Yemen: Fragility underlies UN-backed peace deal

- Published

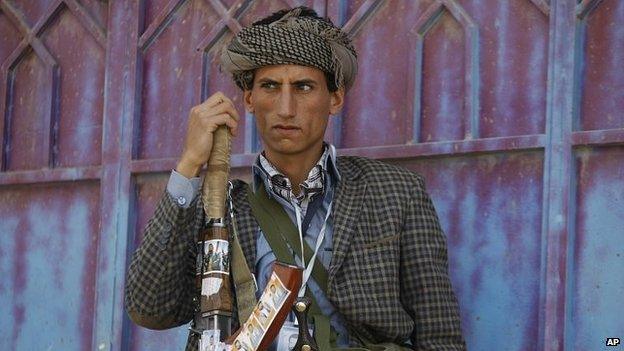

The Shia Houthi rebels managed to rout pro-government forces in the capital, Sanaa

The deadliest days the Yemeni capital has seen since the 2011 uprising that ousted long-time President Ali Abdullah Saleh came to an end on Sunday, with a UN-brokered deal, but whether the accord can deliver long-term peace remains an open question.

The weekend's events capped a series of gains by the minority Zaidi Shia, known as Houthi, who expanded beyond their northern stronghold of Saada in the wake of the 2011 revolt.

Ali Abdullah Saleh had waged six brutal offensives against the Houthis, and they sought to oust the former president's varied allies-turned-adversaries in the Sunni Islamist movement, Islah.

Two key targets were the powerful General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar and his loyalists, and the (unrelated) al-Ahmar family, sons of one of Yemen's most powerful tribal leaders, who died in 2007.

The Houthis exploited widespread resentment of these leaders' long monopolisation of power in Yemen's far north.

With the help of allied tribesmen, they routed such once seemingly invincible figures, with a series of victories which saw them creeping closer and closer to the capital, Sanaa - already the home of many Houthi supporters.

Army 'collusion'

The catalyst for the outbreak of fighting this month was the government's botched roll-out of the removal of fuel subsidies.

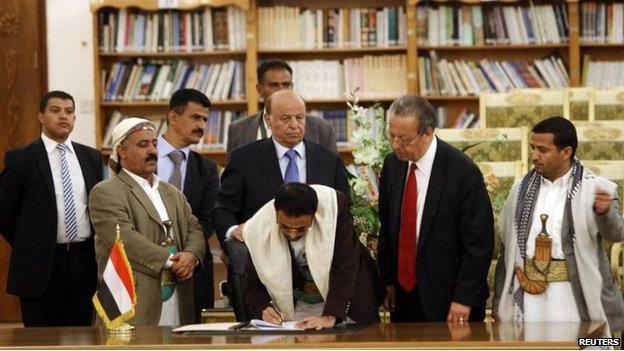

The peace deal will see the formation of a more inclusive government

The deeply unpopular move in an impoverished country spurred the Houthis to call for popular protests - including sit-ins at strategic locations - to get the subsidies' removal reversed, and to replace Yemen's increasingly disliked unity cabinet.

The situation turned violent in the capital, which erupted in fighting between Houthi rebels and Yemeni troops largely aligned with Gen Mohsen.

For the Houthis, it was another victory. The peace agreement was inked after their fighters managed to seize apparent control over a series of key government buildings.

The ease with which they were able to do so underlines the apparent collusion of much of the Yemeni Armed Forces, which remain riddled with division despite the efforts President Saleh's successor, Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, has made towards restructuring the military since coming to power in a one-man election in February 2012.

The peace agreement is, in its essence, a recognition of the Houthis' place in Yemen's political mainstream.

They will be granted a significant amount of power in forming the new government and have gained key concessions with regards to the subsidy removal.

Notably, Houthi representatives declined to sign an annex to the agreement including provisions aimed at securing their fighters' pullout from areas north of Sanaa.

Transcending roots

Regardless, the situation on the ground remains muddled at best.

Armed Houthi fighters continue to man checkpoints in the city and have taken aim at the homes of Islah-aligned figures.

Yemen has been wracked by political instability for years

It remains to be seen how Islah - and for that matter, more radical Sunni Islamists - will react.

An Islah representative did sign the deal, and Houthi spokesmen have said their fight is not with the party as a whole, but with certain figures - most notably, Gen Mohsen, who remains at large.

For its part, the Yemen-based al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) is likely to take aim at the group's apparent ascendance on sectarian grounds.

That said, viewing recent events in Yemen through the prism of sectarianism is deeply misleading, even if the Houthis are largely followers of Zaidism, a northern Yemeni brand of Shia Islam, and their adversaries are overwhelmingly Sunni Islamists.

The Houthis' biggest achievement has been to transcend their roots in the mountains of the devoutly Zaidi far north to position themselves as a national movement.

Notably, the Houthis' ties with Iran notwithstanding, the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) has issued a statement welcoming the peace agreement.

The Houthis themselves acknowledge that they have received political and media support from Iran, while their adversaries claim that they receive Iranian arms and funding, something that has long raised the suspicions of Yemen's Gulf neighbours.

The formal legitimisation of the acerbically anti-American Houthis could very well fuel shifts in the country's foreign policy, and the group has continued to criticise Western interventions in Yemen.

On the whole, however, Yemen's ultimate path remains as unclear as ever: what is quite clear is that things have changed, but the outcome is yet to unfold.

And while most Yemenis celebrated the signing of a peace accord, many worry that the continuing tensions in the capital are only a sign of things to come.

Adam Baron is a London-based writer and political analyst. He was based in Yemen from 2011-2014.

- Published9 September 2014

- Published20 September 2014

- Published21 September 2014

- Published20 September 2014

- Published13 February 2024