Inside Kobane: Eyewitness account in besieged Kurdish city

- Published

Most of the civilians still in the city are elderly or women with young children

For nearly two months Islamic State (IS) fighters have besieged the Kurdish border city of Kobane in northern Syria. Ersin Caksu is one of the few journalists to have reported from inside Kobane for much of the siege.

I arrived in Kobane on 19 September, four days after the attacks started. Most of the civilians I saw in those early days have now disappeared. Many have fled to Turkey but some, unfortunately, have died in the clashes.

Some 400,000 people used to live in Kobane and in its 360 surrounding villages.

Only 4,000 people now live in the relatively safe areas of the city. There are another 5,000 civilians in Til Seir, a village east of Kobane, in the mined area between the barbed wire of the Turkish border and the railway track.

When the IS attacks started, people took as many of their belongings as they could and moved into this area.

Much of Kobane has been reduced to rubble

There are whole families here, but many have headed to Suruc on the Turkish side of the border.

The only link between Kobane and Suruc is by mobile phone.

People worry about each other on both sides. While the civilians in Kobane are part of the fighting against IS, their loved ones in Suruc are trying to survive as refugees.

Eastern Kobane is in ruins as a result of the fierce fighting, mortar bombs, attempted suicide attacks by IS involving vehicles packed with explosives and also coalition air strikes.

Before the war, this used to be the more affluent part of the city.

The city's southern neighbourhoods, although not as severely damaged as the east, are still devastated.

Street fighting persists in these parts of the city and none of the houses has doors any more.

All are now connected with holes opened on the walls. It is possible to move from house to house through these holes and emerge in a different part of the city four or five streets away.

In every street there are bullet-ridden and overturned vehicles.

Xelil Osman, 67. is fighting to defend Kobane with his two sons

Since the fighting started, the streets have not been cleaned and the city has been invaded by flies. But now the weather is becoming cooler, the stench is less intense.

Hunger and a lack of water has made the situation desperate for Kobane's street dogs and abandoned house pets.

Most of the civilians still here are elderly or women with young children. Although they are not allowed to go to the front line to fight, some defy the ban. Xelil Osman, 67. has taken up arms alongside his two sons.

"When the young are dying, do you expect me to be scared of dying?" he asked me.

At night, civilians only leave their houses in an emergency. If someone falls sick, they call the local authorities and a vehicle arrives with two Popular Protection Unit (YPG) fighters and takes people wherever they need to go.

'Tremendous spirit'

When there is an IS mortar attack or a similar threat, a short term emergency is declared and YPG fighters shepherd people elsewhere and find alternative housing.

At night, civilians do not leave their houses unless there is an emergency

Kobane is imbued with a tremendous spirit of solidarity.

Travelling around the city by day is simple because the first vehicle you meet on the street will stop and the driver will offer you a lift.

Maybe that solidarity helps explain why Kobane has held out for so long.

Very few people are still living in their own houses. When necessary, the doors of empty properties are opened and needy people are relocated.

Those still in their homes share the cheese, pickles, jams and dried vegetables they have stocked for the winter with those in need.

Although people have few belongings left, they get by through sharing what they have.

For example, if a car is needed, the YPG unlock a garage, put the owner's name and the car's number plate on record so that they can be compensated, and the vehicle is used.

Battleground

The main objective of those left in Kobane is to prevent the city from falling

There is a spirit of solidarity among Kobane's defenders

There is no commercial activity in the city. The only business still open is the bakery.

The bread produced here is distributed free among the people.

Other food, which is mainly canned food from the stocks and from the humanitarian aid sent to Kobane, is distributed on certain days of the week as equally as possible.

Water is distributed by tankers. The local administration also distributes flour once every three days. Five households share a 50kg (110lb) sack of flour.

Those civilians who can provide voluntary help behind the frontline.

They repair vehicles, guns and generators, in a city that has had no electricity for the past 18 months.

They help doctors tend to the wounded, carry arms and ammunition to the frontline, cook for fighters and repair their clothes.

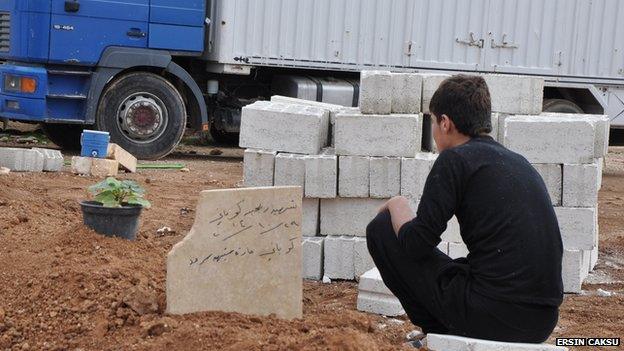

Bodies are buried in a makeshift graveyard as the local cemetery is at the heart of the fighting

As the winter draws in, illnesses here are on the rise and hygiene has become a problem.

There are only five doctors in the city, and because of a severe shortage of resources and equipment, the best they can do is dress the wounds.

Kobane's three hospitals have been damaged by bombing and the doctors work in a small two-roomed building.

Those who become ill refuse to go to the doctors. One elderly woman explained that the medical centre had little equipment anyway.

"It shouldn't be wasted on us. Our kids are fighting and getting wounded. Medical supplies should be used for them."

As the city's cemetery has become a battleground, Kobane's dead are now buried in another area without ceremony.

A woman called Xatun, speaking after the burial of a relative - a young woman fighter - told me there was no time to grieve properly at this point.

"We are not crying now. When Kobane is free, I will cry twice. [Tears] of sadness for the young ones we have buried and [tears] of joy, because their sacrifice was not for nothing and Kobane is free."

Ersin Caksu writes for pro-Kurdish daily Ozgur Gundem.

- Published29 October 2014

- Published16 October 2014

- Published12 August 2014

- Published28 October 2014

- Published20 October 2014

- Published15 October 2019

- Published20 October 2014

- Published27 October 2014

- Published25 June 2015