Iraq's central government suffers mortal blow

- Published

Demonstrators shout slogans in support of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant in Mosul

Regardless of whether the Iraqi government in Baghdad rolls back the recent military advances by the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), the central authority has suffered a mortal blow.

ISIS's takeover of most of the so-called Sunni Triangle, as well as Mosul, the second largest city with almost two million people, hammers a deadly nail in the coffin of the post-Saddam Hussein nation-building project.

Fragile Iraqi institutions now lie in tatters.

It is doubtful if Baghdad could ever establish a monopoly on the use of force in the country, or exercise authority and centralised control over rebellious Sunni Arabs and semi-independent Kurdistan.

The best-case scenario for Iraq is devolution of power from the centre in Baghdad to local Shia, Sunni Arabs and Sunni Kurdish communities; the worst is splintering of the country to three separate entities.

ISIS's swift advance has exposed the state's structural and institutional weaknesses, as well as a deep ideological and sectarian rift in society.

After eight years in office and monopolising power, Prime Minister Nouri Maliki has delivered neither security nor reconciliation and prosperity.

Iraqi security forces, which number hundreds of thousands of men, almost disintegrated under a stunning sweep of only a few thousand, lightly armed al-Qaeda-linked fighters.

More than a decade after the Americans removed Saddam Hussein from power and dissolved his army, the reconstituted military lacks a unifying identity and professionalism, and is riddled with corruption.

For example, in Mosul, ISIS militants had a joy-ride through the city because senior and junior officers had already deserted their positions and weapons, and ordered soldiers to flee home.

A security force in Mosul made up of tens of thousands melted away.

Shia volunteers have rallied to defend the state and holy sites

Coming to the rescue of a sinking ship, a representative of the highest Shia authority in the land, Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, said the "defence of Iraq and its people and holy sites is a duty on every citizen who can carry arms and fight terrorists".

A parallel army of an estimated 100,000 volunteers, mainly Shia, has joined the fray, increasing the risks of sectarian strife.

Concerned about misinterpretation of his call to arms, Ayatollah Sistani's office subsequently qualified his statement by warning his supporters against "any behaviour that has a sectarian or a nationalist character that may harm the cohesion of the Iraqi people".

Broken system

It is misleading to exaggerate ISIS military prowess and exploits as many reports in the Western media do.

Its strength stems not only from the weakness of the Iraqi state, but also from the communal and social cleavages that are tearing society apart; it is a manifestation of a bigger revolt by (tribal) Sunni Arabs against what they view as Mr Maliki's sectarian authoritarianism.

Soldiers and police retreated en masse as the militants swept into Mosul last week

At the very heart of the fierce struggle raging in Iraq is a broken political system, one based on "muhasasa", or distribution of the spoils of power along communal, ethnic and tribal lines, and put in place after the US invaded and occupied the country in 2003.

Sunnis Arabs, particularly in the last four years, have felt excluded and disfranchised by what they view as Mr Maliki's sectarian-based policies.

When the US left Iraq in 2011, the al-Qaeda brand was in decline, unpopular among Sunnis.

Three years later, ISIS has revived by finding a "hadana shaabiya", or social base, among dissatisfied and alienated Sunni Arabs.

Devolution

Seizing the opportunity afforded by the Syrian armed uprising against President Bashar al-Assad, ISIS chief Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi expanded his activities to the neighbouring country and established a powerful base which has yielded new recruits and precious financial and operational assets.

ISIS has aligned itself with insurgent Sunni groups, such as officers of Saddam's dissolved army, and co-opted hundreds of these skilled fighters to its ranks, a turning point in its ability to plan and execute complex operations in both Iraq and Syria.

In Falluja, Mosul, Tikrit and other towns, Sunnis welcomed al-Qaeda militants as liberators and armed men joined the advancing units.

The offensive has displaced hundreds of thousands of people in Nineveh province

More alarming, Sunni officers who deserted their bases are reported to have said that they would not fight for Mr Maliki's government, a development that shows the gravity of the sectarian-political rift in Iraq today.

This helps explain the shattering collapse of Iraqi security forces.

Sunni tribes and disgruntled former army officers sealed the fate of the Sunni Triangle.

ISIS is only a powerful vehicle for Sunni Arab grievances, though a vehicle that could ultimately crush both Sunnis' aspirations and the Iraqi state. The writing is already on the wall.

In Mosul, ISIS has already laid out its iron law which caused disquiet and alarm among its religious-nationalist and tribal allies who advised caution and prior consultation.

Even if the Iraqi state recaptures the cities seized by ISIS, it would be unable to pacify the population without decentralisation of the decision-making and devolution of power to the local level.

Old order dead

Various communities should be empowered to govern themselves and feel invested in the national project, a vital task to rescue the fragile Iraqi state and rid the country of ISIS and other insurgent groups.

The old order is dead. There is an urgent need to reconstruct the broken political and social system along new lines of citizenship and the rule of law.

The ISIS assault has allowed Kurdish Peshmerga forces to seize control of Kirkuk and its oil reserves

Neither reconciliation nor institution-building would occur without a new social contract based on the decentralisation of power and an equitable sharing of resources.

There is no assurance of success given the widening fault-lines among Iraqis and the lack of trust.

Emerging as the biggest winner, the Kurds might be reluctant to surrender the gains recently made with their occupation of the strategically important, oil-producing city of Kirkuk and the consolidation of their Kurdistan borders.

In a similar vein, the Sunni Arab leadership has not come to terms with the new realities of post-Saddam Iraq and still entertains illusions about ruling the country.

Tribal chieftains have acted as cheerleaders for ISIS and seem intoxicated by a Pyrrhic victory.

Shia monopoly

Mr Maliki, along with the Shia leadership, bears a greater responsibility for Iraq's failure.

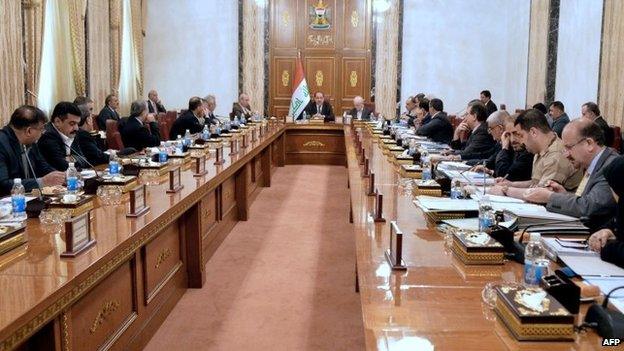

Western countries have urged Mr Maliki to reach out to Sunnis to rebuild national unity

Having taken ownership of the country after the US occupation and overthrow of Saddam Hussein, the Shia leadership has treated Sunni Arabs like second-class citizens and has equated its numerical majority with a licence to monopolise power.

Iraq's future depends on the willingness of the dominant social classes to rise up to the historical challenge and prioritise the national interest over the parochial.

If history is a guide, the ruling elite might once again fail the Iraq people with catastrophic repercussions for the war-torn country and the regional and international system.

Fawaz A Gerges holds the Emirates Chair in Contemporary Middle Eastern Studies at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is author of several books, including The New Middle East: Social Protest And Revolution In The Arab World.