Iraq: Bloodshed and strife cast pall over polls

- Published

What you need to know about the election - in 60 seconds

At election time we tell political stories in numbers - from the turnout and the share of the vote, to the swings between party lists that will ultimately decide who wins and who loses.

And the Iraqi system certainly offers plenty of scope for the political mathematician - the outcome of the last election was so complex and finely-balanced that the business of forming a government took almost nine months.

"Nearly a world record," one former minister assured me. "Only the Belgians ever took longer and even then it was only once."

But the statistic that really matters in Iraq is not among the numbers they will be crunching as the weeks tick slowly past after polling day. Instead, it hangs over the country's political process like a shadow and feeds into every aspect of the debate here.

It is of course the death toll in acts of sectarian violence - suicide bombings and shootings - which would probably be headline news more often if it were not overshadowed by the even-grimmer statistics from neighbouring Syria.

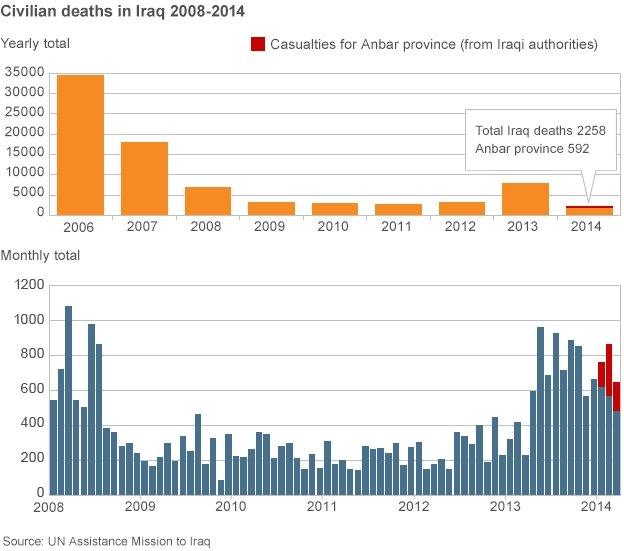

Last year for example 7,818 civilians died in the violence here - that is more than double the number of deaths over the whole course of Northern Ireland's long troubles.

And in February of this year alone, 1,000 were killed.

Some reports suggest that on top of that, as many as 1,000 members of the security forces loyal to Iraq's current Shia-led government have died fighting a Sunni insurgency in Anbar province in the first few months of this year.

Personal traumas

Violence in Iraq has returned to levels not seen for several years

These are staggering levels of attrition, which come for the most part not from battlefields but from city centres, where the targets for the suicide bombers are crowded market-places or bus stations.

As a simple exercise, we started asking everyone we met as we travelled around Baghdad how many people they knew personally who had died in political violence here. Even when you know the official statistics, the personal stories are really shocking.

One man whose memories go back to the Iran-Iraq war put the number at 200 or 300.

A journalist whose father, brother and sister had been killed also told us that her driver lost two friends last week. A television presenter admitted he was not sure who was alive and who was dead out of the contacts in his phone.

And a surgeon who treats the victims of trauma in one of Baghdad's Emergency Rooms told us that the events of the last 10 or 12 years had left the whole country in a state of psychotic shock.

It is a moot point whether it is possible to hold a viable election in such dangerous circumstances, but the truth is that holding it is better than the only alternative of not having one at all. That would be seen as a victory for those al-Qaeda-linked insurgents in Anbar who are democracy's implacable opponents.

Divisive figure

There is no real polling in Iraq so making predictions about the likely outcome of the election would be even more foolish than usual.

Prime Minister Nouri Maliki is bidding for a third term, but faces mounting opposition

But it is safe to assume the current Prime Minister Nouri Maliki, who is seeking a third term, will be a pivotal figure in the horse-trading and coalition building that will surely follow the vote.

It is not difficult to be a divisive political figure in Iraq, which has a large Shia majority but also substantial minorities of Kurds and Sunnis. There are Christians too but their numbers have been depleted by emigration.

Mr Maliki, though, is more divisive than most.

Some of his critics believe he is the tool of factions in Iran - where he lived for a period - while many others think he is more interested in promoting the interests of the Shia community from which he comes than in promoting national reconciliation.

He has also presided over a time of extraordinary corruption, which helps to explain why one of the world's largest oil producers has such visible problems of chronic poverty.

Mr Maliki has used his years in power to consolidate his grip over a variety of state institutions including the armed forces and the central bank.

He will be pulling every possible lever, making every possible deal with rival ethnic and religious groups, and twisting every arm among the minor parties on the Shia side to stay in office. The smart money won't be betting against him.

One of Mr Maliki's main rivals, Iyad Allawi, actually polled more votes than the prime minister in the last election but lost out in the tricky manoeuvrings which followed.

It will be interesting to see if he has learned from that experience.

Sunni-Shia schism

This all matters hugely beyond Iraq.

The Middle East is in the grip of an epic confrontation between followers of Shia Islam supported by the Shia power Iran and the Sunni world led by Saudi Arabia.

In smaller countries, the two regional powers fund political parties and fighting groups.

Nouri Maliki complains that the Saudi government pays for Sunni mercenaries to come to Iraq to fight his armed forces in Anbar province.

But Iraqi Shia militias send plenty of fighters to Syria - and the Lebanese fighters of Hezbollah may even have tilted the battlefield there in favour of the Assad regime with their Iranian-funded intervention.

This is a time when the transnational loyalties of Shia and Sunni Islam are starting to matter more in the Middle East than national identities within some of the nation states - like Iraq - that date back only to World War One.

These elections will give Iraqis a chance to choose a new government - and the rest of us a chance to see how the political mood here will adjust to those shifting sands across the Middle East.