Could Iraq conflict boost Kurdish dreams of independence?

- Published

Kurdish fighters are seen as a bulwark against Sunni Muslim insurgents

As Iraq descends deeper into chaos and the fires burn closer to Baghdad, the Kurds in the north have quietly taken advantage of the tumult to expand and tighten their control in the oil-rich Kirkuk province, long the object of their dreams and aspirations.

The move was both defensive and ambitious, carrying strong elements of both opportunity and risk.

"Part of the motivation was to avert a humanitarian disaster," said a senior source in Irbil.

"Had we not filled the vacuum left by the Iraqi army's departure, everybody would have flooded into the Kurdistan region. We had half a million people banging on our doors.

"It's a lot simpler to send 100 peshmergas (Kurdish military forces) to hold the fort and keep security, so that people could stay put. Once our units went in, the displaced started going back."

But there's clearly more to it than that. The Kurdish media have been hailing the step as a historic reunification of Kurdish lands.

Jewel in their crown

Kirkuk city, which has a mixed population of Kurds, Arabs and Turkmen, has long been a thorny issue in Iraqi politics.

Iraq's Kurds have long-hoped to control the oil-rich city of Kirkuk

Its special status as a disputed city was recognised in the post-Saddam Hussein Iraqi constitution, which called for the situation in the city to be "normalised" by:

The return to the south of Arabs settled there by the deposed ruler

The restoration of expelled Kurds

A census

A referendum on whether the province should join the Kurdistan autonomous region.

But that has never happened, and Kirkuk, as well as other disputed areas along the Arab-Kurdish ethnic fault line, have been flashpoints for friction between Kurdish forces and Iraqi government troops.

Now, the latter have melted away, leaving Kirkuk to fall into the hands of the Kurds like a ripe fruit.

With the rest of Iraq apparently disintegrating along sectarian lines, and the central government in Baghdad in disarray, it will clearly be a long time before an Iraqi authority can challenge the Kurds' absorption of what they have long seen as the rightful jewel in their crown.

The Kurdistan region has already angered Baghdad by going its own way and selling its oil and gas directly to and through its northern neighbour Turkey, with which the regional government (KRG) has developed a close partnership despite historic Turkish suspicions of Kurdish nationalism.

Now it seems likely that the acquisition of Kirkuk, both the city and the province with its rich oilfields, will boost the trend towards outright independence for the Kurdistan region.

Dominant forces

"Absolutely, it brings independence a step closer," said a well-placed source.

"We have lost hope in the sanity of the people governing Iraq. We don't want to be part of the failure of something for which we're not responsible. Nobody gave more than us in the effort to keep Iraq together, but now we're giving up, there's no hope."

But the move is not without risks.

It brings Kurdish forces into direct proximity with the militants who have taken over in Mosul and other adjacent areas.

In recent years, Kirkuk has already seen many suicide and other bomb attacks attributed to Sunni radicals, which are very rare inside the KRG autonomous area itself.

Iraqi Kurdish forces say they took control of Kirkuk as the army fled

If instability spreads, it could affect the current boom in investment and economic activity in Kurdistan, which has flourished while the rest of Iraq has largely stagnated and been mired in turmoil.

If the Sunni areas are starting to go their own way, much will depend on the composition of the dominant forces taking part in that process.

Other strands

So far, the public face that has resonated around the world has been that of the ultra-radical al-Qaeda offshoot known as ISIS, the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant.

But as with the anti-US insurgency from 2004 on, there are clearly other strands to the revolt, which explains the resonance it is having, and the speed of its movement through the mainly Sunni areas on which it is concentrating.

The Kurds have no sympathy for the ISIS radicals, but they are in touch with other elements, including tribal leaders and commanders of the Military Councils of Iraqi Revolutionaries (MCIR), which includes many experienced former Iraqi army officers.

The Kurds have been given assurances from the latter that they will not encroach on the borders of the KRG autonomous region, according to an MCIR spokesman.

Tribal leaders and former army officers are believed to be fighting alongside ISIS militants in the Sunni revolt

The MCIR claims that overall, its fighters are the most significant element in the revolt, with tribal militants in second place, and ISIS only third despite the media attention they command.

When Sunni rebels took over the city of Fallujah, west of Baghdad, in January, Prime Minister Nouri Maliki asked the Kurds to send peshmerga forces to help drive them out, sources say.

But the request was turned down. The Kurdish leadership's message to the MCIR conversely was that Irbil would not be against the Sunnis taking the road of establishing their own autonomous area, following the lead of Kurdistan itself.

That would clearly not apply if ISIS emerged as the dominant force in self-administering Sunni areas. Its philosophy and practices are so extreme that it has even been disavowed by its parent leadership, the international al-Qaeda movement headed by Osama Bin Laden's successor Ayman al-Zawahiri.

A future scenario where the Kurdish forces helped "moderate" elements such as the MCIR to oust ISIS is not hard to envisage.

Already there are signs of a potential conflict between strands of the rebel movement, although they are cooperating for the time being.

"There is no friction or clashes between us at the moment, but we plan to avoid them until we are settled and operations are finished, then we will kick them out of Mosul," said an MCIR source.

"We are warning their leaders that if they perpetrate any violations, they will become our first enemy, so they are behaving so far."

Stir hostility

Politically, the clerical body which is the spiritual point of reference for mainstream militant Sunni groups, the Association of Muslim Clerics (AMC), has put out a statement which clearly takes issue with the radical declaration put out by the ISIS spokesman, Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, the day before.

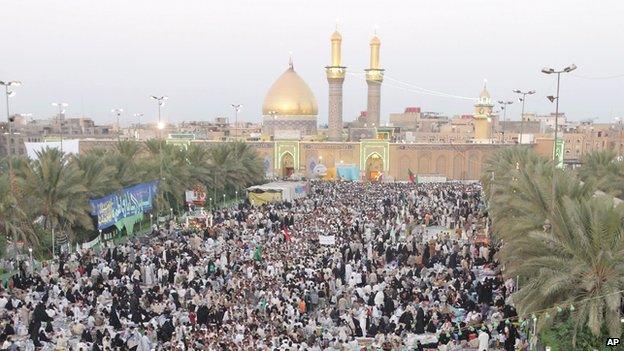

He called for revenge and score-settling in Baghdad, and for the militants to march on the holy Shia city of Karbala to the south of the capital.

That would clearly be a recipe for sectarian carnage and civil war between Sunnis and Shias, something the AMC said is absolutely not on the agenda.

Karbala is among the holiest cities for Shia Muslims

"Calls for the revolutionaries to head for Karbala, Najaf and elsewhere are rejected, unacceptable and irresponsible on the part of those issuing them," the AMC statement said.

"It would stir hostility to the revolution and make it fail, diverting its goal from helping the oppressed to stirring up sectarian conflict between the sons of our one people, quite apart from the fact that everybody knows that most of the Iraqi people in the south reject Maliki and his gang, and suffer his oppression like the rest of us."

The AMC insisted that forgiveness and tolerance should be the keynote in administering the "liberated" areas, and that nothing should be done to prejudice people's livelihoods or impose dress codes on them, even if they were not in line with strict Islamic precepts.

In another clear reference to ISIS, it said that no group should claim to represent the entire revolt and take strategic decisions without consultation.

It also called for the immediate release of the 49 Turkish nationals seized by ISIS from the consulate in Mosul, saying this risked alienating a powerful neighbour and provoking intervention.

But even the AMC embraced the goal of reaching Baghdad, "because the ruling regime is there, the source of oppression and crimes against the people, so there is no other way of lifting the yoke as long as the regime fails to look after others."

Room for compromise

So the seeds of an incipient struggle within the rebel movement are clearly there, though the AMC stressed the need to avoid the kind of chaos and in-fighting afflicting opposition groups in the anti-government uprising in Syria.

Clearly, the current Sunni revolt has much more to it than the intrusion of foreign jihadist "terrorists", as Prime Minister Maliki has claimed.

The Americans and others are aware that the turmoil reflects Mr Maliki's failure to draw major Sunni political forces into the political process and give them a stake, one of several factors inhibiting them from producing a forceful and determined response to his appeals for help.

Despite their visible differences, the various elements in the Sunni revolt are agreed on the need to push towards Baghdad, a campaign that is likely to see movement from the western side - Anbar province - as well as from the north.

But as with the Kurds in the north, the course of events will depend a great deal on which strand predominates within the rebel movement.

If ISIS prevails, open-ended sectarian strife can be expected. But if the more moderate groups assert themselves, there may be room for compromise and accommodation.