Homs evacuees: Anxious young men from a besieged Old City

- Published

The BBC's Lyse Doucet speaks to men who are being held in the centre in Homs

We didn't recognize the men we'd met just a few days earlier when they emerged from the rebel-held Old Quarter of Homs.

Their ragged beards are trimmed or shaved. They have new clean clothes.

But they still wear the hunted look of anxious men as they wait for their cases to be decided in the city's al-Andalus school that is now both shelter and screening centre.

And the memory of the painful life they escaped in the besieged Old City still haunts them.

"Families were ready to kill for food," Youssef tells us, as nine-year-old Mariam throws all the loving weight of her little arm around her big brother. He's now been re-united with family members who are able to visit him here.

"People started eating grass and cats. There was no medical care, no water from the wells, no electricity."

He shakes his head as he draws a long pensive breath on a cigarette.

Many of the men have lost limbs

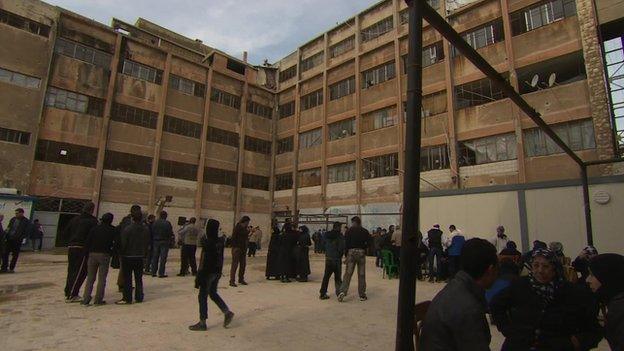

We were given permission from the governor's office to visit this school, which is now under armed guard. About 300 men are still being held for questioning here after they fled the ruins of the Old City during a UN-backed "humanitarian pause" which came into force more than a week ago.

On a warm winter's day, many of the men sit or stroll in the open courtyard, or huddle with family visitors, sharing coffee and conversation.

The scene appears relaxed and informal. But there's a pervasive undercurrent of tension.

We meet Youssef and about a dozen other men in the first classroom we enter.

It's called Room One. But the men lying under grey blankets stamped with a blue UN logo feel they've reached rock bottom.

The men are being held at this former school in Homs

They're all disabled, many with double amputations.

"There are about 200 more people still trapped in the Old City who have no legs," calls out one young man from the far corner of the room. "They can't move."

Neither can he.

No doctors

Another young man, a 21-year-old who wears his sadness on a bright handsome face, says he stopped fighting with the Free Syrian Army (FSA) after he took five bullets in his leg.

"There were no trained doctors or the right medicine to amputate my leg," he explains. "They gave us painkillers but it was very painful."

Now he just wants to join his sister and fix his leg, as well as his life.

These men came out through the UN-brokered deal with the warring parties, even though the agreement only focused on women, children, and the elderly.

Fourteen-year-old Abdul says he has no one in the world, after his mother died of malnutrition

The men were warned they would face questioning, and if their names were on a wanted list, possible trial.

But there are no good choices in a very bad situation.

Many express the same sentiment: if they stayed inside, they faced certain death - better to take a chance during a rare ceasefire.

"We faced death inside the Old City and are ready to face death outside," asserts one man who, like many in the school, did not want his face or name to appear on camera.

But he wanted to share his story.

He tells us he came out with the group which fled on the first day of the truce, on Friday 7 February. One hundred and eleven of those men were soon freed.

"Are they going to take us to prison or release us?" he asks rhetorically.

"Our future is mysterious and that makes us fearful," he adds nervously.

'Hope'

Another man who came out on the third day of the evacuation says news of the first releases had given him hope.

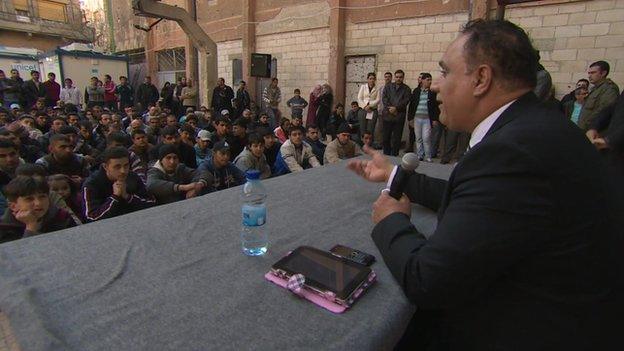

When the Governor of Homs, Talal al-Barazi, sweeps into the school with his entourage, I ask him what will happen to the men.

"I believe most of the men will be cleared or be given an amnesty," he declares.

"They will be free to go wherever they wish. For those who are not, they will be tried in civilian courts."

Then he quickly steps outside, grabs a microphone, and takes a seat at a wooden table to address the large crowd of men now seated cross-legged in the courtyard.

The men were gathered in the courtyard to listen to the governor

"We are all on the same side; we are all Syrian," he tells them in an impassioned speech rooted in his conviction that the road to peace goes through country, God, and President Bashar al-Assad.

'Re-education'

The governor has made this operation in the Old City his personal mission. He's been a constant presence, at all hours, throughout the evacuation. Said to be backed by the president himself, he's reportedly stood up to groups like the pro-government paramilitary National Defence Force, whose members are known to have attacked the aid convoys they see as freeing and feeding their enemy.

The man who runs the facility is, literally, the face of this war. A bullet pierced his cheek during the ferocious battles in the Homs neighbourhood of Babr Amr.

With a sunken cheek, and twisted mouth, he presides with a forceful presence over daily "re-education" classes on everything from religion to reconciliation. On the day we visit, he's flanked by white turbaned mullahs who've come to instruct the men about the true meaning and mission of Islam.

The governor of Homs has been determined to make the evacuation happen

When he takes the microphone, his speech is peppered with both wit and warnings as he urges the fighters not to take up arms again.

A few young men in the front row clap with approval; those further back stand stone-faced, arms crossed.

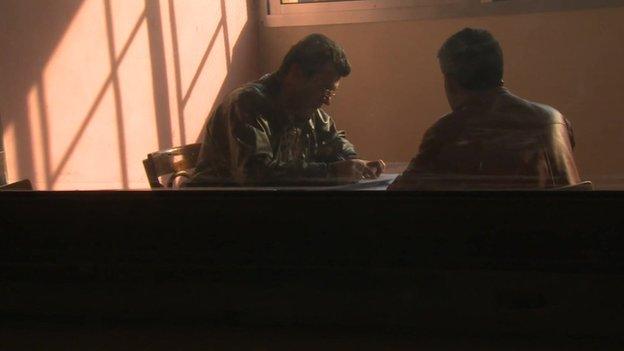

On the top floor of the school, we walk down the hallway where wooden desks are piled high. Through glass windows of empty classrooms, we can see men being questioned.

Several tell us, off camera, that the interrogations involving police and the intelligence services also focus on gathering information on the rebel fighters still in the Old City, including the top commanders.

The interrogations are taking place inside empty classrooms

It's another reason why many are uneasy about what was billed as a "humanitarian pause".

The International Committee of the Red Cross has publicly criticised a deal which did not include a "firm commitment from all sides to respect the basic principles of international humanitarian law".

UN officials are present at the al-Andalus school throughout the day, and also visit at night. They've done spot checks on people who've been released. It's clear their presence, including some difficult conversations, is making a difference.

"The government wants to make a good example of this case," the UN's Resident Humanitarian Coordinator Yacoub el Hillo told me. "We are hoping they will live up to their commitment."

The al-Andalus school is a world away from Syria's notorious detention centres. But there are growing concerns about this process, including questions about the exact "charges" men will face.

We're told by some men that lower-ranking officials threatened them with harsher action once the "people with blue helmets" leave.

Both the UN and the governor say they're not leaving.

But most of the men still aren't sure when they will get out of here, and where they will be free to go.

The evacuees say they faced certain death if they remained in the besieged areas