Razed mosque symbol of divided Bahrain

- Published

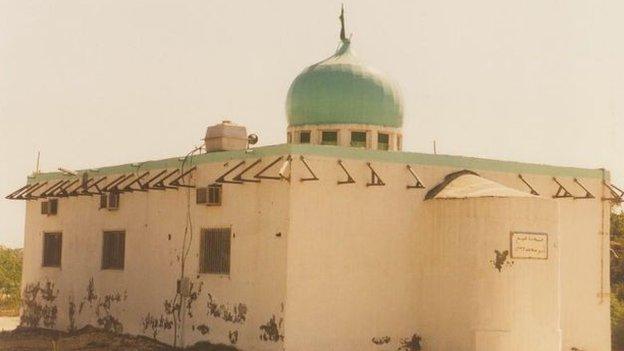

The government argues that the Barbagi Mosque encroached on a safety lane and was a hazard to traffic

When an historic Shia Muslim mosque in Bahrain was bulldozed on 17 April 2011 on the orders of the government, it sent shockwaves through the island's majority Shia community.

The Amir Mohammed Mohammed Barbagi Mosque was more than 400 years old. It had a prominent location on Sheikh Salman Highway, which leads to a causeway linking Bahrain to Saudi Arabia.

The mosque was one of at least 30 religious sites, all of them Shia, which were destroyed over a two-month period at the height of anti-government uprising three years ago.

The related unrest left dozens of people dead, hundreds injured, thousands in prison and thousands more without jobs, most of them Shia.

'Violating laws'

In March 2011, troops from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) states had rolled down Sheikh Salman Highway and past the Barbagi Mosque to help the Sunni ruling family, the Al Khalifa, to restore order and crush the dissent.

It was after that intervention that the destruction of mosques began.

The Shia community wants the mosque to be rebuilt in its original location, but the government disagrees

King Hamad put a halt to further demolitions in May 2011, a few days after US President Barack Obama publically rebuked the Bahraini authorities for using "brute force" to quell "legitimate calls for reform", warning: "Shia must never have their mosques destroyed in Bahrain."

The government had justified the demolitions by saying the religious sites were violating zoning, land-use and planning laws.

It also alleged that they were being used to store weapons, a charge for which little or no evidence was provided.

A panel of independent human rights experts was subsequently tasked by the king to examine human rights abuses.

An investigation of the destruction of religious sites was part of the remit of the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI).

"The government must have been aware of the construction of these structures and that they lacked proper legal permits and did not conform to building regulations," the BICI's report noted, external. "Nonetheless, the government had not stopped the construction of these structures nor taken action to remove them for a number of years."

"The government should have realised that under the circumstances, in particular the timing, the manner in which demolitions were conducted and the fact that these were primarily Shia religious structures, the demolitions would be perceived as a collective punishment."

The report was critical of the manner of the demolitions.

"General Security and/or riot police forbade the locals from removing Korans and other religious artefacts from the places of worship," it said.

In response the government promised to rebuild the religious sites. To date, according to a report sent to the BBC, external, 10 of the 30 demolished have been rebuilt, while 17 others are under construction.

"Procedures to regularise the status and location of the remaining three to comply with land use and planning laws are under way," it adds.

Relocation

Sheikh Maytham al-Salman, a spokesman for the Bahrain Interfaith Centre and a prominent critic of the government, told the BBC the demolitions were "not only a crime but cultural genocide".

"It was collective punishment - a way for the government to show it was willing to go to any lengths to stop the demands for a democratic transition in Bahrain," he said.

Shia leaders blamed Bahrain's Justice and Islamic Affairs minister for the demolitions

Sheikh Salman added that he believed that Bahrain's Justice and Islamic Affairs Minister, Sheikh Khalid bin Ali Al Khalifa, bore "a huge responsibility" for the destruction of the mosques.

"We believe he gave the implementation order for the demolitions. He is the minister responsible for Islamic affairs. This could not have happened without him being involved," he explained.

Officials did not respond to a request from the BBC for a comment from the minister.

The Barbagi Mosque has yet to be rebuilt. But worshippers pray on the site where the mosque once stood.

Their presence serves as both a silent protest and a reminder to all who drive along the Sheikh Salman Highway of what happened there three years ago.

The Shia community is insisting that the mosque be rebuilt in its original location. However, the government wants to move it away from the road.

Shia have continued to pray at the former site of the Barbagi mosque, beside the Sheikh Salman Highway

Opponents say that is because a Shia mosque in such a prominent location on a road much frequented by members of the ruling family and Saudis visiting Bahrain is an annoyance.

For its part, the government argues that the mosque had encroached on a safety lane and was a hazard to traffic.

But for many Shia, the destruction of the Barbagi Mosque remains a potent symbol of everything that is wrong with the government's treatment of their community.

Sheikh Salman says: "There is pain in the hearts of thousands of Shia and there is a feeling that Shia deserve to have had a word of apology from the regime for this crime."

However, as the dispute drags on and a national dialogue aimed at reconciliation remains stalled few have any hope that Bahrain's wounded society will heal any time soon.