Israel and the Palestinians: A conflict viewed through olives

- Published

Olive oil from the West Bank has a very special taste

For Israelis and Palestinians everything is politicised, even the olive harvest.

The first time I realised how delicious olive oil from the West Bank can be was more than ten years ago when a Palestinian farmer offered me breakfast as I stood watching a broad strip of his land being destroyed.

He was unlucky enough to live close to Ariel, one of the biggest Jewish settlements Israel has inserted into the land Palestinians want for a state.

In the first few years of this century Israel was in the early stages of building its separation barrier, the complex of walls and high tech fences that it says are necessary to protect its people from attacks by Palestinians.

The barrier would be less controversial if it followed the old 1949 ceasefire line.

It was the boundary between the West Bank, including East Jerusalem and Israel, until the Israeli army captured the area in the 1967 war.

But instead the barrier takes big bites out of land Palestinians consider to be theirs.

That morning it was the turn of the farmer to see the dark earth of his olive groves torn up.

He had tried to move as many trees as possible, but his land was still going to be divided by a fence.

He was going to have to get permits to tend his trees on the other side of the wire. Most farmers, if they are lucky get a day to plough and a day to harvest, assuming the Israeli army is there to let them through gates in the barrier.

Powerful symbol

He invited me back to his house, and served glasses of sweet tea, traditional taboon flatbread, cheese made from the milk of his sheep, and a great bowl of olive oil from his own trees.

I could taste the fruit in the oil, and then a pungent, peppery mouthful. It was impossible to imagine the hills of the West Bank producing anything bland.

Olive oil from the West Bank is perhaps the most political food in the world.

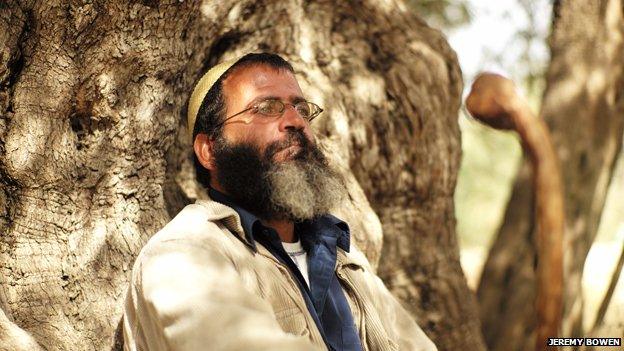

Salah Abu Ali sits in the shade of an olive tree which might be 4,000 years old

The conflict between Israel and the Palestinians has politicised every part of life, from the birth rate to some burials. The annual olive harvest is about much more than oil.

According to the UN office for humanitarian affairs, attacks by Jewish settlers in the last five years on Palestinians and their property have destroyed around 50,000 fruit trees, mainly olives.

Palestinian farmers get a quarter of their incomes from olives, but it's about more than money.

The trees are the most powerful symbol of Palestinian attachment to the land.

A Palestinian farmer called Salah touched one of the branches of the most remarkable olive tree I saw during my trip through the West Bank.

The central core was steel-hard caldera, ancient, gnarled, almost hollow and huge.

I could not get my arms around even a quarter of the main truck, which makes the diameter something approaching 20 feet (more than six metres).

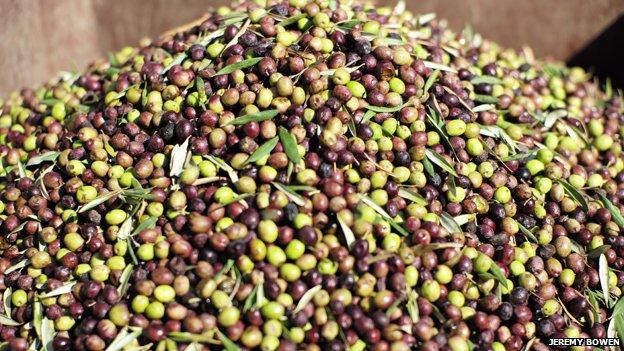

Olives are a staple of Middle Eastern diet

Over centuries new shoots became branches and big trunks in their own right. It is more like a thicket of olives than a single tree, and it would be Salah's prize possession, except he talks about the tree as if it owns him.

"Only God knows how old it is. But it might be around 4,000 years or more. I am honoured to be this tree's servant. The connection goes back to my father and grandfather. I feel so connected to this tree, it's as if it's part of my body and soul," he says.

Salah Abu Ali says: "This is life, like water, honestly I love this tree. I have a relationship with this tree. I know what it needs, what pains it. When I'm around it, I feel safe, I would give it my sweat. This tree stands as a symbol to the Palestinian people, a history, and a civilisation.

"How many generations have passed by it and are now gone, yet the tree is still here today and bearing fruit."

Annual battleground

Mr Abu Ali's land is in Wallejah, a village close to Jerusalem, not far from Bethlehem.

The route of the separation barrier runs very close to the massive, ancient tree.

Mr Abu Ali smiled at me as if I couldn't understand when I told him that the tree, however massive, was just a tree.

For him it was a symbol of his life, the lives of his children and ancestors and their place in the land of Palestine. It was also economically important. The oil was sought-after, and expensive. I found feelings like that everywhere I went.

The harvest is about much more than olives and oil. It is an annual battleground in the struggle for possession and control of land.

The Israeli occupation of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, is enforced by violence and breeds violence. Jewish settlers and Palestinians attack each other.

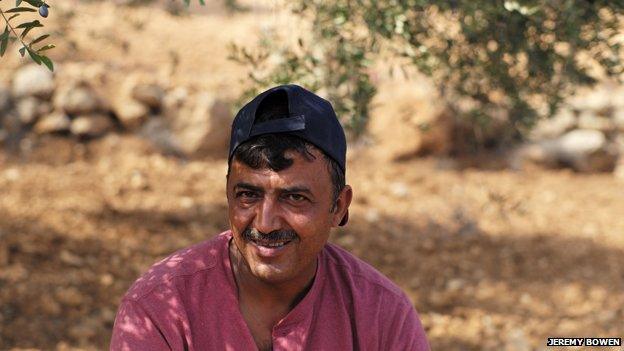

Avraham Herzlich, who was born in Brooklyn, tending his goats

Some Jewish extremists believe the land is theirs alone, and the trees are legitimate targets. Increasingly too, olives have their place in the growing religious war between Muslims and Jews.

In a valley not far below the Jewish settlement of Tapuach, I met Avraham Herzlich.

He is a sharp, charismatic, and a religious Jew who emigrated to Israel from Brooklyn in New York more than 50 years ago.

Mr Herzlich is a guru to the young men in his settlement. His daughter Talia was killed in a Palestinian gun attack in 2000, along with her husband, a rabbi who was the son of the notorious Jewish militant, Meir Kahane.

He herds goats.

Mr Herzlich says they give him a connection to the land he believes God gave to the Jews, a link to the soil and the vegetation that is unobtainable for Israelis living in Tel Aviv and the other towns on the Mediterranean coast, which can seem a long way from the conflict.

He pastures his goats in olive groves that belong to Palestinians from a nearby village. His rangy, wiry animals stand on their long hind legs to pull and chew on the olive branches and the mature fruit.

Under his arm, Mr Herzlich carries the Torah.

The main type of olive in the West Bank is the souri

He has an answer for Palestinians who are angry about the damage his goats do to crops.

"Well, I tell them very simply this is our land. When I see an Arab with a tree I say this is Israel - this is the land of Israel. Are they are your trees? Then take them to your village. This is our land. It's not their land," says Mr Herzlich.

'This is our land'

He brandished his holy book: "Torah tells us this land was given to the people of Israel, to the seat of Abraham, to the seat of and Isaac and Jacob, not to Ishmael. This is our land."

And then Mr Herzlich produced what he said was not a threat, but a statement of fact: "I speak to the Arabs, I tell them I don't want to see them dying.

"They have to leave. Because if they don't leave they're going to die here, they're going to die here. There's going to be another war, and the next war they're not going to be leaving. It's going to be a very difficult war.

"You see there are many who speak about peace with the Arabs but a person that suffered so directly, the Arabs killed my daughter, and made my grandchildren orphans, you cannot measure the pain. The epitome of brutality are these people. They can explode themselves."

Settlers like Mr Herzlich are leaders in their communities, but many mainstream Israelis, including some settlers who moved to the occupied territories for cheap housing and fresh air rather than to be closer to God, consider them at best an expensive nuisance and at worst a threat to the future of Israel and its democracy.

But Mr Herzlich and other ideological settlers are important, because settlers dominate Israeli right wing politics and the debate over the future settlements is one of the key issues that would need to be discussed if ever there was to be another peace process.

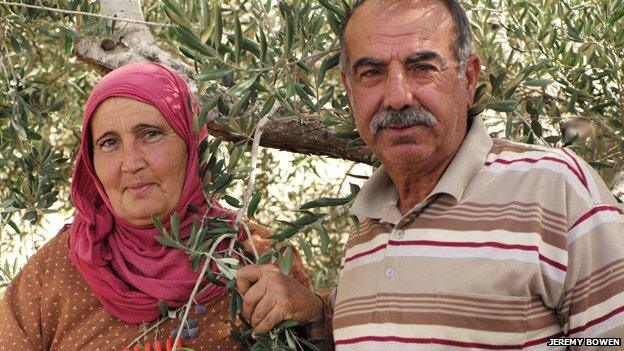

Bassem Rashed and his wife Naja say losing a tree is akin to losing a child

In the valley below Tapuach is a Palestinian village called Yasuf, where Bassem Rashed and his wife Naja were harvesting their olives.

A few days earlier they had heard settlers had used chainsaws to cut down some of their trees, including some that were more than a century old.

Mrs Rashed was close to tears and full of anger: "It feels like bringing up a child, and then losing him. Those trees are our base and roots.

'Everlasting war'

"We felt we were burying a family member. Every week the settlers try to come down to our land. Our men try to stop them and fight them.

"Those settlers say we should be the ones to leave? We prefer to die in our land, let them cut the trees, destroy the land, demolish the homes and attack the children, we will still remain in our land. We won't ever leave, and if they don't, this will continue to be an everlasting war."

The problem is economic as well as emotional.

Mrs Rashed says: "We have a lot less to harvest. We can't get to that land to get the oil and the olives. Almost a third of our harvest is up there, and we've lost all of it.

"We used to take the kids and the old people out with us to the harvest, but we don't anymore. We worry about the settlers coming and attacking us.

"We fear trouble, or getting beaten up, because even if we try to defend ourselves, it becomes our fault, and we're taken to jail or harassed, and we lose our travelling permits."

In a valley not far from Ramallah, where Palestinians living close to a settlement were harvesting olives, two young Israeli officers, Or Maliki and Yam Matir, insisted the army did all it could to stop trouble between Palestinians and settlers.

Israeli soldiers Or Maliki and Yam Matir - trying to keep the peace between settlers and Palestinians

Public order, they said, was the priority and they did not automatically favour Israelis.

The local Palestinian landowner, Abdullah Nassan, welcomed the soldiers and offered them tea from a blackened pot that was sitting on a bonfire of olive trimmings.

Mr Nassan, who owns 7,000 olive trees, did not see things the same way.

He pointed to an olive grove he said the settlers had claimed, which he and his men were not allowed to touch: "When there is a conflict they push us back and they let the settlers do whatever they want.

"But the nice thing about them, when they're here the settlers don't come around. When they're not here they come around, they push us around with guns."

Abdullah Nassan says olives are a poweful symbol to Palestinians

He pointed to a settlement on a neighbouring hill.

"Every time I come here they follow me from that settlement right there. It's very dangerous here to come alone. People are scared because the settlers are very violent and they will come down from that hill and they will harm them," he says.

One day, says Mr Nassan, olives will be a vital part of constructing an independent Palestinian state.

"It's a symbolic issue. This is the only thing that we have left to be honest. What else can we grip on, we have to hold on to the trees. Our goal is to protect our land," he says.

Listen to Jeremy Bowen's report on Olive Wars, broadcast on Radio 4 on Sunday 7 December at 13:30 GMT.