The Egyptians paying the price of protest

- Published

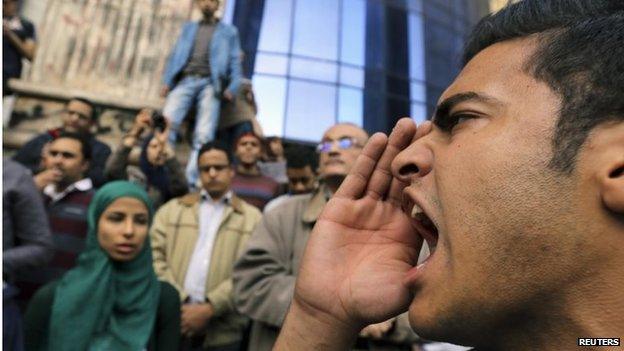

Thousands of people have been detained in a crackdown on anti-government protesters since 2013

"They call him 'Youssef the terrorist'," says Om Youssef, "So when I visit him in the police station, I tell them I'm the mother of the terrorist, what else can I say?"

Youssef is 15 years old. He was arrested late last September on his way to class. Since then he has been held in a police station in his hometown of Fayoum, south of Cairo. The date for his trial has not yet been set.

Om Youssef did not know where her son was for four days after his arrest. While he was under investigation he says he was beaten and electrocuted.

Youssef is accused of causing an explosion at a kiosk in the city. He admitted the charges after those four days with the police.

Gen Abu Bakr Abdel Karim, an aide to the Interior Minister, denies that beating and electrocution take place in Egyptian police stations.

"If that were ever to happen," he says, "police officers would be held accountable."

Protests 'only way'

Youssef's lawyer, Yasmine Hosam El-Din, was finally able to see him on the fifth day after his arrest, and a photograph she took shows his face covered in scratches. She says there is no evidence against him.

Youssef's father was killed when an anti-government sit-in in Cairo was violently dispersed in 2013. His mother believes that is why her son was arrested - because the police are afraid he will take revenge for his father's death.

Lawyer Yasmine Hosam El-Din is critical of the anti-protest law

Om Youssef says her family are not members of the now outlawed Muslim Brotherhood. But when I ask her if she marches at their weekly protests, she pauses. "Actually," she says, "I do, I'm not going to lie. Because I have a fire inside. I feel people like my family have no right to life and protesting is the only way the authorities will take notice."

But protesting in Egypt has become increasingly dangerous. A law brought in at the end of 2013 requires agreement from the Interior Ministry for any protest.

Activists say this is effectively a ban on protesting. Hundreds of people have been arrested under this law and are facing trial or jail time.

Gen Abdel Karim says, though, that the law "was written in order to control the security situation and address the violence by non-peaceful protesters".

"It doesn't ban [protesting], it gives the right [to do it]. But it gives the right in the framework of keeping the peace."

Inefficient system

Yasmine Hosam El-Din is part of the defence team on two cases in Cairo involving demonstrations against the protest law.

"The accusation is that they haven't asked for permission," she says. "But it doesn't make sense for me to ask permission to protest against [the anti-protest] law."

One of the defendants is Yara Sallam, a human rights lawyer and researcher working for the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights.

According to her mother, Rawia Sadek, and her lawyer, she was arrested buying water from a kiosk near the protest.

Human rights lawyer Yara Sallam (back, left) was put on trial with 22 other defendants

Amid a tightening of restrictions on non-governmental organisations, her mother believes she was detained because of her work on human rights.

"In that moment, when they took her by force," says Rawia of her arrest, "I always remember it and think she was alone. That's the moment that really upsets me."

Yara and her 22 co-defendants were sentenced to three years in jail followed by three years' probation. That sentence was reduced to two years after an appeal. The lawyers are now filing another appeal.

Egypt's justice system is notoriously slow and bureaucratic. This has caused problems for many years, according to Ms El-Din.

Almost nothing is computerised and many logistical decisions are left to individual judges.

Sometimes journalists are allowed in court and sometimes cameras and phones are permitted, but sometimes not.

Often family members are banned from entering, but Rawia Sadeq had a press pass on the day of her daughter, Yara's, verdict.

"The [defendants'] cage was made of thick iron grille so you couldn't see them easily. Then I saw her. She was upset and I didn't know what to do. I wanted to hug her, soothe her. She said: 'Mum don't cry, don't be upset.'

"Some of her fingers came out of the iron grating, so I kissed them. I didn't know what to do."

'Turning on judiciary'

After the 2011 uprising that toppled President Hosni Mubarak, political activists believed they had won freedoms and that those freedoms had now been taken away.

Laila Soueif, whose younger daughter Sanaa Seif is Yara Sallam's fellow defendant, believes the next wave of uprisings will be against the judiciary.

"People know the police are oppressive," she says, "but the oppression that is new comes from the judges."

Gen Abdel Karim is keen to stress that the judicial system functions correctly. "The court gives its verdict based on evidence and documents," he says.

"When a defendant is referred to trial it means that the investigations show that this person committed a crime… And lots of people have been released [after their arrest or trial]."

Youssef's lawyer believes there is still hope for change.

"All I'm dreaming about now is getting the detainees out," says Ms El-Din. My dream is non-politicised judges. All of these things can be achieved if we are insistent enough.

"Even if they're achieved on the last day of my life, I will keep on."

Facing a year-and-a-half more in jail with her fellow defendants, Yara Sallam too remains positive, her mother says.

"She put in one of her letters: 'I don't feel that I'm jailed. A person's feelings come from inside. He could be walking in the street but feel like a prisoner; and he could be jailed and feel that he's free because he's convinced he's defending something right.

"'He doesn't just take freedom for any price.'"