Battle for Mosul: Critical test ahead for Iraq

- Published

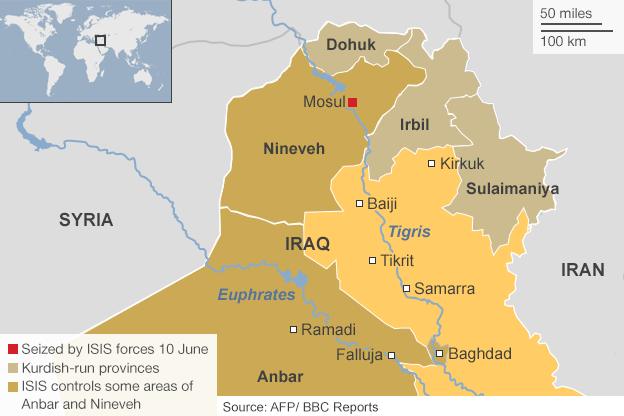

Since 6 June the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Shams (ISIS) has seized control of the western half of Mosul, Iraq's second largest city and a major political and economic centre in the northern Nineveh province.

As hundreds of ISIS fighters fought their way from the desert suburbs into the city centre, Iraqi security forces suffered a dramatic collapse of morale despite outnumbering ISIS fighters by more than 15-to-one.

By 9 June, ISIS had overrun the provincial council and governor's offices, high security prisons, the Federal Police headquarters, television stations and the international airport.

Now the Iraqi federal government must gather its forces for a counter-offensive. Unlike Fallujah, which was lost to ISIS in January 2014, Mosul is too important to be cordoned off and besieged.

Simple assault

In addition to being Iraq's second largest city, Mosul is informally the political and economic capital of Sunni Iraq.

The city of 1.8 million has a Sunni Arab majority that includes more than 7,000 former Saddam-era officers and more than 100,000 other former soldiers, many of whom were removed from service by de-Baathification - the purge of Saddam Hussein's supporters when he was deposed in 2003.

Notable Mosul residents include parliamentary speaker Osama Nujaifi and his brother, Nineveh governor Atheel Nujaifi, who are two of the most senior Sunni politicians in Iraq.

It is not yet clear whether it is only ISIS forces involved in the Mosul takeover

Close to militant safe havens in Syria and Iraq's western desert, Mosul has also long played a key role in the logistical and fundraising efforts of al-Qaeda in Iraq and its successor ISIS.

This factor made it relatively simple for ISIS to prepare the assault and to surge forces to the western suburbs of Mosul on 6 June.

A day earlier a similar attack was launched by 200 ISIS fighters on the shrine city of Samarra 250km to the south, though ISIS were held off in the south-east of the city by Iraqi reinforcements and attack helicopters.

In Mosul, the militant group experienced far greater success, winning all-important psychological dominance over the security forces in three days of progressively heavy fighting in western Mosul.

An effort will undoubtedly be made to recover the city's key military and political locations as Iraq's security forces recover their balance. ISIS will seek to reinforce and fortify its new territory.

Rallying point?

Governor Atheel Nujaifi made a desperate appeal on the night of 9 June for citizens to use their personal weapons to form self-defence militias in their neighbourhoods in an effort to limit ISIS gains.

The next step will be the regrouping of the disintegrated units, including those where policemen and soldiers stripped off their uniforms and abandoned vehicles, weapons and outposts.

New armoured, artillery and aerial forces will be brought up to Mosul for the operation, though scraping together such forces is getting increasingly difficult due to the growing number of major ISIS assaults in the Baghdad suburbs and cities like Ramadi, Samarra, Tuz Khurmatu, Sharqat and Mosul.

The only source of fresh forces available in Iraq is the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) Peshmerga, an infantry force with some artillery and light armoured vehicles.

Security forces have been placed on a state of "maximum alert"

Peshmerga forces have recently moved forwards along the line of disputed territories claimed by both the federal government and the KRG, including securing the areas of Mosul city east of the Tigris River.

Gaining the KRG's active support to take part in the clearance of western Mosul may only be possible if Baghdad is willing to make concessions to the Kurds on issues such as the international marketing of KRG oil and revenue-sharing between Baghdad and Iraqi Kurdistan.

The importance of Mosul could mean that it becomes a rallying point for Iraqi political factions.

For the Baghdad government of caretaker Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, the recovery of Mosul is a test of leadership at a critical moment when he is seeking reappointment.

Iraq's Kurds need stability in Mosul, which is just one hour's drive from the KRG capital of Irbil.

Many Kurds live in or around eastern Mosul and ISIS control of the city could pose a grave security threat to the Iraqi Kurdish region, which prides itself on providing a safe environment for investors.

Shock waves

Iraq's Sunni political, tribal and religious leaders have the most to lose from ISIS's growth as they are the first to be targeted when the militant movement takes over an area and forms its own new institutions.

Taking an optimistic view, these overlapping interests could create the potential for political dialogue and speedier government formation, potentially lessening tensions between Baghdad and the KRG.

Alternatively, ongoing discord between the Maliki government and its Kurdish and Arab opponents could disrupt the government's counter-offensive, allowing ISIS to consolidate its hold on western Mosul.

Some 150,000 people are believed to have fled the city in the wake of the takeover

If ISIS were to develop firm control of the city they would have replicated their success in seizing an administrative and economic capital in Syria's Raqqa province.

In fact, a consolidated ISIS caliphate in western Mosul - with a population of over a million people - would be a far greater success than anything the movement has achieved in Syria and would send shock waves throughout the region.

For this reason we can expect hard fighting to follow as the Iraqi government uses every resource at its disposal - military forces, new local militias, air power, Iranian-backed Shia volunteers from southern militias, the Kurdish Peshmerga plus US intelligence and logistical support.

The battle for Mosul is shaping up to be a critical test of the political and military vitality of the Iraqi state.

Probably only a political-military solution supported by all of Iraq's factions can restore the situation but it is too soon to gauge whether the Iraqi government recognises this reality.

Dr Michael Knights is the Lafer Fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. He has worked in all of Iraq's provinces, including periods spent embedded with the Iraqi security forces.