Islamic State: Radical shifts needed to combat threat

- Published

US involvement against IS has so far taken the form of air strikes supporting Kurdish fighters on the ground

US defence chiefs have spelled out their conviction that a complex long-term war will be needed, with intervention in both Syria and Iraq, if Islamic State's "caliphate" is to be uprooted from those two countries.

But there are huge and separate complexes of problems in both those countries that will have to be resolved if that is to happen.

Many political setups, relationships and alliances will have to change.

That will take time, probably a lot of time, and with every day that passes, the problem will grow bigger as the Islamic State (IS) militants become more entrenched.

They are already a far more formidable foe than their original disapproving parent organisation al-Qaeda ever was, as the US military chiefs acknowledged.

IS rules large swathes of territory in both countries, controlling and administering towns and cities with a collective population of millions.

It is immensely rich and well-armed, achieving an independence in both arms and money that put it beyond the influence of prior outside sponsors.

Its fighters, joined by thousands of new recruits from places like Mosul where money holds sway among unemployed youth, have shown in battle not only a fanatical ferocity and mastery of the advanced weaponry they have acquired, but also impressive tactical and strategic skills, running offensives in widely separate locations at the same time.

Allies needed

The fighting has lead to a humanitarian crisis, with thousands of Iraqis displaced

The Western powers are obviously reluctant to send ground forces into the fray, for sound historical reasons.

It's not just that their publics are averse to the notion of body bags coming home in increasing numbers in what could be an open-ended commitment.

The Pentagon leaders were also clearly aware that US involvement on the ground could aggravate the politics of the situation and prove severely counter-productive.

Simply carrying out air strikes alone might achieve some tactical goals, but they would have no chance of settling the conflict and uprooting the IS.

So air strikes will have to be co-ordinated with advances by local allied forces on the ground.

That is already happening in northern Iraq where, with the help of US air strikes, the mainly Kurdish peshmerga forces have begun to roll back the lightning advances made by the IS radicals with their surprise attack on Kurdistan two weeks ago.

But the Kurdish case is comparatively simple. The Kurds have been allied to the West for decades and are natural partners.

That same template cannot, however, be simply transferred to the rest of Iraq and extended to Syria.

Strange bedfellows

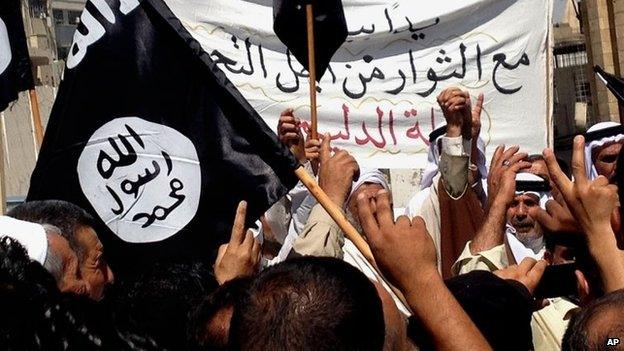

IS has been able to capitalise on the wave of Iraqi Sunni discontent with the country's authorities

In Iraq, a strong strand in the conflict that is raging daily in many parts of the country is a sectarian civil war between a Shia-dominated establishment in Baghdad and Iraqi Sunnis alienated by the divisive policies of outgoing Prime Minister Nouri Maliki, who remains as caretaker until his successor Haidar al-Abadi forms a new government.

The IS militants have been able to ride a wave of Iraqi Sunni resentment against the Baghdad government.

Sunni rebels with understandable grievances are mixed up with the IS radicals, so if the US were to join battle against the latter, they would risk outraging the Iraqi Sunnis yet further, and being seen as backing one side in the civil war.

That's why the Americans are eager to see the emergence of a fully inclusive new Iraqi government that would redress the balance and form a platform for a unified national drive against IS.

That is a tall order. Apart from Shia resistance to Sunni demands for empowerment, there are many different currents of Sunni opinion with varying ideas about what power-sharing formula would satisfy them - devolution, autonomy, self-security, and so on.

The idea is to pull the Sunni rug from under the feet of the IS, isolating and hitting the latter with a coalition of forces that would involve Iraqi Sunni nationalist fighters from the tribes and former Iraqi army units, the Kurdish peshmerga - if they can overcome their reluctance to move into Sunni-majority areas - and perhaps even regional forces from neighbouring countries, possibly including Iran.

Hard to imagine, but acute new crises produce strange bedfellows.

Assad rehabilitated?

PKK fighters have been on the front line together with Kurdish forces in Iraq

Already in northern Iraq, the Turkish Kurdish PKK has been involved in the drive against the IS, alongside peshmerga forces from the dominant Iraqi Kurdish party, the KDP, with which it is politically strongly at odds.

And already in northern Syria, the PKK's Syrian Kurdish offshoot the PYD and its military affiliate the YPG have broken the myth of IS invincibility by standing up to the Islamist radicals for months, with very little outside help and no air cover.

So the US in Iraq is already tacitly teamed up on the same side as the PKK, officially regarded by Washington itself and by its Nato ally Turkey as a terrorist organisation.

What next? A similar convergence of US interests with Iran and satellite Shia militias such as Hezbollah?

Stranger things have happened, and they may get stranger yet, given the magnitude of the IS challenge.

The same goes for Syria, where the government is limbering up to gain international rehabilitation by claiming a place as partner in the campaign against a radical presence which it has been accused by many of enabling and encouraging to take root, in order to tar the entire Syrian opposition with the "terrorist" brush.

Is the perceived threat from IS so great that the Western powers will forget their opposition to Bashar al-Assad, team up with him, and pressure their opposition allies to set aside their own raison d'etre and turn full time against the radicals alongside government forces?

Simply carrying out air strikes in Syria will achieve little, and would also be hard to do without collaborating with, or destroying, the regime's anti-air defences.

It's all hard to imagine. But until recently, the current nightmare was also unimaginable. Many radical realignments, unpalatable though they may seem, will have to come about if the challenge is to be seriously met.