Israelis along the Gaza Border keep calm and carry on

- Published

.jpg)

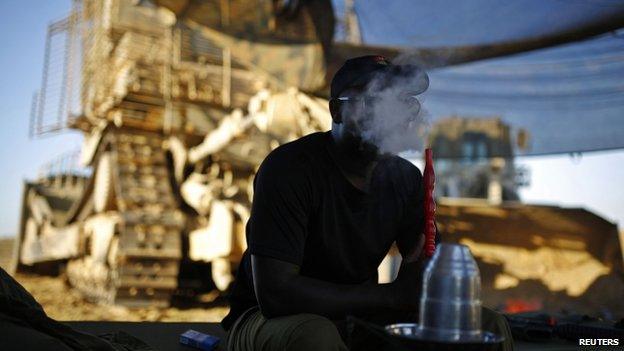

Israel's military equipment - such as this Raz battery - is clear to see along the border

For Dov Hartuv, 78, the Gaza border is so close - only 800m from his home on the Israeli kibbutz of Nahal Oz. And the year 2000 seems so far away.

"My wife and I went on a guided tour of Gaza in 2000 with a Gazan guide," he recalls, with obvious warmth, when we meet in his dusty desolate community which emptied of residents when this latest war began.

I also remember trips to Gaza then when we visited, as Dov did, the airport terminal about which, he said "the Gazans were so proud".

Does he think that kind of relationship with Gaza could ever happen again?

Temporary truce

"Why not?" he replies, without hesitation. "It's just a question of wanting a lasting way to live together."

Damage on the Israeli side of the border is minimal compared to the devastation in Gaza

The jagged skyline across the entire length of the Gaza Strip is visible from Israeli border areas

"I wouldn't call it peace," adds the lanky Israeli of South African origin who has lived on the edge of Gaza for 61 years and did not even leave during this war. "It's about finding a way to let people on each side live their lives."

But along this border now, it is as far away as you can get from peace.

Tanks and troops pulled out of Gaza during the temporary truce, but they are parked just a few kilometres away.

"We can be back in Gaza within an hour if it all collapses," one Israeli soldier says as she saunters across the wide expanse of open ground where armoured vehicles keep rumbling past, throwing up clouds of dust.

'Most frightening thing'

Many soldiers, especially young reservists, express hope that this latest war is now over. Their commanders say the job is done.

Israel says that it has achieved its military objectives in the Gaza Strip

Israel says its prepared to send its tanks currently on the border with Gaza back into the Strip if that is what is required to maintain security

"Without question we achieved our objective," Lt-Col Edam tells me. "We destroyed the tunnels which presented a strategic threat to Israel."

Hamas fighters emerged from one of those tunnels which ended at the edge of Nahal Oz. Five Israeli soldiers died in the fire fight here.

"It was the most frightening thing we've ever seen here," remarks Dov as walk across the dairy farm where hundreds of black and white cows still munch in vast pens, a strange bovine image of calm in the midst of this latest storm.

"No-one can be sure there aren't more tunnels and this is what keeps people from returning," Dov explains."Families with children won't come back until they are sure this ceasefire will last."

Some of the remaining residents also tell us a few houses in the kibbutz were damaged in this latest war.

Temporary truce

But then they suggest it is best not to film them, pointing out damage is minimal compared to the devastation just across the border.

.jpg)

Hundreds of cows still munch in vast pens on the Israeli side of the border, a strange bovine image of calm in the midst of this latest storm

Israel argues that civilian casualties in Gaza are a tragedy of Hamas's own making

Nahal Oz is so close to Gaza that Israel's anti-missile battery, the Iron Dome, cannot intercept rockets that land there. Residents only get a five-second Red Alert warning.

But they are helped, as all Israelis are, by a state-of-the-art radar stationed in southern Israel.

In Hebrew its called the the Raz; in English, it's the MMR - Multi-Mission Radar. We are given access as the first foreign media to film there but strictly forbidden to broadcast the classified data on the screen.

The soldiers bring up the detailed maps of Gaza and Israel that show what the screens looked like the day before the temporary truce - a dense array of arcs tracing the trajectory of rockets launched into Israel and wide circles marking coverage of Israeli drones which constantly whine over Gaza.

Mounting civilian casualties

It is a graphic depiction of what the relationship between Gaza and Israel looks like now.

Israel says that it can send its troops back into Gaza at a moment's notice

Tanks and troops pulled out of Gaza during the temporary truce, but they are parked just a few kilometres away

The Raz tracks where rockets are being fired from, and where they will land. That intelligence feeds into the Iron Dome to help it intercept incoming fire.

It also alerts Israeli citizens to take to their shelters, and allows commanders to take decisions on where to return fire.

On the wall, handwritten letters from Israeli children, with big yellow suns and brightly coloured flowers, thank the soldiers for keeping them safe.

I ask why with such good intelligence, there have still been - according to the UN - repeated strikes on the schools serving as shelters for the many thousands of displaced people in Gaza.

"We don't take those decisions here," one soldier explains, pointing out that the Raz is only one of the tools used by Israeli forces. Then he adds quickly: "But it is clear that, sometimes, rockets are fired from schools, hospitals and other civilian places".

'A tragedy'

As the international outcry grows over Gaza's mounting civilian casualties, this is partly what fuels Israel's diplomatic offensive now.

At the moment we are visiting the Raz, Prime Minister Netanyahu is telling a press conference for foreign journalists in Jerusalem that "every civilian casualty is a tragedy, a tragedy of Hamas's own making".

"This is the first lesson of this war," prominent columnist Ari Shavit tells me when we meet at Tel Aviv harbour. "We must find way a new way to fight Hamas which doesn't mean so many civilian casualties."

As ceasefire talks intensify, so do the arguments in Israel over what kind of arrangements should govern Gaza.

Some are still pushing for Hamas to be crushed once and for all.

Others, including many in the international community, want an expanded role for the Palestinian Authority under President Mahmoud Abbas.

Some in Israel want the armed forces to crush Hamas once and for all

"Many Israelis had been willing to pay a huge price if it meant a final end to the Gaza conflict but there is now a silent majority that now believes it is better to stop, even if the operation did not achieve all its goals," says Mr Shavit, the author of My Promised Land.

He is speaking against an idyllic backdrop of a revolving pink carousel and a few fishermen casting rods into the sea. "People want to return to the beauty of Israeli life, not its horrors."

Gazans also want lives worth living. For them, that means not just an end to this war, but also the end of a seven-year blockade to allow greater movement of goods and people through crossings into Israel and Egypt.

"People don't realise how densely populated and poor Gaza is," remarks Dov Hartuv as we stand at the furthest edge of the kibbutz that he says it is safe to go.

From that vantage point, you can see, in detail, the jagged skyline across the entire length of the Gaza Strip.

Letting people on both sides of this border live their own lives used to be seen as a more achievable goal than reaching a peace deal.

But even reaching that kind of calm seems to get ever more difficult.