Egypt: Why Sisi might struggle to deliver

- Published

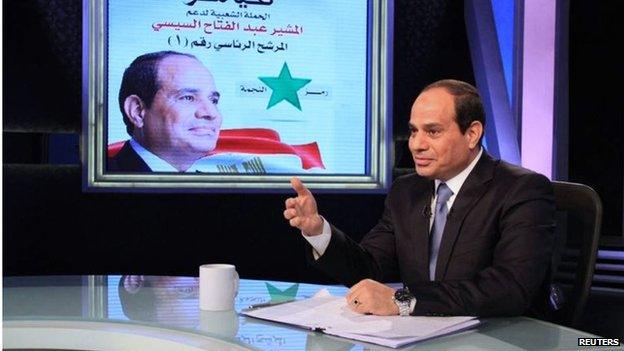

Sisi won by a landslide, but the powers of the president have been diminished

Although his victory was never in doubt, Egypt's new President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi made highly ambitious promises during his campaign. Now he is in power, turning them into reality will require more than just huge sums of money.

He has pledged to build 26 new tourist resorts, eight new airports and 22 industrial cities - in addition to solving chronic problems like high unemployment, fuel shortages and subsidies that are draining the budget.

He has also promised to cultivate 1.6m hectares (4m acres) of desert in a country suffering from a scarcity of water.

Mr Sisi himself estimated the cost to be over one trillion Egyptian pounds ($140bn; £84bn), in a country whose entire GNI in 2012 was $219bn, according to the World Bank, external.

The huge scale of the plans is only half the challenge - to carry them out, the new president will have to contend with a bureaucracy and administrative system often described as incompetent, cripplingly sluggish and mired in corruption.

According to anti-corruption campaigners Transparency International, Egypt ranks 114, external on the index of most corrupt countries in the world ("1" being the least corrupt).

Many economists believe that corruption is the main reason behind the notorious inefficiency, lack of development and poverty in Egypt.

However, restructuring government and public bodies would require drastic changes in policies, people and laws - changes which would be fiercely resisted by those who benefit from the status quo.

Mr Sisi will also need highly efficient, well-trained and incorruptible teams - and the last three years in Egypt have proved that such individuals are far from readily available.

Constrained powers

If he intends to keep his promises, Mr Sisi will need to shake up the administrative system and have a distinguished cabinet to rely on. But is that possible?

The powers of the new president will be much more limited than those of previous Egyptian leaders. The new constitution, external, adopted in January 2014, contains unprecedented tough checks and balances on the president, which could constrain his ability to achieve these promises.

The president will want to pick a cabinet which he thinks can best deliver on his campaign pledges, but his nominations need to be passed by parliament.

Sisi promised a huge building programme, including new cities and airports

Moreover, according to the constitution, "The president shall appoint a prime minister who is nominated by the party or the coalition that holds the majority or the highest number of seats in the House of Representatives."

Put simply, this means that the president could be forced to work with a PM and cabinet who have different views on how to deal with the multi-faceted crises in Egypt.

If they do not deliver, Mr Sisi will not be able to dismiss them.

In a break with the past, the new president has no constitutional rights to sack the cabinet or even a single minister without the approval of the parliament.

Dealing with civil servants will prove much more difficult for Mr Sisi than dealing with the military staff, especially since the Egyptian Labour Law makes it very difficult to get rid of employees.

The president would need the backing of parliament to amend such laws - but will the members of parliament agree, and if they do, on what conditions?

MPs are usually aligned to ministers as the latter can get things done for them and their constituencies.

Hence, these MPs are more likely to support ministers in confrontations with the president. MPs can take reassurance from the fact that the president has no power to dismiss the cabinet or to legislate without the consent of parliament - whereas parliament has the power to make laws without the approval of the president.

Furthermore parliament has the power to depose and try the president and to withdraw confidence in him after a public referendum - whereas the president has no power to dissolve parliament without a referendum. This leaves the president weaker than parliament.

Lobby groups

In spite of the banning of the Muslim Brotherhood, Islamist opposition still exists on the ground.

They have the means and experience to put forward candidates in forthcoming parliamentary elections. Once in the parliament, they are expected to vehemently oppose Mr Sisi and spare no effort to avenge the deposing of "their" President Mohammed Morsi.

Beneficiaries of the Mubarak era are also expected to form lobby groups in parliament to protect their interests and challenge any laws or changes that might pose a threat to them.

As a result, Mr Sisi's declared intention to give a greater role to the state in the economy and to force down prices and profits could lead to confrontations in parliament.

Sisi's options

The new president still has various options at his disposal.

He could just to ignore parliament and rule as an authoritarian - but this would only create more problems for the country and himself.

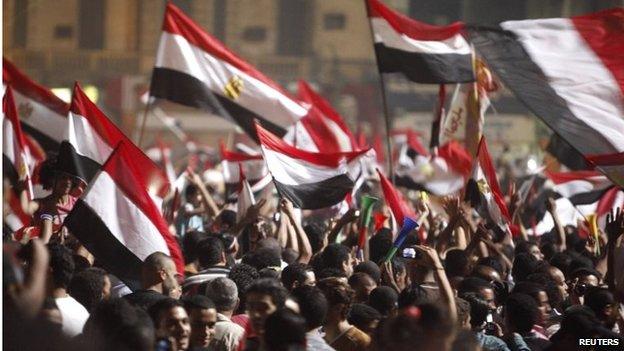

Patience among Egyptians is running short after three years of turmoil

Alternatively he could work hand-in-hand with MPs, although this is highly unlikely as cartels who feel their interests threatened are expected to have parliamentary lobbies.

The president might resort to amending the constitution to acquire more powers, but this would also depend on parliament acquiescing.

Mr Sisi might decide the safest way would be to make a constitutional declaration to amend articles that restrict his authority, while he has the constitutional power to do so before a new parliament is formed.

Furthermore, Mr Sisi has announced that he will not wait for the formation of the parliament to issue laws.

However, a new constitutional declaration would be reminiscent of the 2013 declaration of Mr Morsi, which caused turmoil in the country.

It would also intensify criticism from Islamists and other opposition groups, and fuel concerns in the West about the direction Egypt was heading.

How the average Egyptian would react is harder to predict. Egyptians have surprised the world more than once in the last three years and they could well do so again.