The deep discord bedevilling the Arab world

- Published

Members of the Arab League have struggled to find a common direction for decades

The world has learned to expect rhetoric aplenty, but little of substance from Arab summits - and the one scheduled for Kuwait on 25-26 March will be no exception.

Indeed, expectations are, if anything, even lower than in the past.

This latest heads-of-state meeting, like all previous ones, is being convened by the Arab League, which was established nearly 70 years ago to foster mutual co-ordination in order to achieve "the close co-operation of the member-states".

In the euphoria of that post-colonial independence era much more than co-operation seemed possible.

Millions of Arabs dreamed of smashing down the border fences erected by the British and French colonists to achieve unity from Morocco in the west to the Gulf states in the east.

All the ingredients seemed to be there as energetic young leaders took power: shared religion, language, history and culture - and a craving for a return of Arab self-esteem.

But surely today it can be no more than a handful of starry-eyed idealists who still cling to the dream of Arab unity.

Half a century or more of inter-government jealousy, rivalry and war have long buried that dream in the minds of most Arabs.

The start of the popular uprisings in 2011 - the Arab spring - raised expectations again, not of Arab unity, but of something that would still come close to meeting popular aspirations.

The overpowering urge to remove dictators from power was driven to a large extent by that same desire for dignity and self-esteem.

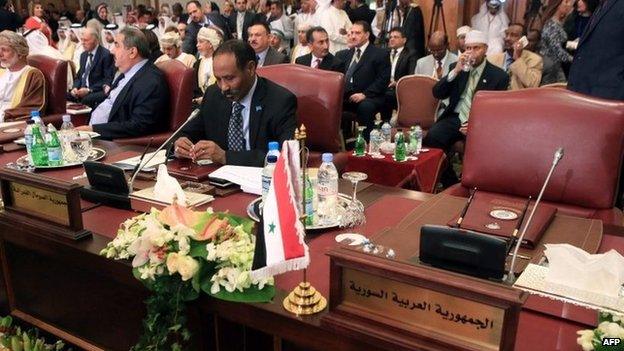

The Arab uprisings of recent years have not been the unifying force that many had hoped

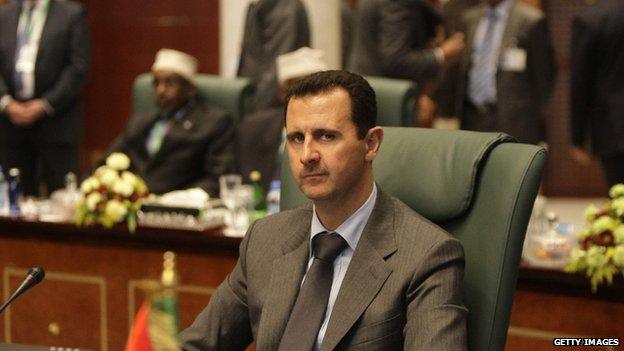

The Syrian conflict has exacerbated divisions among Arab states

The new regimes, it was recognised, would not break down the colonial borders, it was too late for that.

But the hope was that they would at least work together in the common cause of facing shared regional challenges: Israel, the plight of Palestinians, inequality in wealth distribution, youth unemployment, failing education systems, paltry intra-Arab investment, and so on.

Once again, reality has fallen woefully below even the most modest expectations.

In four decades of covering the Middle East I cannot remember the Arab world being as multilaterally fractured as it is today. Arabs are trapped under a dense and complex cat's cradle of ideological and sectarian differences.

Even in the one corner of the Middle East where there is a regional body, the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC - comprising Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates), there are fresh challenges.

Formed in 1981 as Britain withdrew from the Gulf, the GCC has failed to achieve its most ambitious targets of economic integration and the establishment of a credible joint defence capability. But today it faces unprecedented discord:

Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain have withdrawn ambassadors from Qatar because of the latter's support for the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) in Egypt and elsewhere.

Kuwait and Oman have remained neutral in this dispute, so there are now three clearly different camps within the GCC on regional policy and support for the MB.

Saudi Arabia and Bahrain accuse Iran of meddling in their internal affairs by stoking unrest within their Shia communities, while Oman has recently hosted the Iranian foreign minister on an official visit. Oman also angered other GCC states by brokering secret talks between Iran and the United States on the nuclear issue.

Further afield, the list continues:

Iraq has accused Saudi Arabia and Qatar of seeking to destabilise the country.

Relations between Egypt and Qatar are strained over the MB issue.

Saudi Arabia has designated the MB a terrorist group.

Egypt has designated Hamas a terrorist group and is keeping Gaza isolated.

Syria, embroiled in a civil war with outside backing, has accused Saudi Arabia and Qatar of seeking to undermine the country.

Saudi Arabia and Qatar are supporting different factions of the Syrian opposition.

The Arab Gulf states, Egypt and Jordan accuse Iraq of acting as an agent of Shia Iran and allowing Iranian arms to reach Syria - and of marginalising the Iraqi Sunni community.

Lebanon is divided between those for and against the Syrian government, and for and against Hezbollah's military support for Damascus.

Against this background it will be surprising if many Arab heads of state feel enthusiastic about attending the next summit in Kuwait (Syria is already suspended from the Arab League). An agenda that took into account even a fraction of the above grievances is unimaginable.

Unity has been off the table for many years. Today, meaningful intra-regional co-operation, too, is looking like a distant prospect.

This leaves individual Arab states to cope alone as best they can with the range of challenges facing the Middle East - that is when the regimes are not preoccupied with fighting for their interests in the maelstrom of regional disputes.

- Published5 March 2014

- Published12 December 2013

- Published13 January 2014

- Published1 July 2013

- Published24 August 2017