Syria war refugees' key role in telling the story

- Published

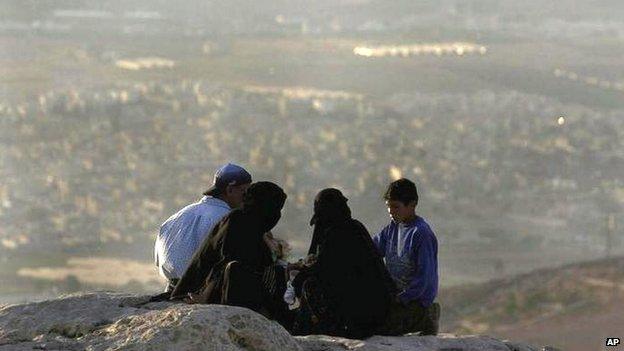

The al-Hassan family are among more than three million Syrian refugees

As Syria's civil war has become more difficult and dangerous to report, it has become a story told increasingly through the experiences of the refugees who left their country to save their lives.

The trouble is that in Jordan those Syrian families are joining previous generations of families who have been fleeing wars across the Middle East for the last 70 years.

So Jordan has welcomed Palestinian, Libyan, Iraqi, Lebanese and Yemeni refugees amongst others, and even has a Somali community in one suburb of the capital, Amman.

Many of them have been in camps for years waiting to go home - notably the Palestinians, who fled the fighting that surrounded the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. Syria was one of the countries in which they sought refuge.

In Jordan, traditionally receptive to desperate migrants, a historian can tell the story of the Middle East through the layers of refugees of different nationalities just as a geologist can tell the story of the earth through the different layers of rock.

Leila Tokhan Al-Houda from the Jordanian Red Crescent Society says simply: " We are the largest refugee hub in the area, if not the world… this is the price you pay when you're a safe country. If we weren't safe and secure, nobody would come."

Chaotic kaleidoscope

Inside Syria the practical difficulties of reporting the war are making it harder and harder to be sure what is happening on the front lines.

Broadly, the forces of Bashar al-Assad and militias drawn from the ethnic and religious communities who support them are fighting a shifting constellation of rival Islamist groups and secular rebels who are also fighting each other.

Iran, Russia, Turkey, the Gulf monarchies and the United States are all trying - with varying degrees of intensity and varying degrees of success - to tilt the battlefield in favour of the groups they support. But it is a chaotic kaleidoscope from which it is hard to extract a clear narrative.

It is no bad thing though that we are forced to tell the story of the war through the voices of the refugees - their broken homes and broken hearts after all are the real measure of the cost of the fighting.

And the Syrian crisis will not really end when guns fall silent - it will end when the refugees feel that it is safe to go home.

As the prospect of Syria emerging the conflict as a single unitary state diminishes and the scale of the destruction continues to grow, most of the refugees are coming to realise that will not be for years - perhaps more than a decade.

'More refugees than citizens'

In the Middle East, refugee crises are coped with and contained - but the underlying problems which created them never seem to be solved.

Nowhere do you see that more clearly than in Jordan, which has a population of about six-and-a-half million and within whose borders there are said to be more refugees than citizens.

The Zaatari facility in Jordan is the world's second-largest refugee camp

The vast bulk of them are Palestinians, who fled in waves triggered by the wars of 1948 and 1967 and have been here ever since.

Some still live in camps, and Amman we found a Syrian family - the al-Hassans from Homs - living alongside Palestinians in the Hussein Camp.

It began as an encampment of canvas tents but has evolved over the years so that these days it looks like any other scruffy, bustling concrete suburb of the city.

It was depressing for the al-Hassans to come here. Imagine all the miseries of the refugee experience - the chaos and terror of fleeing your home and then the humiliations and uncertainties of life in a new country.

And then imagine that you arrive to find you are living alongside refugees who fled fighting nearly 70 years ago and who still cannot go home.

Fear and anxiety

The al-Hassans have settled well - their children are doing well in the refugee schools - but the truth is that they do not find their Palestinian neighbours friendly.

The head of the family - Abu Ismail al-Hassan - understands that is about a deep-seated fear in the older refugee community that their needs might come to seem less important than the needs of newer migrants whose plight is still making headlines around the world.

Sadly the world's generosity - and its attention span for the sufferings of others - are not infinite.

Still Mr al-Hassan does not see why his family should bear the brunt of those anxieties.

"They're really not good to us, to tell you the truth," he said. "I don't know why. After all, the Palestinians have been refugees before in most of the other Arab countries so they should know our situation. They should feel for us. Some of them have treated us badly."

Still, even in the depths of all this uncertainty, Mr al-Hassan, sitting surrounded by his wife, four of his daughters and 10 of his grandchildren, does his best to be positive.

"We don't want to be refugees here," he told us. "We know Jordan is a poor country and we're very grateful. We'd like one day to go back to our own country and for the Palestinians to go back to theirs."

A young Syrian woman I met in a refugee training centre was less hopeful.

She said bluntly: "No issue will be resolved in the Middle East until Syria is resolved - not Palestine and not Iraq. And all the destruction in Syria will have to be fixed - we don't even have homes to go back to any more. It will take years to repair all the damage."

Dream of return

Jordan's record on the refugee issue is impressive and of course it relies on the money and know-how of international agencies like the UNHCR and Unwra to deal with the problems of managing the refugee populations and providing housing, healthcare and education - all this in a country which has few natural resources of its own and hardly enough water for its own people.

Syrians face becoming refugees for generations, like many Palestinians

But while the world's record of coping with the needs of refugees in the Middle East is pretty good, its record at resolving the underlying political circumstances that forced them from their homes is dismal.

Plenty of Lebanese who fled the civil war never went home, and while Iraqis who fled the fighting in 1991 may have returned, you can still meet Iraqis who have arrived arrived in Jordan within the last few weeks, this time fleeing the threat posed by Islamic State militants.

Labib Qumhawi, a Palestinian who fled Nablus during the war of 1967, remains proud of his origins and his identity.

But he knows very well how difficult life as a refugee becomes in the long term.

When I asked what it would mean for the Syrians themselves if they were stuck in Jordan for many years, he said simply: "They'll be raised in Jordan, they'll get education in Jordan, they'll know nothing but Jordan.

"Their fathers and their grandfathers might talk about the good old days in Syria - the fruit, the wealth, the water and the beauty. But all they'll have is the dream that all refugees have - of one day returning to the homeland."

Unless something changes quickly for the Syrian refugees who now find themselves alongside all those previous generation of migrants in Jordan, it is sadly easy to imagine that poignant vision of the future coming true.

You can hear more about Kevin Connolly's Syrian refugee story on The World at One on Radio 4 at 13:00 GMT

Syrian refugees in the region