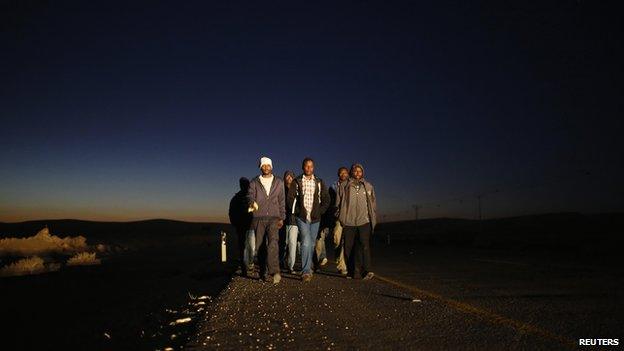

Thousands of African migrants have held protest marches over the past week

'Seeking protection'

"The reason I am here is because I fled violence and persecution back home, the on-going genocide," says Dahar Adam who is from the Darfur region of Sudan.

"I came here seeking protection as a refugee and have been here almost seven years, but I didn't get any kind of status or recognition as a refugee."

"We requested many times, but they denied and neglected us, they don't want to take this problem seriously," he said.

In a rare public rebuke, the UN Refugee Agency has accused the Israeli government of following a policy that "creates fear and chaos amongst asylum seekers," and warned that putting asylum seekers under pressure to return home, without first considering why they had fled, could amount to a violation of the 1951 Refugee Convention.

Israel says most of the migrants do not meet the criteria for refugee status according to international convention

'Economic migrants'

But the government is sticking to its position that the African immigrants are not refugees but are instead economic migrants who see Israel as an attractive destination because it is the nearest developed country where they can find jobs.

The government also insists it has the systems in place to process any asylum applications.

"Only a few hundred have applied," says the foreign ministry spokesman, Yigal Palmor.

"It is quite a mystery why not more have tried to use the procedure."

And only a handful so far, approximately a dozen, have been granted refugee status.

"The others have been found to be working migrants or other types of migrants and did not qualify for refugee status under the criteria of the Refugee Convention," Mr Palmor said.

Hundreds of migrants are being held in a detention centre in the Negev desert

But a spokesperson for the UN refugee agency rejected this, telling the BBC that the Israeli government, having initially advised the immigrants they did not need to apply for asylum, then changed its mind in 2012.

But, the UN spokesperson said, the government failed to inform the migrants that they needed to submit their applications.

Five to a room

.jpg)

Zena, from Eritrea, has a job and says he lives in better conditions than African friends of his

Many of the Africans live in a run-down area of south Tel Aviv, attracted to the city by the chance of finding work in the many restaurants, cafes and hotels.

At the entrance to a dingy, dilapidated apartment block, I met Zena Mebrahtu, a 27-year-old Eritrean, who invited me to follow him up the stairs to see the room that is now his home.

He shares the bed and single electric cooking ring with his younger brother.

The other rooms which make up what was once an apartment, have all been rented out individually to Sudanese and Eritrean immigrants.

But Zena knows he is lucky. He has a fridge, a television and even a surfboard leaning against the wall, given to him by a friend.

"I have a good job," he says, "I have Israeli friends and they gave me a job."

"My [African] friends are living in the worst condition, in a room like this with five people."

Zena's neighbourhood has a particularly high concentration of immigrants, and relations with the local Israeli population are tense.

"There are people who behave well with me," he says.

"But there are more who don't like me, don't like refugees and don't like me staying here.

"They say to me you are dirty, you don't know how to live, you need to go home.

"Most of them think I came to Israel to get money."

Illegal migrants who agree to leave the country get $3,500 compensation

On the street outside, a local Israeli man Yaniv Avigad poured out his feelings about the immigrants.

"They are destroying our lives in many ways," he said.

"There's a lot of violence. I have lived in the neighbourhood ever since I was a little kid and they always said this was a bad neighbourhood.

"But I've never encountered anything like it since they came here five years ago."

"I feel very scared, it is not my country any more, it is theirs."

Mr Avigad believes the government is not being tough enough and wants new laws which will stop the African immigrants renting rooms.

"I think then they will go home."

The Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has warned the immigrants that their protests will make no difference to the government's policy of removing "illegal infiltrators".

The increasingly shrill debate about the African immigrants prompted President Shimon Peres to speak out last week.

He reminded Israelis that the country had signed the UN convention on refugees and this prohibited the deportation of people to countries where their lives would be in danger.

He added: "We remember what it means to be refugees and strangers."

And all this even though the government says it has successfully stopped almost all illegal immigration into Israel, with the completion last year of a fence across the border with Egypt - the route which the Sudanese, Eritreans and other Africans had been using.

- Published5 January 2014

- Published6 January 2014

- Published6 January 2014

- Published25 May 2012

- Published6 September 2012