Islamic State: Where does jihadist group get its support?

- Published

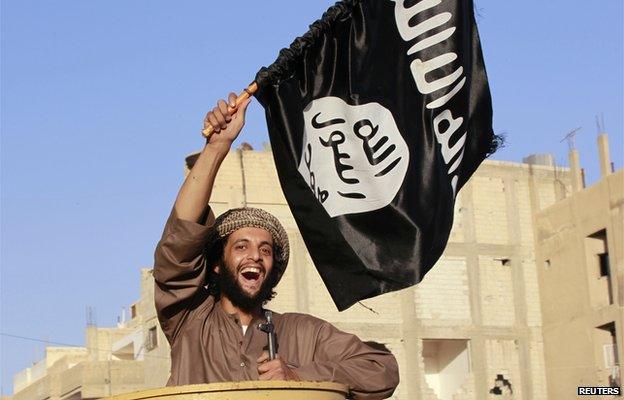

Islamic State outperformed all other militant rebel groups in Syria and continues to claim ground

Many Gulf states have been accused of funding Islamic State (IS) extremists in Iraq and Syria.

But as Michael Stephens, director of the Royal United Services Institute in Qatar, explains, not all is clear-cut in war.

Much has been written about the support Islamic State (IS) has received from donors and sympathisers, particularly in the wealthy Gulf States.

Indeed the accusation I hear most from those fighting IS in Iraq and Syria is that Qatar, Turkey and Saudi Arabia are solely responsible for the group's existence.

But the truth is a little more complex and needs some exploring.

It is true that some wealthy individuals from the Gulf have funded extremist groups in Syria, many taking bags of cash to Turkey and simply handing over millions of dollars at a time.

This was an extremely common practice in 2012 and 2013 but has since diminished and is at most only a tiny percentage of the total income that flows into Islamic State coffers in 2014.

It is also true that Saudi Arabia and Qatar, believing that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad would soon fall and that Sunni political Islam was a true vehicle for their political goals, funded groups that had strongly Islamist credentials.

Liwa al-Tawhid, Ahrar al-Sham, Jaish al-Islam were just such groups, all holding tenuous links to the "bad guy" of the time - the al-Nusra Front, al-Qaeda's wing in Syria.

The new emir of Qatar, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani with French President Francois Hollande

Saudi Arabia has been accused of funding Islamists under the banner of IS, an accusation it staunchly denies

Gulf funds have flowed to opposition groups since the early days of the uprising against Bashar al-Assad

Qatar especially attracted criticism for its cloudy links to the group.

Turkey for its part operated a highly questionable policy of border enforcement in which weapons and money flooded into Syria, with Qatari and Saudi backing.

All had thought that this would facilitate the end of Mr Assad's regime and the reordering of Syria into a Sunni power, breaking Shia Iran's link to the Mediterranean.

Yet as IS began its seemingly unstoppable rise in 2013, these groups were either swept away by it, or deciding it was better to join the winning team, simply defected bringing their weapons and money with them.

Only al-Nusra has really held firm, managing a tenuous alliance with its more radical cousin, but even so it is estimated that at least 3,000 fighters from al-Nusra swapped their allegiance during this time.

So has Qatar funded Islamic State? Directly, the answer is no. Indirectly, a combination of shoddy policy and naivety has led to Qatar-funded weapons and money making their way into the hands of IS.

Saudi Arabia likewise is innocent of a direct state policy to fund the group, but as with Qatar its determination to remove Mr Assad has led to serious mistakes in its choice of allies.

Both countries must undertake some soul searching at this point, although it is doubtful that any such introspection will be admitted in public.

Light years ahead

But there are deeper issues here; religious ties and sympathy for a group that both acts explicitly against Shia Iran's interests in the region and has the tacit support of more people in the Gulf than many would care to admit.

The horrific acts committed by IS are difficult for anybody to support, but its goal of establishing a caliphate is certainly attractive in some corners of Islamic thought.

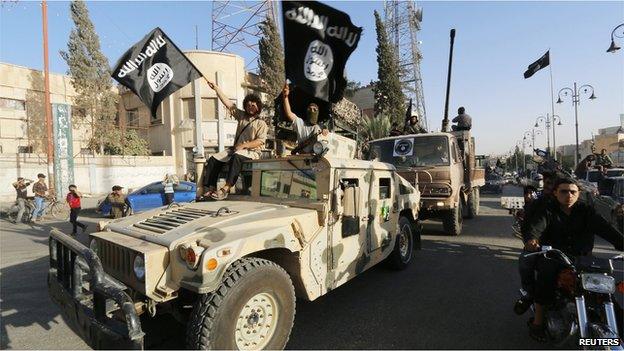

The goal of IS militants is to create an independent Islamic State stretching from Iraq across to the Levant

Many of those who supported the goal have already found their way to Syria and have fought and died for Islamic State and other groups. Others express support more passively and will continue to do so for many years.

The pull of IS, a group that has outperformed all others in combat and put into place a slick media campaign in dozens of languages to attract young men and women to its cause, has proven highly successful.

In every activity - from fighting, to organisation and hierarchy, to media messaging - IS is light years ahead of the assorted motley crew of opposition factions operating in the region.

'War economy'

Islamic State has put in place what appear to be the beginnings of quasi-state structures - ministries, law courts and even a rudimentary taxation system, which incidentally asks for far less than what was paid by citizens of Mr Assad's Syria.

IS has displayed a consistent pattern since it first began to take territory in early 2013.

Upon taking control of a town it quickly secures the water, flour and hydrocarbon resources of the area, centralising distribution and thereby making the local population dependent on it for survival.

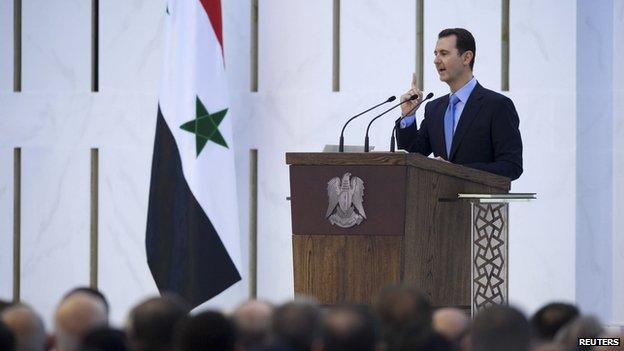

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad is accused of doing business with Islamic State in Syria

Dependency and support are not the same thing, and it is impossible to quantify how many of Islamic State's "citizens" are willing partners in its project or simply acquiescing to its rule out of a need for stability or fear of punishment.

To understand how the Islamic State economy functions is to delve into a murky world of middlemen and shady business dealings, in which "loyal ideologues" on differing sides spot business opportunities and pounce upon them.

IS exports about 9,000 barrels of oil per day at prices ranging from about $25-$45 (£15-£27).

Some of this goes to Kurdish middlemen up towards Turkey, some goes for domestic IS consumption and some goes to the Assad regime, which in turn sells weapons back to the group.

"It is a traditional war economy," notes Jamestown analyst Wladimir van Wilgenburg.

Indeed, the dodgy dealings and strange alliances are beginning to look very similar to events that occurred during the Lebanese civil war, when feuding war lords would similarly fight and do business with each other.

The point is that Islamic State is essentially self-financing; it cannot be isolated and cut off from the world because it is intimately tied into regional stability in a way that benefits not only itself, but also the people it fights.

The larger question of course is whether such an integral pillar of the region (albeit shockingly violent and extreme) can be defeated.

Without Western military intervention it is unlikely. Although Sunni tribes in Iraq ponder their allegiances to the group, they do not have the firepower or finances necessary to topple IS and neither does the Iraqi army nor its Syrian counterpart.

Michael Stephens is Director of the Royal United Services Institute, Qatar, and is currently in Irbil