Syrian conflict: Untold misery of child brides

- Published

Girl married at 14 and abandoned by husband: 'The wedding was the saddest day of my life'

There is an alarming rise in the number of Syrian refugee girls in Jordan being forced into early marriages, according to the new figures from the United Nations.

As Orla Guerin reports from Zaatari refugee camp, poverty is forcing some families to effectively sell their daughters to much older men, and there is now an organised trade in young girls.

In a prefabricated cabin in the sprawling camp, a girl, 13, sat on the floor engulfed by a frilly white dress, and a hooded silk cape.

She was surrounded by children, not much younger than her, clapping and singing a nursery rhyme.

What looked like a game of dressing-up was in fact her wedding reception. Her Mother looked on from a distance and wept - for her war torn homeland, and perhaps for her daughter. She asked us not to give their names.

No choice

Earlier, at a makeshift beauty salon, a fellow Syrian refugee curled the girl's hair and layered make-up on her face - the finishing touches to the end of a childhood.

Alaa, a 14-year-old resident of the Zaatari camp, married her cousin and is now pregnant and worried

The bride told me her 25-year-old husband had been chosen by her family and she had never seen him before. She appeared relaxed, and said she was happy to be getting married. The reality is she had no choice.

Almost one third ( 32% ) of refugee marriages in Jordan involve a girl under 18, according to the latest figures from Unicef. This refers to registered marriages, so the actual figure may be much higher. The rate of child marriage in Syria before the war was 13%.

Some families marry off their daughters because of tradition. Others see a husband as protection for their daughters, but the UN says most are driven by poverty.

City of the dispossessed

"The longer the crisis in Syria lasts, the more we will see refugee families using this as a coping mechanism," said Michele Servadei, deputy Jordan representative for Unicef. "The vast majority of these cases are child abuse, even if the parents are giving their permission."

Classes are held outside the clinic in the camp to spare young girls from adult burdens

In Zaatari camp - a city of the dispossessed sprouting in the desert - some are married before they reach their teens.

Jordanian midwife Mounira Shaban, known in the camp as "Mama Mounira", was invited to the wedding of a 12-year old girl and a 14-year old boy. She could not bring herself to attend.

"I felt like I wanted to cry," she said. "I felt like she was my daughter. I think this is violence. It's a shame. If a girl is 18 or over they think she is old and will not marry."

Girl married at 15, who is getting a divorce: 'I was just dreaming of the wedding dress'

Mounira tries to spare young girls from adult burdens. At her clinic she lectures refugees, sitting on benches in the sand, about the problems faced by young brides.

"They don't know how to cook," she said, "and they don't know how to read and write. They have to take care of their husbands, when they want to go outside and play. Many of them get divorced."

That is what is ahead for a slender 17-year-old we met who did not want to be identified. She was married at 15 and has a treasured baby girl.

'Not scared of divorce'

The two-month old wriggled in her arms, snug in a pink and white baby-grow, and her mother's love. But her husband is threatening to take the child away, as the price of her freedom.

Zaatari is a camp is an expanse of the dispossessed, a place of interrupted lives

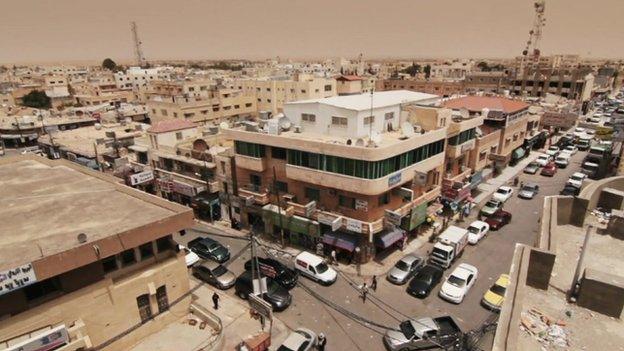

Not far from the camp in the city of Mafraq there is an organised trade in young girls, according to Syrian refugees and local aid workers

"I am not scared of divorce. I know I will start a new life, but I am scared that my daughter will be taken from me," she said. "I will die without her. A mother's heart burns if her child is taken from her."

At the other side of the camp we met Alaa, a shy young girl in a floral headscarf. Back home in Syria she loved school but now her only lessons are in housework.

When we heard the sound of dishes being dropped her 20-year old husband Qassem joked that she was no good at cooking. Not surprising perhaps. Alaa - an orphan - is just 14.

She fled Syria with her extended family. When she had to share accommodation with male relatives she was married off to Qassem, her cousin. The couple seemed happy in each other's company, but Alaa is pregnant, and worried.

"I am scared of having the baby because I feel I won't be able to look after it," she told us, over a pot of sweet tea. "I wish I could have continued my studies and become a doctor and not got married so young."

Shopping for brides

Not far from the camp, in the city of Mafraq, there is an organised trade in young girls, according to Syrian refugees and local aid workers.

Some young brides are abandoned as soon as they become pregnant

Babies born in the camp face an uncertain future being brought up by mothers who in many cases are themselves still children

It involves Syrian brokers and men - mainly from the Gulf States - who present themselves as donors, but are actually shopping for brides.

They prey on refugee families, living in rented accommodation, who are struggling to get by.

Local sources say the going rate for a bride is between 2,000 and 10,000 Jordanian dinars ($2,800/£1,635 to $14,000/£8,180) with another 1,000 ($1,400/£818) going to the broker.

"These guys from the Gulf know there are families in need here," said Amal, a refugee, and mother of four. "They offer money to the family and the first thing they ask is 'do you have girls?' They like the young ones, around 14 and 15."

Some men want even younger children like 13-year-old Ghazal, a slight but spirited girl with blue nail varnish.

A 30-year-old Saudi man proposed to her, but she turned him down - against her family's wishes. She told us she was determined to continue her studies, but it is unclear how long she can defy her parents.

Saying "no" was not an option for another teenage refugee in the city, who had dreams of becoming a lawyer. Instead she was married off at 14 to a 50-year-old from Kuwaiti. She told her story from beneath a black veil, which concealed her face, but not the pain in her eyes.

"Usually a girl's wedding day is the happiest day in her life," she said, "for me it was the saddest. Everyone was telling me to smile or laugh but my feeling was fear, from the moment we got engaged."

Her mother - a Syrian war widow - sat alongside. She told us she accepted 10,000 Jordanian dinars ($14,117/£8,248) for her daughter because she had seven more children she could not provide for.

"I would never have considered this back in Syria but we came here with nothing, not even a mattress to sleep on. I thought the money would secure the future of my children. He took advantage of our situation."

Instead of a better future, the family now has another mouth to feed. Her daughter has a four-month-old baby boy. His Kuwaiti father has never met him. He abandoned his young bride as soon as she became pregnant.