Will Obama's anti-IS strategy work?

- Published

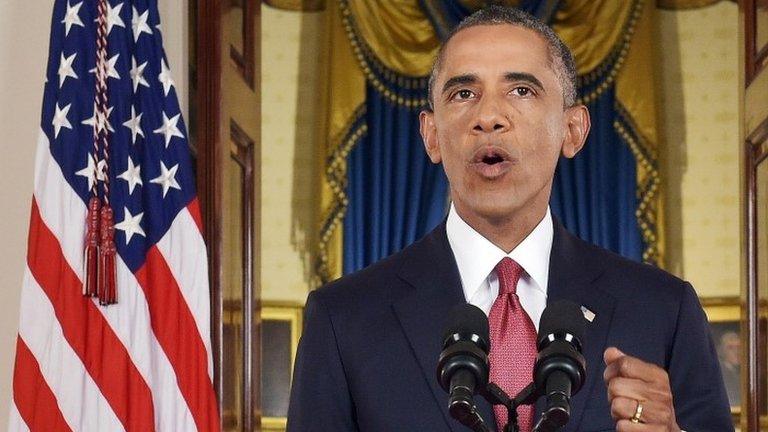

President Obama's four-point plan includes air strikes against Islamic State

US President Barack Obama was clear. Islamic State - or Isil as he calls it - represents not just a threat to Washington's friends and interests in the Middle East. It could potentially become a threat to the American homeland itself.

Mr Obama is calling for concerted action: a wide array of countries have already joined the struggle against IS.

Indeed, the Islamic State threat has already begun to break down some of the region's long-standing divisions, with Iran and Saudi Arabia - standard-bearers of the Shia and Sunni constituencies respectively - both eager to assist the Iraqi government.

For a US president who was charged by many during the Libya war of failing to live up to America's responsibilities and "leading from behind", Mr Obama on Wednesday offered a classic re-statement of the US responsibility to lead - America's "endless blessings", he noted, "bestow an enduring burden".

"As Americans", he said, "we welcome our responsibility to lead."

'Tip of spear'

That will be well received in a number of Middle Eastern capitals where US vacillation - especially the collective failure of the Obama administration and Congress to act over Syria - greatly damaged America's standing.

President Obama: "We will degrade and ultimately destroy" IS

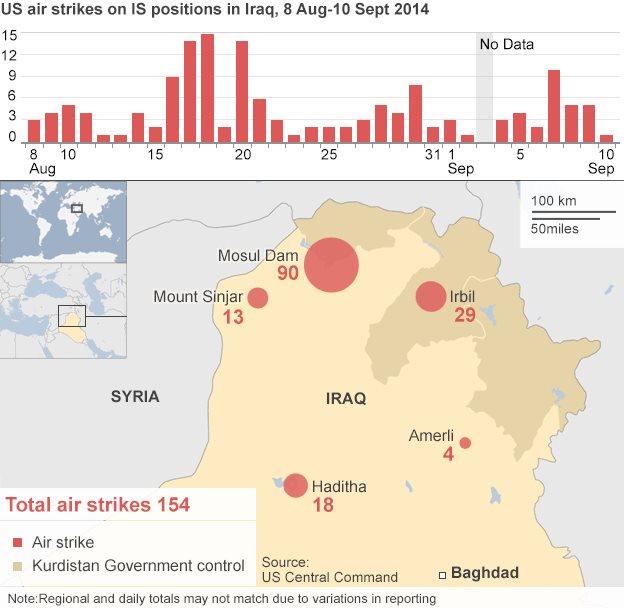

Far from not having a strategy as he appeared to indicate only a short while ago, Mr Obama's four-point plan of air strikes, material and technical support for those fighting on the ground, counter-terrorism activities and humanitarian assistance together build very much on the policies pursued so far in Iraq.

Indeed, it was set out eloquently in a New York Times opinion article, external by US Secretary of State John Kerry on the 29 August. This has to some extent halted the IS advance. Now Mr Obama wants to put it into retreat.

This is a policy that is on the face of things both practical and politically doable, in the sense that it can muster broad support both at home and abroad.

But can it work?

It is a policy that can only go so far. Everything depends upon the effectiveness of the coalition that is formed and its enduring qualities.

There will be a lot of attention focussed on just who will join the US in actually conducting air strikes. But this - to use a phrase - is only the tip of the spear. Others must do their part.

Can countries like Saudi Arabia and Qatar - friends of Washington - do everything they must to limit local funding for IS?

Can Turkey do more to prevent willing fighters crossing into Syria to volunteer to fight for Islamic State?

And above all can the differences between key players that have been subdued by the rise of IS be contained in the medium-term to give this strategy time to bear fruit?

Or after some initial air strikes will things in due course simply revert to "normal", and the old, obstructive regional enmities return?

It should be remembered, for example, that if the nuclear negotiations involving the US, Iran and others turn sour, this too could damage the "objective" alliance between Washington and Tehran.

Military risks

Of course, the greatest tests of this new strategy will come in Iraq and Syria themselves.

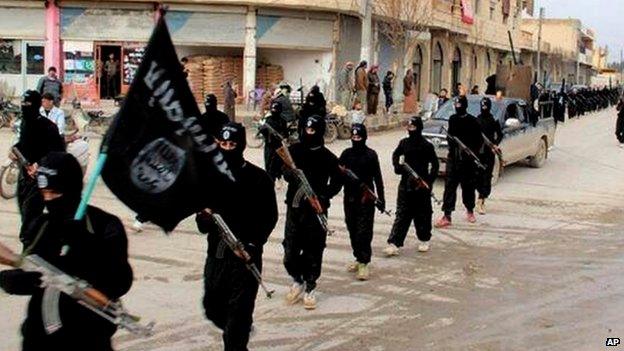

IS fighters have seized large swathes of territory in Syria and Iraq

Iraq's new government has paved the way for more extensive US military action. Challenges, though, remain in both the political and military sphere.

The political reform process is in its infancy. The new government is not fully formed. It has everything still to do to convince the Sunni minority that its future is secure within Iraq as presently conceived.

Key sections of Iraq's US-trained military simply fell apart in the face of the IS onslaught. Mr Obama talks about rebuilding this force. A further 475 US trainers and advisers will be despatched to Iraq. But both establishing some more equitable governance and a more effective army will take time.

It is in Syria that Mr Obama's policy faces its greatest test.

In deciding to extend air strikes to include the IS infrastructure in Syria, Mr Obama is bowing to the inevitable. It makes no sense to allow Islamic State a safe haven there.

This strategy involves military risks. But the judgement may be that the deployment pattern of Syrian air defences, US technical advantages, and the fact that the Syrian regime is equally threatened by IS may reduce some of the dangers to US pilots if manned aircraft are used as well as drones.

Of course, in striking against an enemy of Mr Assad the danger is that the US plan simply helps to perpetuate his rule.

That is where US training and arming for the Free Syrian Army comes in. But this may be a bus that has already departed. It is by no means clear that this fractious organisation really can become a credible fighting force and again - if it is to do so - it will take time.

Strange bedfellows

There is also a curious lack of strategic vision in all of this.

Is the assumption that the departure of Syrian President Assad would leave Syria at peace with itself where IS could find no haven?

Many analysts fear that - bad though he is - Mr Assad's departure could unleash further chaos, potentially massacres of his Alawite minority and a stepped-up struggle among competing groups for control.

What is needed more than ever is a clear strategic sense of what the end-game in Syria should be - one shared by the key regional players along with Washington.

Indeed, there is a broader strategic issue here as well which goes to the heart of the region's problems.

The rise of Islamic State and its control of a swathe of territory in Syria and Iraq is in part a product of the upheavals prompted by the so-called "Arab Spring", as is renewed military control in Egypt and the continuing and unaddressed desire of many in the Arab world for more open and democratic societies.

Islamic State in this sense is a symptom of the region's malaise and it threatens countries and governments many of whom are far from democratic themselves.

This is the coalition with which Mr Obama has to work. Adversity does indeed make strange bedfellows.

- Published11 September 2014

- Published11 September 2014