Islamic State: Unlikely alliances forming in fight against threat

- Published

This week the United States will use meetings on the margins of the UN General Assembly to finalise its coalition for fighting Islamic State (IS) in Iraq and Syria.

The White House has spoken of rallying 40 countries to the cause, but since this planned group cuts across the Sunni/Shia divide, as well as harnessing long-standing Middle East rivals, many have asked whether it's really possible.

Iran's official Al Alam channel mocked the coalition in an editorial as "a mile wide, an inch deep".

Ghassan Salame, a former Lebanese minister, noted a couple of days ago that "when a disparate set of countries agrees to fight a common enemy, something fishy's going on".

Variously named foe

So Saudi Arabia is meant to back the new government in Iraq even though it's Shia dominated and widely seen as oppressive of Sunnis, the sect which the Saudis regard themselves as protectors of.

Qatar, which has pitted itself against both Saudi Arabia and Iran in the Syrian civil war, is meant to do something meaningful too.

They can't even agree what to call their enemy.

Most reject the militants' own term, Islamic State, adopting Isis (Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham or Syria) instead.

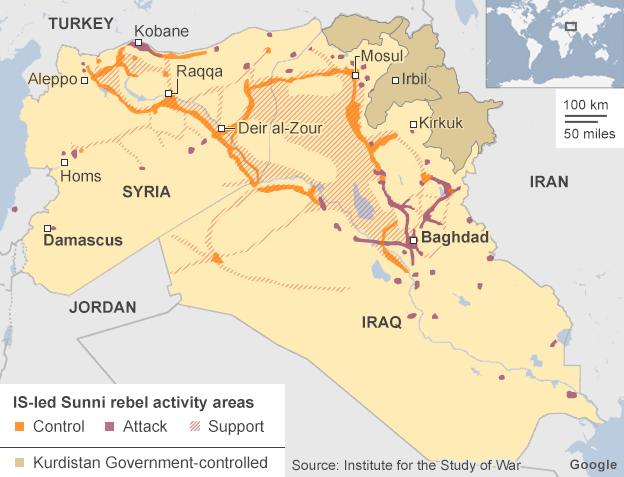

An attempt to retake places like Mosul from IS could be some way off

The US currently favours Isil (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) and France has gone for Da'esh, which is actually the Arabic acronym of Isis and as such is much used in the region.

However unlikely such co-operation against this variously named foe may seem, it is not unprecedented.

The coalition against Saddam Hussein's Iraq, assembled after he invaded Kuwait in 1990, prompted some remarkable alliances.

The common factor between 1990 and now is that the actions of IS threaten the entire system of states in the region.

And whatever the raging against the boundaries or entities imposed by the colonial powers, Arab leaderships are quite determined to defend them in a situation like 1990 or this summer when IS erased the frontier between Syria and Iraq.

Extraordinary alignments

The 1991 campaign against Iraq created some extraordinary alignments.

Saudi jets hit targets in western Iraq so Israel didn't do it themselves (which would have threatened the entire coalition).

Meanwhile, on the ground, US, UK, French, Syrian, Egyptian, and Gulf state armoured brigades rolled into action side by side.

So now the question is whether Washington's new, disparate coalition can possibly find the same kind of common purpose?

The Turkish border with Syria could be key in the fight against IS

And can it remain true to this mission for years rather than months, as in 1991?

There have been some interesting signs.

Saudi Arabia has committed to step up co-operation with Iraq, and opened an embassy in Baghdad, for the first time since Saddam invaded Kuwait.

Qatar seems to be trying to rein back its support of Muslim Brotherhood militants in some countries, a policy that had brought icy relations with Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

Buffer zones

Sources suggest there are also plans afoot for Saudi, UAE, and Jordanian special forces not just to train "moderate" elements of the Syrian opposition but also to accompany them in battle, for example to co-ordinate air strikes.

After a meeting in Jeddah last month, US Secretary of State John Kerry said that some members of the emerging coalition had offered to conduct air strikes and this is thought to have included Saudi Arabia and the UAE, both of which have impressive air forces.

The ability to interdict foreign fighters as they arrive or leave Syria and Iraq through Turkey will be critical.

Thousands of refugees have been fleeing IS in Syria in recent days

So far, the Turks have been reluctant to make any move, but the recent release of 49 hostages held by IS has set the scene for new options to be discussed when President Recep Tayyip Erdogan meets Mr Obama on Wednesday.

Among the plans reportedly being considered by Turkey are ones that could dramatically change the regional picture.

These include creating military buffer zones inside Syria and Iraq where refugees would be kept (rather than allowing them into Turkey), joining Western air strikes, and a major increase in operations by its internal security service, MIT, to interdict foreign jihadists.

Of these options, the easiest for Turkey to implement would be ramping up the actions of its security service in the border area since it would be barely visible and carry the least potential complications for Turkey's relations with its neighbours.

UK bombing raids?

There are other players too of course, who will involve themselves in more kinetic operations, particularly in Iraq where an invitation from the government for assistance makes action a good deal less problematic legally.

France has now joined the bombing, and many expect the UK to follow suit after President Obama chairs a session of the UN Security Council on Wednesday.

Australia has also committed jets and special forces.

Much of what's being envisaged though and, critically, the drive to create a credible ground force in Syria, and bolster the Kurds and state forces in Iraq, will take many months to achieve.

The defeat of an Iraqi armoured brigade, in the province of Anbar at the weekend, by Sunni militants, shows that these forces still have a long way to travel before there could be attempts to retake Mosul and the other major centres lost to IS in June.

So the re-training of Iraqi forces, in which the US, Australia, and UK are all likely to be involved, will be a long-term business.

It could also easily lead those helping them (for example by bringing in air strikes) into direct combat with the militants.

Admiral James Stavrides, Nato's former supreme allied commander, has told Newsnight, "the odds are overwhelming that they will be involved in combat operations", and that the current 1,600 US troops in Iraq could easily climb to 5,000 or more.

Low-key role?

What all of this suggests is a variety of nations committing to a range of tasks in their own time and at their own political "comfort level".

Like those coalitions marshalled by President George W Bush in Iraq and Afghanistan, many will play a token or very low-key role.

The critical question will be whether countries like Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Turkey are really prepared to use their forces in Syria, and can do so effectively?

And, in Iraq, whether the new government can rally significant Sunni opposition to IS and, using considerable foreign help, re-build its forces to the point where they can recapture the north of the country?