Justice at risk as Pakistan rushes convicts to the gallows

- Published

The BBC's Shaimaa Khalil met the family of one man due to be executed

Pakistan's government has been at pains in the last week to show that it can tackle militancy.

After a daylong meeting with the country's main political parties, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif said military courts would be set up for the speedy trial of suspected terrorists.

Speaking in a television broadcast, Mr Sharif said Pakistan was in an "extraordinary situation" that needed "extraordinary actions".

The Taliban attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar which left 152 people dead, most of them children, shocked the nation and put the political and military leadership in a very tough spot.

A day after the massacre, the military intensified its offensive in North Waziristan. The prime minister lifted a moratorium on the death penalty. Six militants have already been hanged.

Pakistan's interior minister has said 500 people are due to be executed in the next few weeks.

One of them is a man who was convicted as a minor in 2004. Shafqat Hussain was 14 when he was allegedly tortured into confessing to murder, and sentenced to death by an anti-terrorism court.

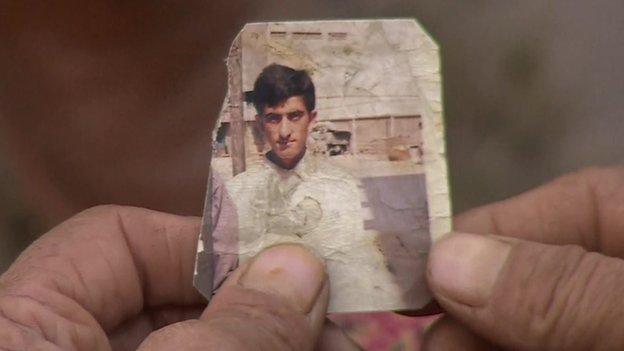

Shafqat Hussain was a minor at the time of his conviction

He was eventually charged with involuntary manslaughter - but remained on death row. Now his family has been told that he could be executed any day.

Shafqat, who is the youngest of seven children, comes from a poor family from Kail sector on the Line of Control with Indian-administered Kashmir.

He left home for Karachi in search of a job more than a decade ago. His parents have not seen him since.

Sobbing, Shafqat's mother said they could not afford to go to Karachi to visit him. His sister, Sumaira, told BBC Urdu's Haroon Rashid that she had borrowed the clothes she was wearing to the interview.

"I can't imagine that my obedient and humble brother can commit a crime. He was so young," she said, tears rolling down her cheeks.

She said the family had only one request: "Please, please let's redo the trial."

Shafqat Hussain's brother and his mother wept throughout the interview

At the scene: The BBC's Haroon Rashid in Muzaffarabad

Shafqat Hussain's elder brother, Manzoor, recalls visiting him in prison in 2011.

"Police took three of his fingernails out. He still has cigarette marks on his body," he says.

"When I asked him about torture in custody, he started shivering and wet his pants. He put both his hands on his head and starting crying, saying, 'Don't ask, I can't tell you what they did'."

"This is how they made him confess a crime he says he never committed."

I met Shafqat's devastated family in Muzaffarabad, the main town of Pakistan-administered Kashmir. The news that hangings were to be resumed after the Peshawar school attack has started giving them sleepless nights again.

Shafqat's 80-year-old mother Makhni Begum, his sister Sumaira, and brother Manzoor, wept throughout the hour that I spent with them.

Makhni Begum said she has not met her youngest son since he left for Karachi in search of a job. "I have almost lost my eyesight because of crying, I have lost my mind because of my son's ordeal," she said. "My life is ruined."

Shafqat's legal team say his case had nothing to do with militancy. They told the BBC they presented evidence to the Sindh High court which showed Shafqat had confessed under duress, and that he was a minor at the time of conviction.

But the appeal was rejected and now his lawyers say they will go to the supreme court.

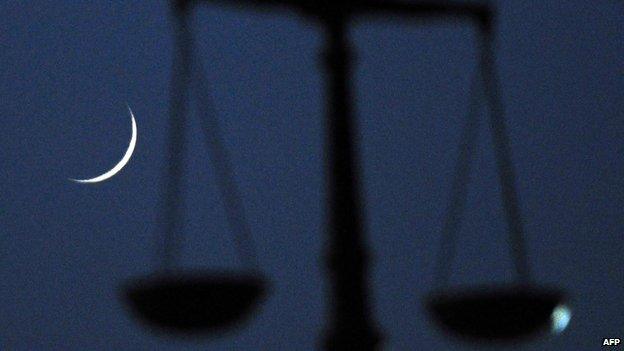

Opponents of the revival of the death penalty say grave injustices could be committed in the rush to punish

Shafqat's lawyer is Sarah Belal, a barrister and director of Justice Project Pakistan, a non-profit human rights law firm.

She said his case was "a perfect example of how the Anti-Terrorism Act and the subsequent terror courts have failed to punish the people they were formed to target".

"Instead, people like Shafqat, too poor and vulnerable to defend themselves, bear the brunt," she added.

'Act of vengeance'

Shafqat's case is not the only one. Lawyers here say that of the 500 people set to be executed in the next few weeks, at least 200 are not terror-related cases.

Both the political and military leadership are under huge pressure to stand up to militants but there are worries that in this wave of executions, the proper legal measures are not being followed.

The government has been accused of a knee-jerk reaction to the Peshawar school attack

Human rights watch have criticised the move, saying it will not combat terrorism and will only perpetuate a cycle of violence.

The EU regretted Pakistan's decision to lift the moratorium and expressed hopes it would be reinstated at the earliest opportunity.

"It's a kneejerk reaction by the government to appease the masses," Shahzad Akbar, a legal fellow at the human rights organisation, Reprieve, said.

"But it doesn't do anything about terrorism," he added. "Instead, those who've been victims of miscarriages of justice are now on execution lists."

"The government is trying to tell people that they are fighting terrorism, but I think this is just an act of vengeance."