Unrivalled riches of Nimrud, capital of world's 'first' empire

- Published

Nimrud has yielded riches of a technical skill and aesthetic sense unrivalled in the ancient world

Ancient Iraq is famous for many global "firsts" - Mesopotamia gave us the first writing, the first city, the first written law code, and arguably the first empire.

The people of Iraq are justifiably proud of this ancient heritage and its innovations and impact on the world.

The reported destruction by Islamic State militants at Nimrud, following similar destruction at the site of Nineveh and the Mosul Museum, is an attack on the people of Iraq as well as a tragedy for the world's cultural heritage.

Nimrud was the capital of what many scholars consider the world's first empire, the Neo-Assyrian Empire of the 1st millennium BC.

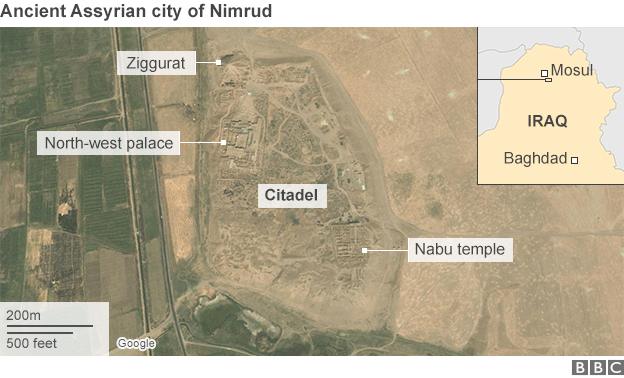

Lying 35km (22 miles) south of the modern city of Mosul in north Iraq, Nimrud covers some 3.5 sq km (1.35 sq miles), with a prominent "citadel" mound within the city walls, on which are clustered the main administrative and religious buildings.

These buildings include the enormous palaces of several Assyrian kings and the temples of Ninurta, the god of war, and of Nabu, the god of writing.

The site was first established by the 6th millennium BC but was expanded and developed into the ancient imperial city of Kalhu by King Ashurnasirpal II from about 880 BC.

It remained the Assyrian imperial capital until about 700 BC and continued to be an important city until 612 BC and the collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Hunting lions

The Palace of Ashurnasirpal, also known as the North-West Palace, was first excavated by the British explorer Austen Henry Layard in the 1840s. His excavations are the source of the winged bull gatekeeper statues currently displayed in the British Museum.

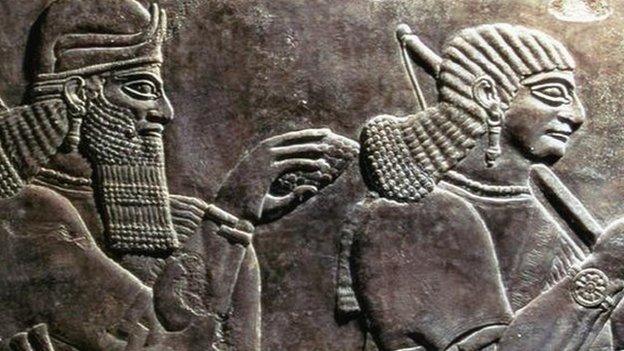

Layard also recovered large numbers of stone panels that lined the walls of rooms and courtyards within the palace. These panels are of a local limestone, carved in low relief with beautifully detailed scenes of the king seated at state banquets, hunting lions, or engaged in warfare and religious ritual.

Extended excavations at Nimrud were next carried out in the 1950s-60s by Max Mallowan, the husband of crime writer Agatha Christie.

Mallowan and his team reconstructed the complex plans of the palace, temples and citadel, and his excavations recovered rich finds of carved ivory furniture, stone jars and metalwork, as well as hundreds of additional wall reliefs and wall paintings.

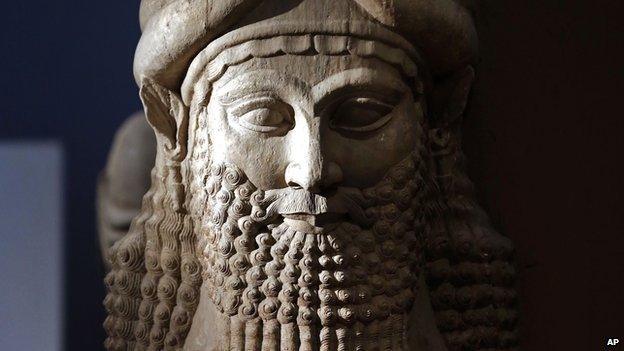

The winged bulls combine highly prized attributes from the animal world with human parts

Here, a protective spirit from Nimrud is displayed in Abu Dhabi in 2001

Near the entrance to the palace's throne room, Mallowan also discovered a free-standing stone slab, which depicted the king in a pose of worship and included a long text in Assyrian cuneiform that described the construction of the palace and its surrounding gardens.

Banquet for 70,000

The text's details of precious metal door fittings, cedar roof beams, and hundreds of artisans at work hint at the unique reach and power of the Assyrian empire.

This text also described a luxurious banquet for almost 70,000 guests that took place at the palace's dedication, involving hundreds of animals and birds, fruit, and flowing beer and wine.

Other rooms of the palaces and temples contained archives of the imperial administration.

Large parts of Ashurnasirpal's palace were reconstructed by Iraq's antiquities board during the 1970s and 1980s, including the restoration and re-installation of carved stone reliefs lining the walls of many rooms.

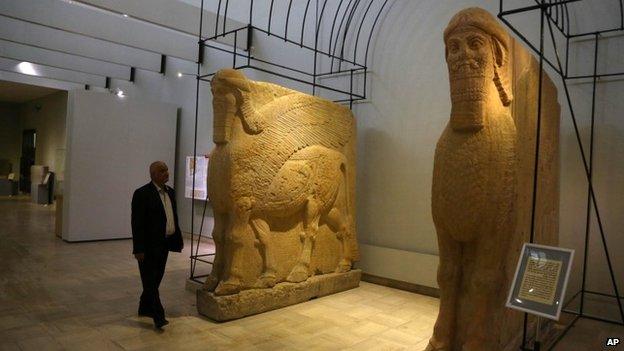

The winged bull statues that guard the entrances to the most important rooms and courtyards were re-erected.

These winged bulls are among the most dramatic and easily recognised symbols of the Assyrian world.

They combine the most highly valued attributes of figures from nature into a complex hybrid form: a human head for wisdom, the body of a wild bull for physical power, and the wings of an eagle for the ability to soar high and far and to see and prevent evil.

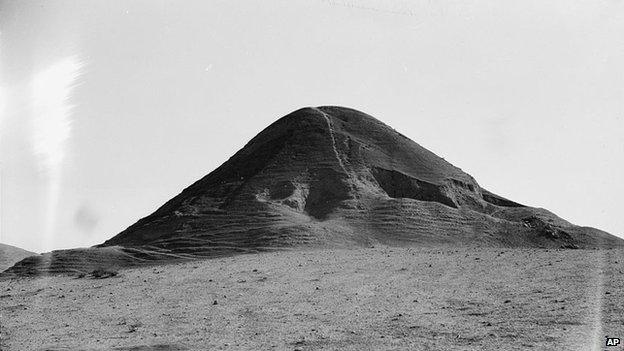

A view of a hill at Nimrud in 1932, before many of the most spectacular finds had been made

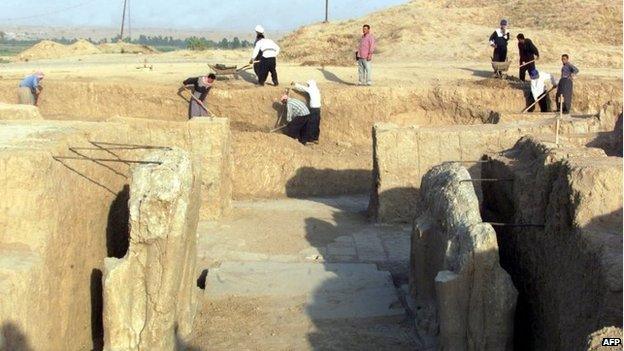

Many have been removed, but the artefacts left behind - here being cleaned in 2001 - are feared destroyed

The Iraqi restoration project also led to the dramatic discovery of several tombs of the queens of the Assyrian empire. These tombs contained astonishingly rich finds of delicate gold jewellery and crowns, enamel ornaments, bronze and gold bowls, and ivory vessels.

The technical skill and aesthetic sense of the artisans responsible are unrivalled in the ancient world.

Nimrud was for a long time a popular site for family picnics and local school group visits, and the reconstruction of the palace provided a rare opportunity for visitors to experience the buildings' scale and beauty in a way that is impossible to find in a museum context.

Nimrud is unique and its buildings and artworks are irreplaceable.

This destruction is a huge loss for archaeologists, for Iraqis, and for the world.

- Published6 March 2015

- Published6 March 2015

- Published21 May 2015

- Published17 February 2015