No place like home: What to do when jihadists return

- Published

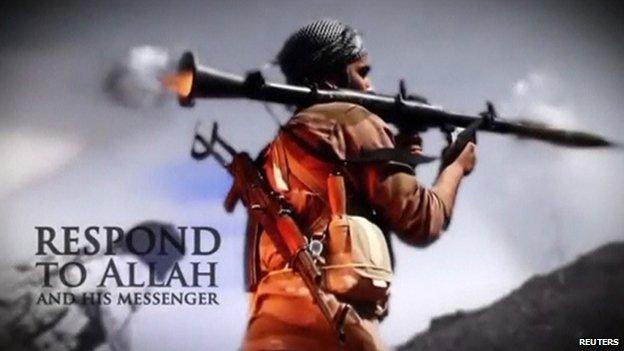

British citizen Abdul Rakib Amin appeared in an Islamic State recruitment video in June

Over 15,000 foreign jihadists from 80 countries are believed to be fighting alongside militants in Syria, the US intelligence agency CIA says. Some countries try to stop the flow, others turn a blind eye, but all face the same problem: what to do when the jihadists return home?

Analysts have drawn parallels between the current conflict and the Afghanistan war of the 1980s. Then, like now, thousands of foreigners flocked there to help the mujahideen (Islamic fighters) battle Soviet forces.

The decade-long conflict finally ended in 1989 with the Islamists victorious. But for many foreign fighters, the war was not over.

One name stands out amongst the jihadists who returned home to countries like Egypt and Algeria to carry out attacks there. Osama Bin Laden, one of the founders of al-Qaeda, was a Saudi Arabian citizen who fought with the mujahideen.

Few wish to see a similar figure emerge from Syria, but there is little consensus on how to prevent this.

Threats and beheadings

Many foreign fighters are believed to have joined militant group Islamic State

In September, Belgium, the country with the highest number of foreign fighters per capita, tried 46 of its citizens - some in absentia - for their involvement with Sharia4Belgium, a group that helped send jihadists to Syria. Only eight appeared at the trial, the others are still in Syria, dead or alive.

Belgium's response is not unusual. France, Australia, Norway and Britain - countries with high numbers of foreign fighters - have also arrested returning jihadists, many of whom joined the militant group Islamic State (IS).

UK police say they have made 218 arrests so far this year while around 40 British citizens are currently awaiting trial on terror charges.

Under existing terror legislation the UK can seize passports of suspected jihadists and detain returnees from Syria for up to 14 days without charge.

The UK government is due to publish a new Counter-Terrorism bill by the end of November which will include special exclusion orders. These measures, which could last for more than two years, will prevent suspected fighters entering the UK unless they agree to strict controls.

Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott, whose government has introduced new anti-terror laws, made his position on foreign fighters clear. "If they come back, they will be taken into detention, because our community will be kept safe by this government," he said.

But deciding who to arrest is difficult. Travelling to Syria is not illegal and determining what foreign fighters did in the country - namely whether they were involved in acts of terror - requires detailed intelligence.

However, the desire to arrest is perhaps understandable. When IS first came to international attention, they claimed the West was not a target. Their goal, they said, was to establish a caliphate in the Middle East, away from Western influences.

Now the situation is different. Western-backed air strikes have angered the group, and they have beheaded British and American captives in what they say is revenge. Videos of the killings come with graphic threats to the West. Bravado perhaps, but a challenge nonetheless.

Careers advice

Still from an IS recruitment video, one of many used to lure foreigners to Syria

In the port city of Aarhus in Denmark, IS threats do not deter the authorities. Instead, returning jihadists are met with counselling and careers advice rather than jail.

The thinking behind the Aarhus model is simple. Many of those who left were young men, some with few prospects, who didn't feel welcome in Danish society. Interrogating and arresting them on their arrival could further radicalise them, but engaging them in dialogue might not.

Officials are also making their presence felt at Aarhus' Grimhojvej mosque. A suspected hotbed for jihadist recruitment - the US claims one of the imams has links to al-Qaeda, which the mosque denies - authorities hope by engaging mosque leaders in debate they can deter future jihadists.

What the experts say

"There is a lot to be said for rehabilitation because it diminishes the problem. It involves exploiting these people to the furthest possible extent ... you get them to cooperate so you get more intelligence." Professor Michael Clarke, director of the Royal United Services Institute

"I think surveillance is the best way. It is a dirty word right now... but surveillance does enable security services to see what people are doing and rank them in terms of what specific threat they might pose." Simon Palombi, consultant for Chatham House

"Even in the event of a conviction, we should be doing whatever we can to reintegrate these [people] into society - or more likely, helping them to integrate - rather than risking their continued radicalisation and the possibility that they may radicalise others." Richard Barrett, senior vice-president at the Soufan Group

"Nobody really knows what works and what does not... I think the main principle in dealing with [foreign fighters] is to tailor the response to each person or to each category of returnee." Thomas Hegghammer, senior research fellow for the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment

Eventually, many fighters might long for the leniency Denmark offers. Hundreds arrive in Syria only to realise the persuasive recruitment videos do not match the brutal reality. But once in Syria, it is difficult to return.

Professor Peter Neumann of King's College London told the Times newspaper in September, external that he had been contacted by 30 British jihadists eager to leave Syria but fearing arrest on their return.

The family of British student Muhammed Mehdi Hassan who was killed in Kobane in October blamed his death on the government making it difficult for foreign fighters to return home.

Jihadists from Saudi Arabia, however, may not worry as much. Despite the country being notoriously harsh on criminals, the kingdom has had its own jihadi rehabilitation programme for several years now.

'Underwear bombing'

Former al-Qaeda militants play volleyball at the Care rehabilitation centre in Riyadh

Set up to help repatriate former Guantanamo Bay inmates, the Care programme offers Islamist extremists counselling and education within an impressive compound in the country's capital Riyadh. Residents discuss the meaning of the Koran with clerics, receive counselling and are helped to find jobs, housing and even wives on their release.

Care claims a 90% success rate but an investigation by the BBC programme Newsnight, external found that two of its residents, once released, escaped to Yemen where they founded al-Qaeda in the Arab Peninsula (AQAP). This group later planned the failed "underwear bombing" attack over Detroit in 2009.

Constant monitoring

If rehabilitation is too "soft", treating returning fighters like criminals can be equally problematic. There is a risk they will turn against their home country or try and travel back to the conflict.

The US has opted for the middle ground. In September, Washington confirmed it was monitoring American jihadists who had returned though no public arrests have been made.

Those that come back from Syria and Iraq do not fit one profile. For every jihadist with extremist views, there are many more who believe their fight is now over.

If used properly, surveillance allows security services to gather evidence against those planning acts of terror, whilst enabling them to reach out to those who don't pose such a threat.

But surveillance, as previous attacks have shown, is not foolproof. Constant monitoring of an individual requires a team of around 30 intelligence officers, and with hundreds of fighters now coming home, security services must make difficult choices about who to watch, and who to leave.