Iraq mission creep: What are the risks?

- Published

The Peshmerga are fighting Islamic State in the north of Iraq

Things are moving very fast in Iraq. Three months ago the country barely got a mention in Cabinet meetings in Whitehall. British forces left in 2011, after 8 troubled years there, and even the Americans had only a very limited presence. Iraq was essentially being left to itself.

Today, following the lightning land-grab by the jihadists of Islamic State (IS) who now control roughly a third of Iraq and much of north-east Syria, the West is being drawn reluctantly but inexorably back into the region.

There are daily multiple sorties by US F/A-18 Hornet fighter bombers flying off a US Navy aircraft carrier in the Gulf, some resulting in airstrikes on advancing Islamic State forces that have threatened civilian refugees and the Kurdish capital of Irbil.

Unmanned US drones are in the air gathering a constant stream of intelligence which is being fed back to a US-manned operations centre in Baghdad and then shared with America's allies.

There are close to 1,000 US military advisors in Iraq, including Special Operations forces, divided between Baghdad and Kurdistan and the CIA is believed to be running an operation to supply Kurdish forces, the Peshmerga, with arms and ammunition.

France and Germany both say they will send military equipment to help the Kurds defend themselves. RAF C130 Hercules transport planes have been dropping aid to civilians fleeing from the onslaught of IS, previously known as Isis, the Islamic State in Iraq and Sham (meaning Greater Syria).

Hundreds of Yazidis have fled the violence of Islamic State

RAF Chinook helicopters are on their way to the region. Australia is sending two C130 airplanes of its own and is considering joining Washington in combat operations against the IS. And so the list goes on.

But while the case for intervention on humanitarian grounds to save the lives of thousands of fleeing refugees is overwhelming, there is now the risk of what is known as "mission creep"; of a small, narrowly defined operation ballooning out of control, sucking in Western countries into a lengthy conflict with no clear exit.

Already there are calls from some politicians - including the former Defence Secretary Liam Fox - for Britain to join America in a combat role.

Analysts point out that however many refugees are escorted to safety, the fact remains that they have lost their homes to an invasive, extremist force that remains in place and will continue to threaten the whole region for as long as it exists.

Others contend that the West has already done enough damage in Iraq by invading in 2003, on the false pretext of finding Saddam Hussein's non-existent "Weapons of Mass Destruction", and it should now leave the area well alone.

So, just what are the risks of mission creep in Iraq?

Shifting objectives

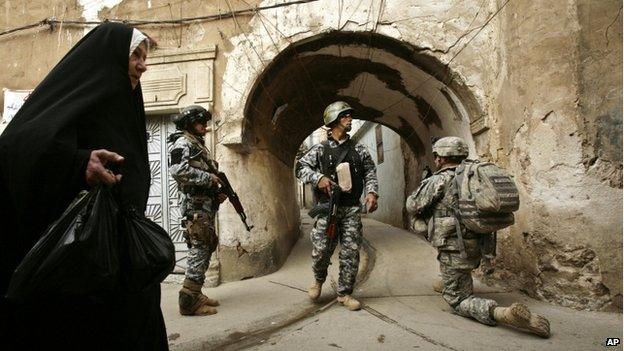

US troops were present in Iraq from 2003 until 2011

Today the West's objectives in Iraq are relatively clear: save as many refugees as possible from slaughter by IS jihadists, push back IS forces from the Kurdish capital Irbil and support the elected government in Baghdad.

Western politicians are fond of saying "there will be no boots on the ground" but in practice there are already growing numbers of US military personnel deployed to Iraq behind the scenes.

What if advice and air power alone are not enough to prevent the IS from taking more towns in Iraq and Kurdistan? What if Baghdad itself or the cities of Kirkuk or Irbil look threatened?

The risk of a mission's objectives shifting away from their original confines increase substantially when you are not in control of events on the ground.

Civilian casualties

Around 5,500 civilians have been killed in the last six months, according to the UN

When US warplanes or drones fire precision-guided missiles at IS positions exposed in the open on the flat plains of northern Iraq and Kurdistan, there is little risk of causing civilian casualties. But the vast majority of IS jihadists are firmly embedded in residential areas like Mosul in Iraq and Raqqa in Syria.

Already Iraqi government airstrikes around Mosul have led to reports of civilian casualties, leading to accusations of a Shia-dominated government attacking Sunni civilians.

The West has already been blamed for the deadly violence that followed the US-led invasion of 2003, so its leaders will not want to be accused of having more blood on their hands.

Military casualties

The Peshmerga have received help from recent US airstrikes on IS positions

The nightmare scenario for Washington and its allies is the downing of a warplane and the capture alive of its crew as hostages. An organisation that has already made extensive use of social media to broadcast its numerous beheadings, crucifixions and amputations can be expected to take maximum advantage of such a prize for propaganda and recruitment.

Today opinion polls in the UK show considerably more public support for military action against IS than there was for airstrikes against Syrian regime forces last year. But that support could soon wither away if those countries coming to the aid of Baghdad and Irbil started taking serious casualties.

Intelligence on exactly what usable weapons IS have in their arsenals is incomplete and military planners will be making their calculations based on a worse-case scenario - that IS have some capability to shoot planes out of the sky.

'Blowback' in the UK

Three Britons appeared in an Islamic State recruitment video in June

To some degree, this risk already exists. Around 500 UK nationals are estimated to have gone to Syria to become jihadists with most joining Islamic State, which straddles both countries, Syria and Iraq.

At least half are believed to have returned to Britain. Police counter-terrorism officials and MI5 have made contingency plans that assume that with no sign of an end to the conflicts in Syria and Iraq, the number of returning British jihadists will only grow year by year, with a small minority at risk of committing acts of violence in the UK.

But that risk can rise dramatically when there is a compelling rallying cry for revenge by online jihadists. Once British forces become linked to the deaths of "martyred" Islamic State fighters then the risk of "blowback" to Britain and revenge attacks in the UK will inevitably increase.