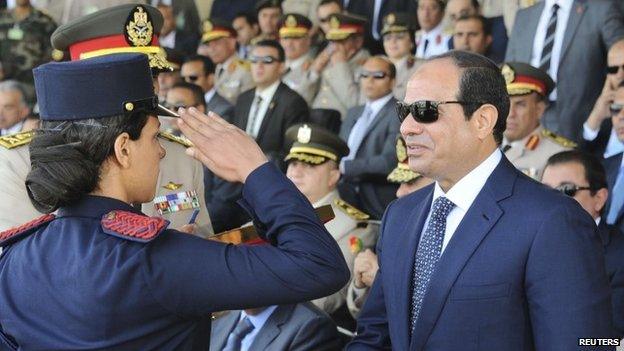

Egyptians uncertain about future under President Sisi

- Published

President Sisi has warned Egyptians that democracy will not be possible for 25 years

A year ago, many hailed him as their saviour for overthrowing President Mohammed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood.

They elected him president in May, with a 97% majority of votes cast.

Now Egyptians are trying to find out how retired field marshal-turned-President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi plans to tackle Egypt's problems.

Puzzling personality

For a man who has effectively been in power for a year, President Sisi has revealed little about himself and above all about his vision for Egypt.

He was not elected on the basis of his programme. One aide says he did not present one until the very end of the campaign in order to avoid unnecessary debate and controversy.

Nor was he elected on the basis of his charisma. A military man all his life, he comes across as serious and dignified, but not inspiring.

He is not an eloquent public speaker, although people who meet him find him sincere and convincing.

He was elected above all for having overthrown President Morsi.

A year later, most Egyptians are still happy about the demise of Mr Morsi, but somewhat puzzled about Mr Sisi.

Egypt's military have followed President Sisi's lead by pledging $140m to help the economy

During a recent trip, the questions I asked Egyptian politicians, analysts, and businessmen about President Sisi's policies elicited remarkably numerous answers along the lines of "I really do not know", including from people who repeatedly participated in meetings with him.

The first few weeks of Mr Sisi's presidency have begun to provide glimpses into his personality, or at least the public persona he has chosen.

They have also given some indication about his political views, but have revealed almost nothing about how he intends to tackle urgent economic problems.

Leading by example

Mr Sisi wants to be seen as a serious, honest, hard-working, and pious president.

During the election campaign, he repeatedly warned Egyptians of the hard work ahead, and he is continuing to do so now.

President Sisi tells Egyptians to cycle and walk more to save the country money

He has told his ministers they must set an example by being in the office by 07:00.

He emphasises the contribution individuals can make towards solving Egypt's problems. If people rode their bicycles or walked to work, he says, they would save the country millions in oil imports.

He has announced that he is donating half his salary and half his personal assets to support the Egyptian economy - a move that will force senior officials and prominent businessmen to do the same. In fact, the defence minister has already announced the military will donate $140m (£82m).

He has ordered the ministry of finance to enforce rules on maximum wages.

He talks about the importance of religion and leaves no room for doubt about his own commitment to Islam: his forehead bears the mark that develops when a person prays regularly.

He has stressed that Egypt is committed to "correcting the religious discourse" and freeing it from extremism.

New initiatives and laws (many announced by the outgoing interim President Adly Mansour after the election but before the inauguration of Mr Sisi) convey the same messages about rectitude and morality.

Egypt's ministry of youth and sports has declared it will combat atheism among young people.

President Sisi used a hospital visit to publicise his commitment to tackling Egypt's cases of sexual assault

The ministry of interior has banned religious slogans on vehicles. The interior minister also says he'll form a new department that will handle sexual assault cases, and Mr Sisi has already demonstrated his personal interest in the issue, by being photographed on a hospital visit to a woman receiving treatment after an assault in Cairo's Tahrir Square during his inauguration celebrations.

Top-down political control

On the political front, however, the message from the president and his government is one of strict top-down control over all aspects of life. During the election campaign, Mr Sisi said democracy in Egypt would be impossible for at least 25 years.

His actions, too, leave no doubt that he prefers order and discipline over individual choice. The laws governing the forthcoming parliamentary elections guarantee a weak parliament because they favour individual candidates over political parties.

Mr Sisi has established a Supreme Council for Legislative Reform by decree, which will be able to draft new laws and leave the parliament to do the rubber-stamping.

He has also tightened control over religion and education. Only preachers licensed by al-Azhar, one of the main centres of Sunni Muslim learning, will be allowed to deliver sermons, and Mr Sisi will personally appoint university presidents and deans.

Repression of the Muslim Brotherhood continues, with over a thousand members sentenced to death by the courts in summary trials. Young people who defy the anti-protest law brought in last December have been given tough sentences.

So have al-Jazeera journalists accused of fabricating stories. Even street vendors and people who litter have been targeted, in an effort to clean up the cities.

Uncertainty over economy

On the most important challenge he faces - reviving the economy - President Sisi has sent out very few and contradictory signals, and, with about 25% of ordinary Egyptians living below the poverty line and a similar percentage hovering just above it, he must act soon.

After his election win, President Sisi tells Egyptians it is now "time to work" to rebuild the economy

The business community is waiting for clear signals about his intentions.

Even Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait, all countries which have poured billions into the Egyptian economy since President Morsi's overthrow, are hinting they will not continue their support indefinitely, particularly if Egypt does not adopt clear policies and major reforms.

Mr Sisi has done neither. His approach is confusing: he states the private sector has a role to play, if not a duty to invest. But he remains committed to the state sector and has put the military in charge of managing the massive housing projects financed by the United Arab Emirates.

Above all, the government cannot reach a decision on the urgently needed reform of food and energy subsidies, which occupy a third of the budget.

Plans are periodically announced but never implemented, in case they lead to unrest.

Egypt's economic growth forecast is far too low to alleviate poverty for its rapidly growing population

The latest announcement, on 30 June, that the government will slash energy subsidies by the equivalent of $5.6bn (£3.3 bn) was typically vague: savings will be achieved through "redistribution and restructuring," he has said, but without a timetable.

Egyptians still have a lot to discover about their new president.

Marina Ottaway is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and a long-time analyst of political transformations in Africa, the Balkans, and the Middle East.