Pessimism pervades Iran nuclear deal talks

- Published

Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif believes a long-term agreement is possible

Now the difficult part begins.

Back in November, the P5+1 - China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States - reached a deal with Iran that cleared the way for talks on the future of its nuclear programme.

The interim deal is far from perfect, according to many nuclear experts.

There is no halt for example to Iran's uranium enrichment activities, a long-time demand of the United Nations Security Council.

Nonetheless, the interim deal constrains Iran's nuclear activities and provides better access for inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), in return for limited sanctions relief.

In essence, it bought time - six months - for substantive talks to get under way. Those talks began on Tuesday in Vienna.

Having got to this point at all is progress. But there is little optimism on either side that the talks will succeed.

Mutual suspicion remains great and there is still a fundamental uncertainty as to what Iran really wants.

Is it prepared to reduce its nuclear programme to a minimum to lift sanctions, get its economy back on track and become a more "normal" player in world affairs?

Or is it seeking to achieve a loosening of sanctions while retaining the status of a threshold nuclear state, ie one that has the capability to move towards developing a nuclear bomb reasonably quickly at a time of its own choosing?

Several key problems must be resolved if there is to be a long-term deal.

These are complex technical matters, coloured in many cases by political factors and considerations of national prestige.

Rolling back enrichment capability

Last month, Iranian scientists halted all enrichment of uranium to 20%

Iran is widely believed to have the technical knowledge to build a nuclear bomb. That simply cannot be unlearnt.

The ideal, in Western terms, would be for Iran to halt uranium enrichment altogether.

This is for example what Israel - which is clearly not a party to the talks - is insisting upon.

But few experts that I have spoken to believe that such a halt is a realistic possibility.

The goal of any long-term deal, they believe, is to establish a level of enrichment commensurate with Iran's practical needs and a level of oversight that enlarges the "break-out time" to be sure that any future Iranian move towards a nuclear weapon would be spotted as early as possible.

Prior to the interim deal, this break-out time was probably as little as six weeks.

By this summer, with the dilution and conversion of stocks of Iran's most highly-enriched uranium, it should be significantly longer.

The goal will be to reduce the scale and scope of Iran's enrichment operation, by reducing the number of centrifuges to ensure that the break-out time is as long as possible - perhaps up to a year.

The West would also like to see constraints on centrifuge research and it remains concerned about buried enrichment facilities like that at Fordo, and indeed the possibility that there could be other such sites that have so far not been revealed.

The Arak reactor

Iran has committed not to commission or fuel the Arak heavy-water reactor during the interim period

Iran's heavy-water reactor under construction at Arak is another concern.

This, once operational, would provide the Iranians with plutonium, giving them a second potential route towards a nuclear weapon.

Iran says that it has no intention of building a reprocessing facility that would be needed to extract the material from irradiated fuel, but Arak remains a long-term proliferation concern.

The West might prefer Arak closed or replaced by a light-water reactor that is less of a proliferation problem.

Alternatively, spent fuel might be removed to another country.

Iranian officials have talked of making unspecified modifications to the plant.

But as with any agreed level of enrichment, much more intrusive monitoring provisions are going to be needed.

Iran's past activities

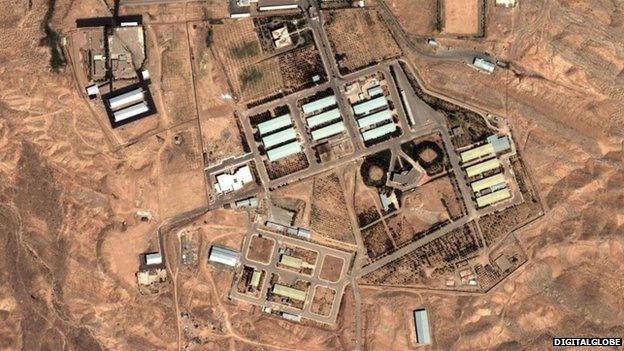

The IAEA suspects activities "relevant to the development of a nuclear explosive device" occurred at Parchin

The body that would be responsible for such monitoring is the IAEA.

It already has longstanding concerns about Iran's past research activities, some of which appear to be military-related.

It is pursuing a parallel set of talks with the Iranians to try to clarify what went on.

These issues will also have an important bearing upon the wider progress of the talks on Iran's nuclear future.

Given the complexity of these issues, speedy progress is unlikely.

There is provision in the interim deal for it to be extended for a further six months, and indeed beyond this if necessary.

Many experts believe that even at this early stage, such an extension is likely and the talks could go on for at least a year.

It is clearly possible to see a win-win situation where Iran retains its peaceful nuclear programme and the international community emerges confident that an Iranian bomb has been forestalled.

But much depends upon Iran's willingness to play ball.

These talks do not take place in a political vacuum.

Iran has a number of "red lines", including not dismantling any facilities such as Fordo

Outside factors could influence progress, potentially throwing things off-course.

Major commercial deals with Iran that threaten to undermine remaining sanctions, for example, could encourage the US Congress to bolster future sanctions, which in turn might provoke a very negative reaction in Tehran. Iran's role in the Syria crisis could provoke tensions - and so on.

The stakes though are very high.

Not so long ago there was talk of Israeli military action against Iran, largely discounted by many experts as just that - talk to galvanise Western opinion.

But if the most serious diplomatic effort so far to resolve the tensions over Iran's nuclear activities was to fail, military action could then be back on the table.

And the consequences of that could be disruptive and unpredictable.

- Published22 January 2014

- Published20 January 2014