Iraq crisis: Gauging Obama's strategic goal

- Published

The US has been reluctant to get sucked back into Iraq on a military level

All three of President Barack Obama's predecessors in the White House were involved in one way or another with military conflicts in Iraq. Now, having set out his stall as the president who would end Washington's foreign interventions, Mr Obama has a new Iraqi conflict of his own.

True, for now, the US role seems limited and circumscribed. Mr Obama has made it clear that it is up to the Iraqis to do the fighting. There will be no US "boots on the ground", at least in terms of combat troops.

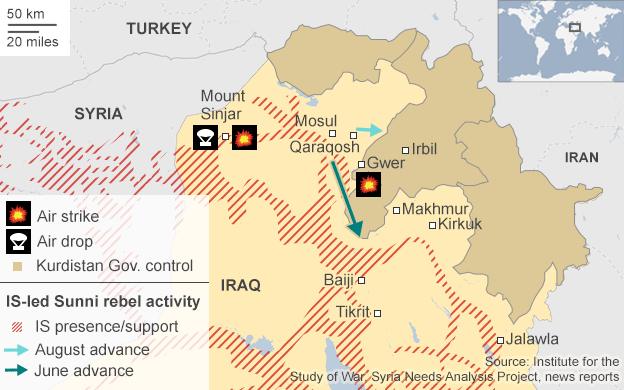

A further 130-strong US assessment team of military advisers has been despatched to Irbil - in addition to the US trainers and liaison people who are already there. But the aim is to bolster the Kurdish Peshmerga fighters to enable them to hold the line against the advancing Islamic State (IS) tide.

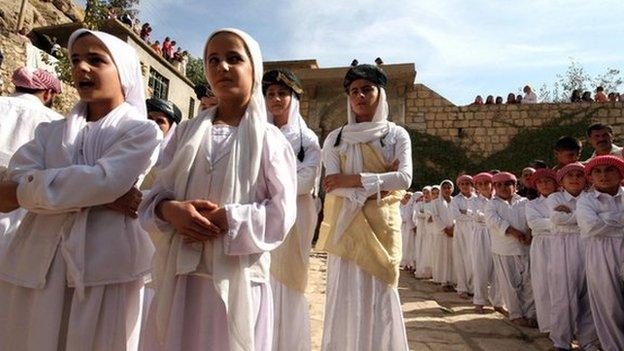

The humanitarian crisis afflicting Iraqi minorities - the Christians and the ancient Kurdish Yazidi sect - has formed the ostensible reason for American involvement. Accordingly the US action has been as much humanitarian as military.

Tens of thousands of Yazidis have fled in the face of the Islamic State advance

Indeed the number of actual air strikes on IS vehicles and positions has been small - enough to send a clear warning that an advance on Irbil would bring much heavier US action.

For now, at least on this front, the US demonstration may have contained the pressure on the Peshmerga, though it has clearly done nothing to put the IS advance into reverse.

Fanned by factionalism

This, then, raises the most fundamental question about Mr Obama's war: what is its strategic goal?

Is it to try to defeat IS - a group that holds a huge swathe of territory in both Syria and Iraq and one that is already being hailed as the next great strategic threat to the region and beyond ?

If so, then according to Mr Obama's critics, US action has been both too little and too late.

But there are significant constraints on US action and Mr Obama's caution may indeed be well advised.

The message coming from Washington is that Iraqis must do the heavy lifting here themselves. The reason they cannot is seen in the West as being due to the disastrous factionalism pursued by the Shia Prime Minister Nouri Maliki.

Giving Kurdish fighters too many weapons could create problems down the line for Iraq

His administration has undermined confidence in the central government in Baghdad. But worse, his favouritism and sectarian approach has served to hollow out the US-trained Iraqi military, which, when faced with ruthless IS, has frequently melted away, its troops abandoning their equipment.

This equipment has served to reinforce the jihadists, helping them to out-gun the Kurdish fighters in the north.

Significant US help has been made conditional on achieving a more inclusive government in Baghdad - implying Mr Maliki's departure. He now does appear to be on the way out.

But the humanitarian crisis and the threat to Washington's long-standing ally, the Kurds, forced Mr Obama's hand.

But the message from Washington remains that US action will be limited until significant changes are seen in Baghdad.

Much, too, has been made of a second constraint; a desire not to arm the Kurds to such an extent that they could forcefully break away from Iraq altogether.

Elements of civil war

Washington remains wedded to the current status quo in Iraq even as the centrifugal forces there appear to be growing. The Kurds have carved out a remarkable degree of autonomy over many years.

To a large extent they have a successful "country" in all but name. But they have shown only limited desire to expand the area they control. Arming them now is an urgent priority so that they can defend their lengthy border against the IS forces.

The US, France, the Czech Republic and Jordan have all pitched in to promise arms or equipment of various kinds and more is likely to follow. But so far few details have been given as to exactly what weaponry is involved.

While air strikes and air drops have been authorised, no combat troops are in the offing

A third constraint is probably even more significant and that is the make-up of the IS coalition.

On the map it seems to dominate a great swathe of territory - although of course much of this is simply empty space. It is not a huge organisation, though well-organised and well-financed.

Its success is in part due to the relationships it has formed with local Sunni tribes and factions who themselves have been alienated by the Maliki regime. In this sense this battle is not simply, as many in the West would have it, a struggle against jihadism, but it also has elements of an Iraqi civil war.

Many of these may well be groups that the US won over in the so-called "awakening" when it rallied Sunni tribes to the Iraqi state against Jihadist extremists during the US occupation.

Bombing Iraqi Sunni militias is hardly going to be a good way of reconstituting some kind of coherent and inclusive Iraqi state.

If there can be genuine political change at the centre or maybe if they become alienated by the brutality of IS rule, then perhaps they can again be rallied to Baghdad.

High risk

This, though, is a high-risk strategy for the Americans. IS is fighting on multiple fronts and in recent days it has made some gains in the direction of Baghdad.

What would the US do if the Iraqi capital again appeared to be under threat or if there was a further military collapse on the part of government forces ?

The danger for Mr Obama is that time is not necessarily on his side.

The direction of political change in Baghdad appears positive for Washington if Mr Maliki really is on the way out. Even his Iranian allies seem to have tired of him.

But a new prime minister will only be a beginning. It is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for change at the centre.

Even a more inclusive government will take time to have an effect. And the performance of the shaken Iraqi military is not going to change overnight either.

The danger is that it will be the IS actions that determine the pace and scale of US intervention.

Mr Obama must also contend with the broader strategic picture.

IS is a transnational organisation in the sense that it is fighting in both Iraq and Syria. Indeed the geographical ambitions of its caliphate may be even broader. It has taken on the Lebanese army in the border region and potentially threatens Jordan too.

The US needs to establish a broader coalition in the region to contain the IS advance.

And in this light it cannot avoid thinking again about Syria.

Syria, after all, provided the launch pad for IS. And the failure to halt its growth there meant that it was able to export its violence across the border into Iraq.

- Published7 August 2014

- Published21 July 2014