Yemen campaign key test for Saudi Arabia

- Published

A Saudi-led coalition launched air strikes after rebels closed in on President Hadi's stronghold

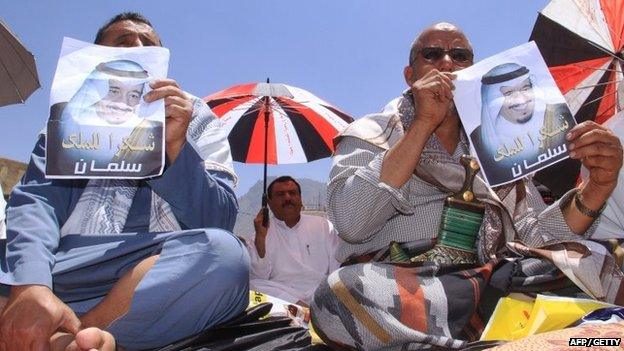

The decision by King Salman bin Abdulaziz al-Saud to order airstrikes against Houthi rebels is the most important foreign policy decision undertaken by the House of Saud since revolutions swept across the Arab world four years ago.

Saudi media claim the kingdom has mobilised as many as 150,000 troops to its southern border primarily for the purpose of homeland defence, but also clearly to afford the kingdom the option to stage a ground war should it so choose. It is not possible to verify the troop numbers, which may not accurately reflect the actual size of the deployment.

Whether such a ground intervention will come is as yet unclear, but the kingdom has decisively played its hand against the Houthis, and in the process dramatically upped the stakes in a regional power struggle with Iran which now involves Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Bahrain and Yemen.

Saudi Arabia's major foreign policy decisions are usually the product of consensus among top princes, and the Yemen operation is no exception.

Indeed, had the previous King Abdullah still been alive he would almost certainly have come to the same conclusion.

Ordering airstrikes was a momentous foreign policy decision for King Salman

Nevertheless, this is a real test for the new king, and failure to achieve Saudi Arabia's aim of reinstating ousted President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi would be an embarrassing defeat.

Failure is not an option, in particular for the king's 34-year-old son Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who as minister of defence is serving in his first senior post in government.

The risks for the young man are great.

His cousin Prince Khalid bin Sultan bin Abdul Aziz al-Saud launched what is widely regarded as a failed operation in Yemen in 2009, and his career has never fully recovered, with the one-time shoo-in for minister of defence seeing his portfolio dim dramatically.

Although Prince Mohammed is secure in his post, the problems would begin if his aging father were to pass away - the Byzantine world of Saudi court politics would be unlikely to forgive a failed Yemeni operation.

Prince Mohammed (right) received Mr Hadi in Saudi Arabia after the president fled Yemen

The young prince must ensure that he gets this right. The stakes are high.

It is unlikely that the kingdom is looking to involve itself in a protracted conflict.

Saudi troops marching into Yemen have found it tough going since 1934. Logistics and supply lines are hard to maintain, and Yemenis know their rugged terrain better than any foreigner.

Leverage

An extended occupation of the country would be disastrously costly both financially and in terms of lives, even if the Houthi insurgency was militarily defeated.

The question is what does Saudi Arabia seek to achieve through the use of military force.

Air strikes alone will not be enough to defeat the Houthis, and a long term military operation would stretch Saudi operating capacity thin.

Air strikes have targeted arms depots and the Houthi movement's leaders

The message from Riyadh also leaves no doubt that the Saudis seek a negotiated settlement in which President Hadi brings together Yemen's different constituencies, including the Houthis, to work out a fairer constitutional settlement.

This could include a fairer distribution of provinces, and possibly more autonomy for Yemen's south where agitation from separatists is growing larger by the day.

Additionally, it is important to understand whether Saudi Arabia seeks a solution in Yemen with the hope of affecting affairs elsewhere in the Arab world.

Could for example, a political deal in which the Houthis are on the backfoot in Sanaa be used as leverage against the Iranians in Syria to force President Bashar al-Assad to step down from power or allow greater Sunni political influence in Baghdad?

Iranian support

It is a long shot but given current regional dynamics the Saudis will be looking to push all of the pressure points they can get against Iran and its allies.

Iran's position on Yemen is also quite clear - it seeks a political solution in Yemen that does not involve long term conflict and in which its allies, the Houthis, are given a seat at the table.

But should this not be possible the hardliners in Tehran would like nothing more than to see the Saudis bogged down in a conflict that they cannot hope to win.

Although Iran's logistical and diplomatic support to the Houthis has been fairly limited, the level of the military response in Riyadh shows that the Iranians clearly have the Saudis rattled, for far less time and money than the Saudis expended in Syria to force Iran's hand.

Houthis have vowed to fight on in the face of the Saudi-led campaign

In a conflict in which no side has indicated that it seeks anything other than a diplomatic solution, it seems odd that the risk for protracted conflict is so high.

However, the Houthis do not look to be backing down.

Houthi leader Abdul Malik al-Houthi indicated in a televised address shortly after the airstrikes began that all foreign invaders would be resisted.

Danger

The hope is that while the Houthis talk tough, that they understand that they are not welcomed by the local population and by tribal confederations across large swathes of Yemen, particularly in the north east and south west of the country.

So whether the Houthis like it or not, they will have to compromise.

The danger is that Yemen could descend into a fractured and long term war, which drags in the region's main players and gives additional space for al-Qaeda and Islamic State (IS) to exploit.

To avoid such a scenario, much depends on the ability of all parties to come out of this conflict without appearing to have lost face.

Because, if the Syria example is anything to go by, a war will continue indefinitely until all parties feel they have more to gain from talking and compromising than they do from fighting.

Michael Stephens is Research Fellow for Middle East studies and Head of RUSI Qatar (Twitter: @MStephensGulf)