Mosul Dam: Why the battle for water matters in Iraq

- Published

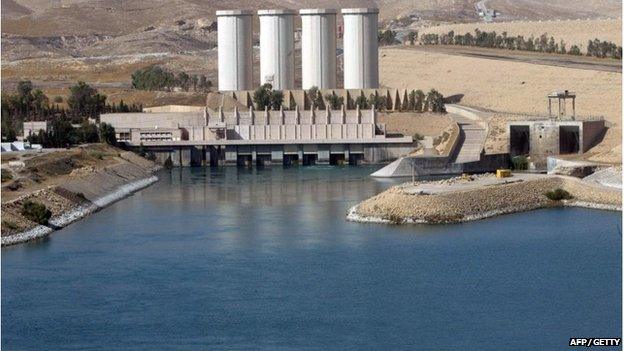

The Mosul dam is the water and electricity lifeline to the 1.7 million residents of Mosul

Whoever controls the Mosul Dam, the largest in Iraq, controls most of the country's water and power resource.

When Saddam Hussein built the dam three decades ago, it was meant to serve as a symbol of his leadership and Iraq's strength.

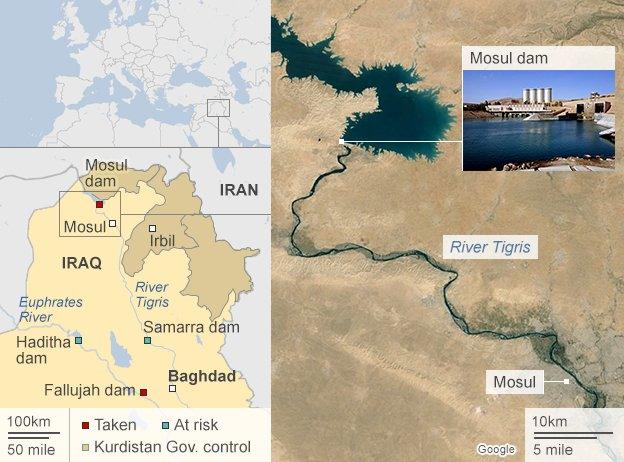

The dam is the latest key strategic battleground in northern Iraq between militants from Islamic State (IS), who took it on 7 August, and Kurdish and Iraqi forces supported by American airpower.

Located on the River Tigris about 50km (30 miles) upstream from the city of Mosul, the dam controls the water and power supply to a large surrounding area in northern Iraq.

Its generators can produce 1010 megawatts of electricity, according to the website of the Iraqi State Commission for Dams and Reservoirs.

The structure also holds back over 12 billion cubic metres of water that are crucial for irrigation in the farming areas of Iraq's western Nineveh province.

Instrument of war

However, since its completion in the 1980s, the dam has required regular maintenance involving injections of cement on areas of leakage.

The US government has invested more than $30m (£17.9m) on monitoring and repairs, working together with Iraqi teams.

The black flags of jihadist group Islamic State flew over the Mosul dam for 10 days before it was recaptured by Kurdish and Iraqi ground forces

In 2007, the then commanding general of US forces in Iraq, David Petraeus, and the then US ambassador to Iraq, Ryan Crocker, warned Iraq's PM Nouri Maliki that the structure was highly dangerous because it was built on unstable soil foundation.

"A catastrophic failure of Mosul dam would result in flooding along the Tigris river all the way to Baghdad," they said in a letter.

"Assuming a worst-case scenario, an instantaneous failure of Mosul dam filled to its maximum operating level could result in a flood wave 20 metres (65.5ft) deep at the city of Mosul," it said.

Writing to Congress, President Obama cited the potentially massive loss of civilian life and the possible threat to the US embassy in Baghdad.

Those dangers, he wrote, were sufficient reasons for deploying air power to support Kurdish forces trying to recapture the dam.

'Method in their madness'

Relief in Washington and Baghdad will only come when IS militants, who have sought control of water resources before, have been stopped from using the dam as an instrument of war.

The deployment of air power by the US in support of Kurdish forces has shown how seriously the White House takes the potential threat posed by IS control of the dam.

The Fallujah dam, in the Nuamiyah area of the city, in Iraq's western Anbar province, fell under IS control in February.

However, the group has so far failed in its attempts to capture the Haditha dam, Iraq's second largest, from the army.

The Tigris River crosses Iraq and Syria at Fishkhabour, where displaced Yazidis have travelled to escape the Islamic State advance

The 8km-long Haditha dam and its hydro-electrical facility, located to the north-west of Baghdad, supply 30% of Iraq's electricity. Securing it was one of the first objectives of US special forces invading Iraq in 2003.

With the Mosul dam in its hands, the concern is that Islamic State could "flood farmland and disrupt drinking water supplies, like it did with a smaller dam near Fallujah this spring," wrote Keith Johnson in an article for Foreign Policy last month.

In May, a flood displaced an estimated 40,000 people between Fallujah and Abu Ghraib.

Earlier this month, IS militants reportedly closed eight of the Fallujah dam's 10 lock gates that control the river flow, flooding land up the Euphrates river and reducing water levels in Iraq's southern provinces, through which the river passes.

Many families were forced from their homes and troops were prevented from deploying, Iraqi security officials said.

Reports say the militants have now re-opened five of the dam's gates to relieve some pressure, fearing their strategy might backfire if their stronghold of Fallujah flooded.

Key Iraqi dams taken or at risk of being taken by Islamic State

In the days after they took over the Mosul dam, militants were reportedly blackmailing frightened workers to either keep the facility going or lose their pay.

Analysts fear the Islamic State could now use the dam as leverage against the new Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, by holding on to the territory around it in return for continued water and power supply.

The group already controls other key national assets - several oil and gas fields in western Iraq and Syria.

"These extremists are not just mad," says Salman Shaikh, director of the Brookings Institution's Doha Centre in Qatar.

"There's a method in their madness. They've managed to amass cash and natural resources, both oil and water, the two most important things. And of course, they're going to use those as a way of continuing to grow and strengthen."