Islamic State and the idea of statehood

- Published

The US and Arab allies are hitting targets in Syria, but some Western European states refused to take part

Planes, bombs and crack commandos are at the forefront of the battle against Islamic State, but in the background a crucial battle of ideas is tackling one of the biggest questions in international life: what exactly is a state?

Almost every politician, expert and commentator have been clear on one thing: Islamic State is not a state. Islamic State, they say, is a terrorist organisation.

It seems clear enough. IS militants have beheaded people on video. They have ransacked towns and villages. They have killed or threatened to kill anyone who dissents from their view of Islam. They have stolen territory from Iraq and Syria. There is no question of them gaining UN membership, or being accepted by any other international organisation.

Thus, US planes can bomb IS militants without breaking one of the cardinal principles of international law, as outlined in the UN Charter: "All members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state."

There is, however, a problem with the action taken against IS. It is hard to drop bombs on a piece of land without someone accusing you of attacking their "territorial integrity or political independence".

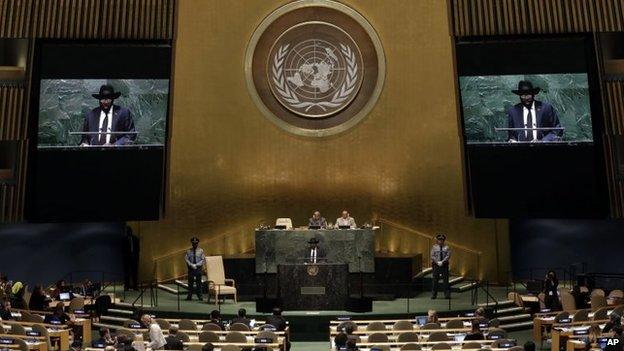

Salva Kiir the trailblazer: The leader of the world's newest state South Sudan speaks at the UN

How to become a state

Get UN membership, external The ultimate goal for aspirant states - they need the support of the Security Council, then two-thirds of the General Assembly

Get recognition If they fail at the UN, aspirant states can get recognition from as many other states as possible and function as a de facto state

Start trading If they have few friends, aspirant states can just start making business deals - political recognition may follow, or it may no longer be needed

In Iraq, the current government formally requested help, external to battle IS. This makes a strong case for bombing IS in Iraq to be both legal and politically defensible.

No such get-out exists in Syria. Bashar al-Assad remains the president of Syria, and Syria remains a sovereign state. Mr Assad has not asked for help, nor has he consented to air strikes.

Despite this, US President Barack Obama recently said, external: "We have communicated to the Syrian regime that when we operate going after Isil [Islamic State] in their air space, that they would be well-advised not to take us on.

"But beyond that, there's no expectation that we are going to in some ways enter an alliance with Assad. He is not credible in that country."

Syria enjoys all the formal trappings of statehood. But the US and its allies do not believe its government has legitimacy. That is enough for its most essential sovereign rights to be overrun, for it to be practically rendered a non-state. Western European states including the UK have not taken part in the bombing of targets in Syria, even though they are part of the anti-IS coalition.

It is possible to say that there are three different concepts of statehood in this story:

Syria: UN member with defined borders, partial control of land, a government disliked by the West, apparently no right to protect its territory

Iraq: UN member with defined borders, partial control of land, a government favoured by the West, able to garner help to protect its territory

Islamic State: Unilaterally declared caliphate, no UN membership, no defined borders, partial control of land, a government with no international recognition, no right to protect its territory

Islamic State's claims have no support among states, but they illustrate that there is no universally accepted definition of statehood. Put the question "What is a state?" to a politician, a lawyer, a sociologist and an economist and you would get four different answers.

Are these states?

Kosovo: Declared independence from Serbia in 2008 after a period of UN administration; recognised, external by more than 100 states; path to UN membership blocked by Russia, external

Palestinian territories: Declared independent by PLO in 1988; currently represented at the UN as a "non-member observer state"; recognised by more than 100 other states but not Security Council members UK, US or France

Abkhazia: Broke away from Georgia in 1999; recognised by Russia and three other states; dependent on Russia for economic support

Somalia, external: Full UN member, wide recognition, but no functioning central government; large areas are governed autonomously

Islamic State uses media campaigns to terrorise opponents and the public

IS has tried to develop the trappings of statehood, flying its own flag and intends to mint a currency

In law, for example, an attempt was made in the 1930s to distil the meaning of statehood in a single treaty - the Montevideo Convention, external. It lists four qualities a state must have:

A permanent population

A defined territory

A government

Capacity to enter into relations with the other states

Crucially, it also attempts to shackle politicians to the law by stipulating: "The political existence of the state is independent of recognition by the other states."

There is little in the Montevideo Convention that would clearly deny statehood to IS, or any other violent group capable of seizing territory and subjugating a population. The Convention has no moral dimension.

But IS, as outlined above, is not regarded as a state. How can it be denied recognition? Not by appealing to any legal rule, but by invoking the moral imperative that violence and terror cannot be rewarded. Politics provides the morality - and subjectivity - that the law lacks.

The UK has taken part in air strikes over Iraq, releasing footage of targets being destroyed

However, the moral dimension is by no means universal.

North Korea, to take just one example, is a state that imprisons many thousands for suspected disloyalty, frequently threatens nuclear war and allows millions to starve through famine. Yet US diplomats rub shoulders with North Korean colleagues in the corridors of power from New York to Geneva. For all practical purposes, North Korea is a state.

Conversely, Taiwan has enjoyed three decades of prosperity under elected governments adhering to international treaties and generally respecting the rights of its citizens. Yet Taiwan is not a UN member and is recognised only by a handful of states. It is euphemistically referred to as "the island". In sporting events it cannot even use the name Taiwan.

For every example, there is an equal and opposite counter-example. Rather than a harmonious international society with defined rules of membership, we seem to exist amid a jumble of entities that fulfil ever-shifting entry standards with varying levels of success.

The military battle against IS is messy, deadly and terrifying for those directly affected. The battle for ideas is genteel by comparison, but it has largely expunged the myth of a universal idea of statehood. The consequences of that are likely to be felt for generations to come.