Syrian refugees fear permanent exile in Lebanon's camps

- Published

Syrian refugee in Lebanon: "I would live anywhere but here"

Syrian refugees have flooded into Lebanon since the start of the conflict in their country three years ago, swelling the population by more than 25%.

Before the war, Syria was a lower middle-income country, and many of its refugees have been able to afford to rent vacant apartments throughout the country.

For the less fortunate however, shelter has been found in vast, informal tented camps in the Bekaa Valley - and in Beirut's Sabra and Shatila camps, known for the infamous massacre of hundreds of Palestinian refugees by Lebanese Christian militiamen during the 1982 Israeli invasion.

The camps are situated less than 4km (2.5 miles) from central Beirut's tree-lined promenades, uncomfortably entrenched in the predominantly Shia district of Dahiyeh.

Many Syrian Sunnis consider living in Sabra and Shatila a better option than other areas of Beirut

They are urban slums, confined to an area of about 1.3 sq km (0.5 square miles), with more than 10,000 people living in desperate conditions worlds away from the cosmopolitan districts barely 10 minutes' drive away.

"Life in Syria was better than it is here, and if I had the money to return I would," says Mohammed, an elderly man who brought his family from Yarmouk in southern Damascus.

"The rent cripples me - it's $200 (£120) for the room I share with my family. There are rats everywhere. The water is salty and stings your eyes when you wash. I haven't found a job in the camp yet, so I never know if I am able to provide the money for rent."

Repercussion worries

Refugees, both Palestinians and Syrians who are newly arrived at Sabra and Shatila, rely on aid money from local non-governmental organisations and from the United Nations.

Mohammed came to Lebanon from Damascus after his son was freed from a Syrian government prison. His son had been tortured and died from his injuries three months after the family moved into the Shatila camp in Beirut. “My Koran in its golden bag was the only thing of any value that I brought, because we left in such a hurry. It gives me strength, and provided guidance after my son died." (Images: Julia Macfarlane)

Rawan from Idlib says her most treasured possessions are photographs of her brother and father. “The last time I saw my brother, he left the house one night to go to get some petrol. He never returned and we never found out what happened to him. My father was heartbroken and he died three months later. These photographs are all that I have of them.”

Salaam is a Palestinian and used to live near Mount Qassioun in Damascus. “I didn’t feel like I was a refugee in Syria because I wasn’t living in a camp. We had a house and a normal life. Now I am living in Sabra and Shatila so I do feel like a refugee and more like a Palestinian. My [Palestinian] keffiyeh is the most important personal object to me, as my identity has become stronger since I moved into the camp.”

Nesrien came to Lebanon from Damascus with her brother who is being hunted by former comrades in the Syrian opposition. They are now both on the run. “When I realised we would have to leave Syria I started keeping all my bus tickets from Damascus. We want to claim asylum in a foreign country and when we have finally found a home I will put these tickets on the wall to remind me of the journeys I used to take.”

Wassam worked as a doctor in Yarmouk, a besieged Palestinian refugee camp in Damascus. He left Damascus with only his wallet and his oud, and after these photographs were taken he left Beirut to start a journey to Turkey with only those two items with him. He said that as a Syrian he did not feel safe in Lebanon.

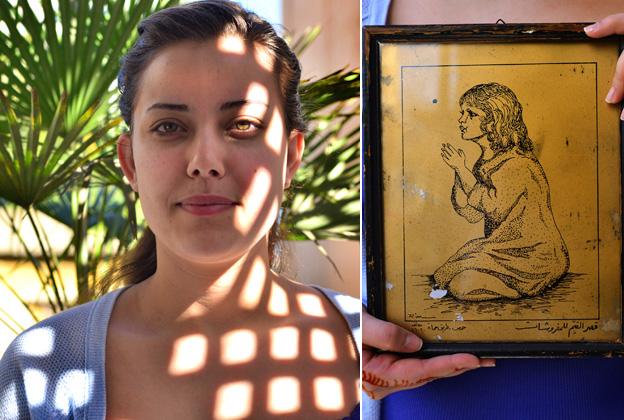

Reem left Homs after her mother sent her away because she had taken part in protests earlier in the Syrian uprising. “I take this painting with me everywhere I go. It’s older than I am, and it’s fragile and falling apart. It’s my father’s favourite painting, and the only thing I have from my old home. It reminds me to hold on to my hope, as the girl is praying with faith.”

Sabra and Shatila is officially a camp for the Palestinians who fled from the Arab-Israeli wars of 1948 and 1967, and humanitarian missions are run by the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), rather than the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

However, UNRWA has been informally providing some aid for Syrians on behalf of the UNHCR.

Some Syrians have been able to claim up to 75% of the cost of life-saving surgery, and some have been eligible to receive a "blue card", which entitles them to about $130 (£78) of food per month.

Eligibility is determined by family size, number of dependents, and whether or not potential recipients are in work.

However, there are many Syrians who have refused to register with UN agencies in Lebanon, out of fear that their names might be discovered by the Syrian government and that they might be accused of being defectors.

Those with relatives still trapped in Syria often worry that they will be subject to reprisal attacks, or that they themselves will be targeted if they ever return.

Najwa, a mother of five from the northern province of Idlib, came to the camp five months ago with her three daughters.

Her two sons remained in Syria. She recently learned that one of them had been killed.

The whereabouts of her second son are unknown, and because of this she does not want her full name to be published.

Environmental health conditions in Shatila are bad, with damp and overcrowded shelters

She lost her blue card two months ago and has been asking for a new one, but has been told that she cannot re-apply.

"Every two days the landlord comes to my house and says that if I do not pay the rent he will throw me out," she says.

"There is no-one here to help me - I receive money from a local Syrian NGO for food, but I do not have help with the rent. I have nowhere else to go - but anywhere would be better than here."

Armed gangs

Estimates for the population of Sabra and Shatila vary from about 10,000 to 22,000, swollen by the influx of refugees.

Despite the growth in the number of inhabitants, the camps are prohibited by the Lebanese authorities from expanding outwards, so both are slowly growing upwards.

Many breeze-block houses, which comprise small square rooms of about 25-30 sq m (80-100 sq ft), are now four or five storeys high, sometimes more.

The growing number of Syrian refugees has affected Lebanon's political, economic and social stability

The tapering streets, many of which are barely a metre wide, are now cast in near-permanent darkness, save for a few hours around noon when the sunlight can penetrate through the concrete canopy.

The lack of fresh air and abundance of open sewers, coupled with the incredibly dense population, also contributes to spread of disease in the camp.

With their rabbit-warren-like alleyways and informal housing, the geography of the camps make it nearly impossible for large NGOs to operate there.

Dozens of local militia and armed criminal gangs have taken advantage of the camp's inaccessibility to run black markets there. Their presence also prevents international organisations from obtaining insurance to allow their workers to enter.

'No return'

But it is this obscurity, as well as the comparatively low cost of living, which makes many Sunni refugees from Syria seek shelter there.

By the end of 2014, the Syrian refugee population in Lebanon could reach 1.5 million, according to the UN

Despite being located in predominately Shia southern Beirut, living among the mostly Sunni Palestinian refugees is considered a better option than other areas of the capital, where tensions with Christians have forced some Syrian families to leave.

Syrians adapting to life inside the camp spoke of their fears for the future.

When they first arrived in Beirut, some at the earlier stages of the Syrian uprising, they took with them the keys and deeds to their property, expecting to return in a matter of months.

As the conflict rages on though, many Syrians living with Palestinian refugees - whose community has now been in Lebanon for more than 60 years - fear they could share the same fate in years to come.