Yemen on brink as Gulf Co-operation Council initiative fails

- Published

As the US, other Nato powers and neighbouring monarchies - the "Group of 10" - shut down their embassies in Sanaa and evacuated their diplomats earlier this month, the UN Security Council unanimously approved Resolution 2201, external.

It called on Houthi rebels to surrender their military gains and everyone to get behind the 2011 Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) initiative and the recently completed draft constitution.

Jamal Benomar, the UN special envoy to Yemen, is worried that instead of successfully implementing the GCC initiative, the country might be heading towards civil war. His concerns are valid.

But a multi-polar balance of military power and indigenous political mediation might yet forestall widespread violence.

Peaceful uprising

Here is a brief synopsis of the GCC initiative.

In 2011, there was a mass uprising/camp-out across Yemen. It was mostly peaceful, although more than 50 demonstrators were killed in March, and President Ali Abdullah Saleh himself was seriously injured in an assassination attempt in June.

Demonstrations calling for the end of Ali Abdullah Saleh's 33-year rule began in January 2011

While Mr Saleh was recuperating in Saudi Arabia, leaders of a National Dialogue that had tried to negotiate the impasse between Northern and Southern leaders before the outbreak of a civil war in 1994 re-launched that Dialogue.

This project was overtaken by the GCC deal with Mr Saleh, whereby he handed presidential power to his hand-picked Vice-President, Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, in exchange for immunity.

Mr Saleh also remained the head of the ruling General People's Congress (GPC) party, which in turn retained its parliamentary majority.

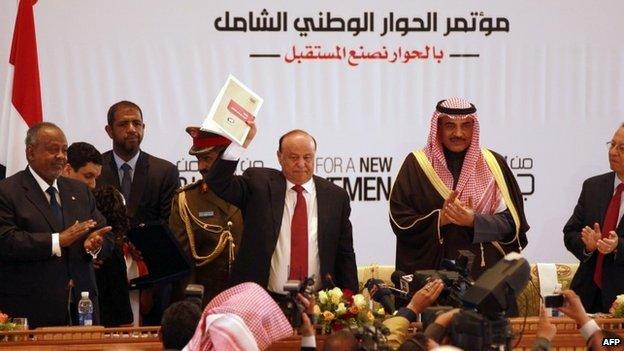

The UN's Jamal Benomar helped pave the way for the GCC initiative that saw Mr Saleh step down in 2012

This deal was signed in Saudi Arabia, with witnesses from the Gulf monarchies but not Yemen's "revolutionary youth".

Activists sidelined

A National Dialogue Conference (NDC) was also convened as part of the deal.

It was a very good idea, grounded in Yemeni precedents, and helped tamp down tensions in 2012 and part of 2013. But in the end it did not deliver.

Although the NDC involved young and/or female intellectuals and technocrats, most delegates were aging politicians.

The National Dialogue Conference document was hailed as the beginning of the road to a new Yemen

Working groups tackled a range of issues - from economic development to the Houthi and Southern problems, respectively, although those dissident groups were under-represented in the negotiations. Some working groups made real progress.

However, the NDC became a donor-dominated transitology project, envisioned by foreign experts and GCC backers rather than Yemeni activists.

Some 560 delegates earned generous per diems to meet in the five-star Moevenpick Hotel in suburban Sanaa, where international consultants' lectures were simultaneously translated into Arabic before everyone enjoyed excellent buffet lunches.

The rent-driven conference persisted, irresolutely, well beyond its initial timeline.

Political order rewritten

Ironically, a major outcome - the federalism proposal dividing the country into six administrative regions, as recommended by the World Bank - was not on the agenda, mission statement or committee structure of the NDC.

The Houthi rebel movement backed the NDC but rejected the draft constitution

It seemed to be based on the utterly failed federal constitution of Iraq rather than on any on-the-ground demands for local autonomy in Yemen.

Accordingly, the draft constitution, external endorsed by the UN proposed a radical rewriting of a political order heretofore based on 21 governorates.

The newly proposed governance model neither addressed the demands of the revolutionary youth nor provided for the decentralised federalism most Yemenis want.

The Gulf Co-operation Council has denounced the Houthi takeover of Yemen as a "coup"

For instance, or especially, it remade the House of Representatives, the lower house of parliament, to consist of 260 members elected through a nationwide vote under a closed proportional list system - instead of the 301 district constituency seats in the previous House.

Other provisions for electing a new upper house or even the next president and vice-president lack either popular support or genuinely federal logic.

Power struggle

Mr Benomar, the GCC, the UN and G-10 hoped to placate Yemenis' aspirations for social justice via managed negotiations among factions of the ancien regime and anti-democratic Gulf monarchies.

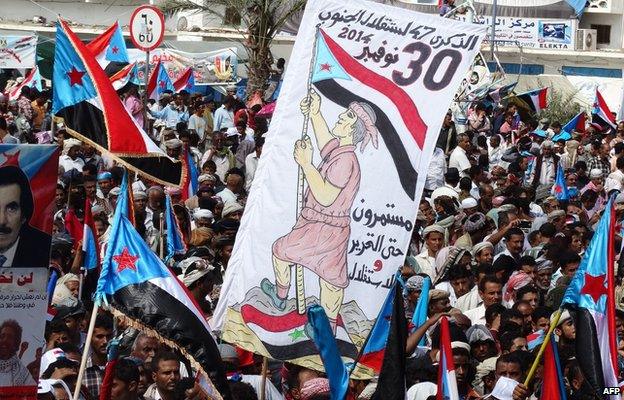

But anti-systemic movements - the ragtag Houthi militia astonished by the lack of resistance to their advance against the flailing "transitional" regime; the separatist Southern Movement (Hiraak al-Janoubi), also marginalised from the National Dialogue but now taking up arms; fringe Yemeni and foreign Salafist fighters for al-Qaeda; and divisions of what used to be Mr Saleh's security apparatus - are jockeying for power in the new order.

Some are demanding greater autonomy or even independence for South Yemen

Mr Benomar rightfully frets that the collapse of UN-sponsored talks between the Houthis and the main political factions might embolden multiple well-armed forces to resort to military struggle.

The GCC initiative to ward off revolutionary democratisation in the Arabian Peninsula via a managed dialogue has already aborted.

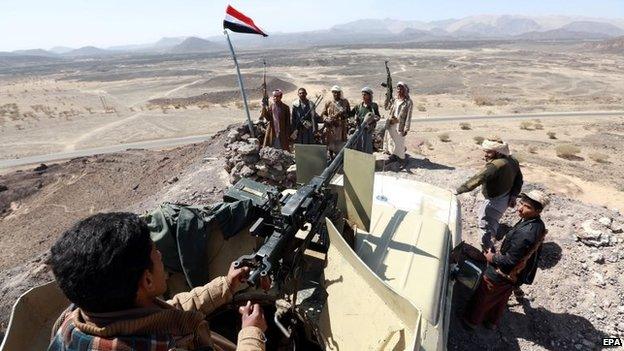

Clashes between and among rival factions are reported in various locations, including Sanaa and the oil-rich desert governorate of Marib. However these are localised gun battles over particular installations, whether government buildings or oil facilities.

Hiraak, certainly, Marib tribes, and even the Houthis are fighting for self-governance and seats at the negotiating table rather than control of the central government.

Sunni tribesmen are in control of Marib province, where Yemen's oil infrastructure is based

The national army, split since March 2011, has not seriously resisted Houthi advances.

The erstwhile President Hadi resigned and moved to Aden rather than battling for control of Sanaa.

Brinksmanship might get out of hand, of course, but no one faction can hope to rule the country by force alone, and all remain wary of mayhem.

Warfare is diplomacy by other means. There is still a glimmer of hope for genuine multiparty National Dialogue.

Dr Sheila Carapico is professor of political science and international studies at the University of Richmond, Virginia