Kobane: Survival stories from Kobane refugees

- Published

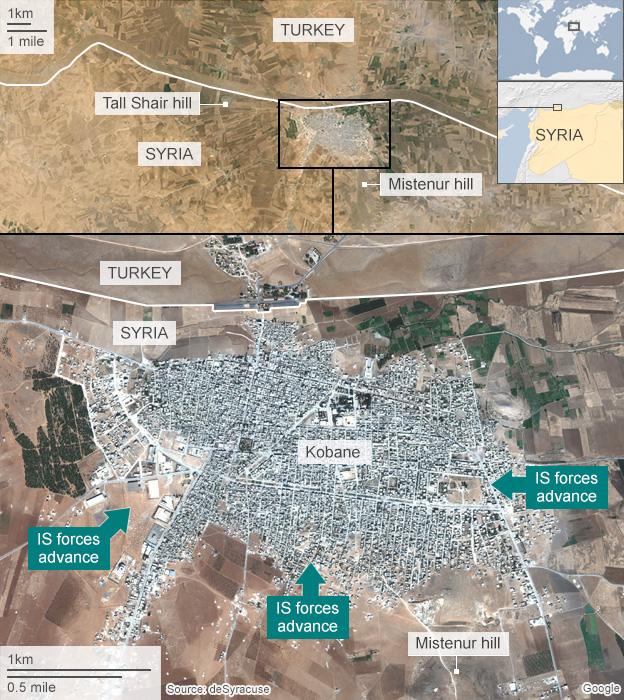

The exodus from the Islamic State onslaught on Kobane has prompted calls for international intervention

Many of the thousands of people who have fled the fighting between Islamic State (IS) militants and fighters from the Syrian Kurdish YPG in Kobane in Syria have reached the relative safety of south-eastern Turkey. In the town of Suruc, the BBC's Rengin Arslan has been listening to their tales of survival.

Vast yellow fields surround this border town. But just across the border inside Syria, white and black plumes of smoke rise above Kobane as Islamic State attacks intensify.

In the past two weeks, thousands of women have managed to escape IS and take refuge in Turkey, only a few kilometres from their own homes.

Their children have been queuing to register for entry into a new country. With rucksacks strapped to their backs, they could be schoolchildren queuing to begin a new term, were it not for the tragic circumstances.

Some 160,000 people are estimated to have fled Kobane in recent weeks

Turkey has had to cope with the biggest single exodus of refugees from Syria as Kurds try to escape from IS

One man carries bright yellow birds in two cages.

It seems everyone's priorities differ when it comes to deciding what to take with them.

Homesick

Hanan, a Kurdish refugee: People "have been sleeping in the streets, in parks and mosques"

On my first day in Suruc, I had hoped to be back home in Istanbul in a matter of days. But the plight of the refugees and the stories I heard kept me at the border. I realised I would be staying longer than I had expected.

I met a man who had lost his leg to a landmine.

He was trying to escape from IS when he stepped on it right on the Syria-Turkey border. Once agricultural land, the Turkish authorities had turned it into a vast minefield in the 1950s to prevent smuggling.

The same day I met a 19-year-old female Syrian Kurd YPG fighter in the main hospital in Urfa.

She told me she had been shot by an IS extremist in a ditch in a village near Kobane. She had shot back. She looked devoid of emotion as she told her story, and I saw her eyes light up only when I asked her to tell me more about her village.

One day at the border, a group of young Kurdish men were tear-gassed by Turkish police as they tried to get home to fight with the YPG.

Most of them made it through.

A Syrian Kurdish woman looks after her child after crossing from Syria into Turkey

Young family members at the Mursitpinar crossing

I then spoke to a woman nearby. Her name was Amira. She had three small children with her. She was sitting on a rock, refusing to move, she said, until it was safe for her to return home. Her youngest boy was crying silently.

That night, I heard there were American air strikes.

Earlier, some of the Kurdish refugees and local residents had told me the air intervention filled them with hope.

Others refused to believe the strikes had actually happened.

"It is all lies. No way were there any US air strikes near Kobane that night," they had told me.

The next day some of the refugees went back across the border to Kobane.

On 6 October IS moved into eastern districts of Kobane and US air strikes continued

Still at the border, I remember one elderly woman in a purple dress, probably in her 70s. She said she longed for home and wanted to die there. She pointed at the small stones on at her feet.

"I sleep on this ground, just like these stones do. But I want to die in the comfort of my own bed."

A few hours later at this same spot, I saw a hearse carrying the coffin of a dead fighter, who had been brought to Turkey for treatment after suffering injuries in the fighting in Kobane. A terrible ending, I thought.

In Suruc, a few days later, Hennan Muhammed told me how IS had taken his son hostage while he was travelling to Iraq to avoid being conscripted by Syria in the war. His son was an English literature graduate, just like me.

Rengin Arslan (r) from BBC Turkish heard moving accounts from those fleeing Kobane

Half way through my trip, a mortar shell landed near the TV satellite trucks stationed on the Turkish side of the border.

Luckily no-one got hurt. But the sound of it was unforgettable, so dangerous and so close.

I filmed a piece-to-camera as safely as I could.

When my recorded video appeared on the BBC Turkish website later that day, I did not post the link on Facebook so my mother would not find out and worry.

Two weeks later, I am back home in Istanbul, hoping to be able to report happier news from the border if I return there.

I hope the distressing sight of grey smoke rising above Kobane will have vanished. And I hope I will never have to wear body armour in my own country again.