Netanyahu's speech 'win-win' for Iran

- Published

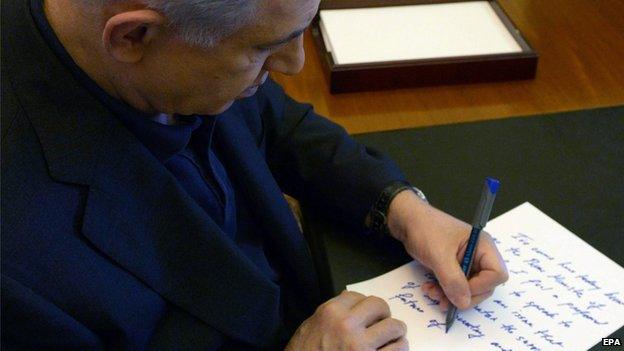

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu working on his speech to the US Congress in his Jerusalem offices

Nobody will be observing the media frenzy surrounding the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's speech to the US Congress on Tuesday with more interest, and with perhaps a certain amount of amusement, than the Iranians.

The tensions between US and Israeli leaders will be welcome. Nothing Mr Netanyahu can say will derail a nuclear deal if one is really possible.

And if there is no deal, why then Mr Netanyahu may well have to share some of the blame rather than just Tehran. In the short term, it is a win-win for Iran.

This though is a strategic moment for the Iranians and they would do well to disregard the "noises off" from the ebullient Mr Netanyahu. The obituaries for the Israel-US relationship may also be premature.

'Key player'

For many years, Iran has been seen in the West as the prime author of instability in the region, given its support for Hamas, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and its meddling in a variety of other conflicts.

No matter that it was US policy in destroying Saddam Hussein's Iraq that vaulted Tehran into this position of regional ambition. Iran had suddenly become a player to be reckoned with.

And now even more so given the chaos in Syria, Iraq and Yemen.

But the rise of Islamic State has changed Tehran's calculations. Its support for Syria's embattled President Bashar al-Assad and for the shaky government in Iraq now has an even more avowedly strategic dimension.

And these same strategic concerns are playing into the debate over its nuclear programme as well.

To be clear, a nuclear deal between Iran and the West is still no certainty.

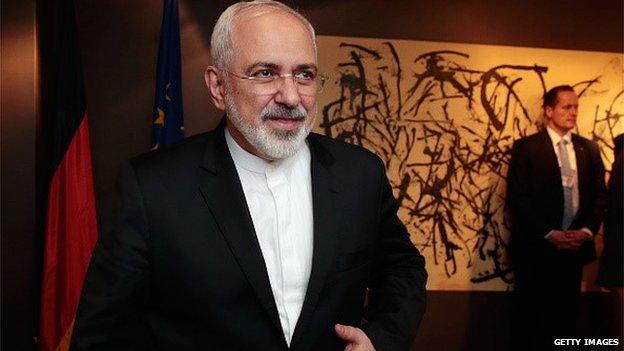

Mr Netanyahu's angst may be premature. But important progress has been made, not least at a meeting between US Secretary of State John Kerry and the Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif in the margins of the Munich security conference last month.

Iran's Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif held two bilateral meetings with US Secretary of State John Kerry at the Munich security conference

Of course at the outset the initial aim of the talks was to simply roll back Iran's nuclear programme.

Some hoped that it would be forced to abandon uranium enrichment altogether. That though was a forlorn hope. Iran has stuck to its proclaimed right to enrich under the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and shows no sign of budging.

What is the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)?

The NPT was created to prevent new nuclear states emerging, to promote co-operation in the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to work towards nuclear disarmament

When it came into force in 1970, there were five declared nuclear states - the US, the Soviet Union (now Russia), China, Britain and France. These states are bound not to transfer nuclear weapons or to help non-nuclear states to obtain them

On 11 May 1995, the treaty was extended indefinitely

A total of 190 states have joined the treaty, though North Korea, which acceded to the NPT in 1985 but never came into compliance, announced its withdrawal in 2003

Four UN member states have never joined the NPT: India, Israel, Pakistan and South Sudan

The treaty allows for parties to develop, research, produce and use nuclear energy for peaceful purposes without discrimination providing they renounce any desire to have nuclear weapons and allow the appropriate inspections and safeguards by the International Atomic Energy Agency

As the talks have gone on, the fundamental issue (and there were many so this is a simplification) was how to constrain Iran's programme in such a way that any attempt to break out from the NPT's constraints and dash for a bomb would not just be visible, but would be seen in sufficient time for the international community to do something about it.

It is extending this "breakout" time that has been the crux of much of the debate. The deadline for these talks to bear fruit - 24 March - is fast approaching.

Progress has reportedly been made in a number of areas. A balance needs to be struck between enrichment activity; the stocks of enriched material retained and the level of verification required to ensure that any deal sticks.

Benjamin Netanyahu's speech to Congress was arranged by senior Republican opponents of Barack Obama and the Israeli Ambassador to Washington, in effect behind the president's back.

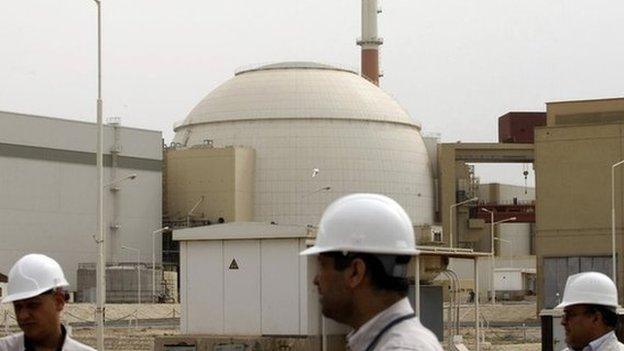

Iran now seems willing to accept a package of measures including a reduction in the number of centrifuges spinning and changes to their configuration.

It also is reportedly willing to export most of its enriched uranium stocks to Russia. It will also countenance changes to the design of the Arak reactor to reduce the level of plutonium it might produce.

There has also been some progress on the duration of any deal - perhaps some 10 to 15 years - and the sequencing of how restrictions on Tehran might be lifted. Some restrictions would remain in place for longer.

Any deal will have to be bolstered by a rigorous effort to ensure it is adhered to. Having sufficient warning time of any breakout is one thing. Deciding in advance what you would do in such a circumstance is quite another.

That is something Mr Netanyahu could usefully talk to the Americans about. Sadly he will not be speaking to any senior officials on this trip!

Are you in Israel? What are your hopes and expectations for Mr Netanyahu's speech? You can share your thoughts by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published2 March 2015

- Published26 February 2015

- Published26 February 2015

- Published19 February 2015

- Published25 November 2014