Iran nuclear deal has hungry investors circling

- Published

Iranian businesses have been stymied for years by a raft of international sanctions

A preliminary deal between Iran and world powers, which will see international sanctions lifted in return for Iranian curbs on its nuclear programme, has boosted the appetite for doing business in Iran at the earliest opportunity.

The first time he answered his phone, Xanyar Kamangar was in the passport queue at Tehran airport, the day after Iran and world powers agreed on the framework for a nuclear deal.

The second time was a couple of days later, well past midnight Tehran time, while Mr Kamangar was working on closing a deal of his own. He barely had time for a telephone interview.

The 39-year old Iranian-born banker left his well-paid job at Deutsche Bank in London late last year to co-found Griffon Capital, a corporate finance advisory and asset management firm "betting on Iran opening up."

"It's a generational opportunity and a chance to make a difference," said Mr Kamangar, a graduate of the London Business School.

"If you think Russia was big, Iran is going to be even bigger, because Iran has the [financial] framework and regulations, but Russia was the Wild West when it opened up!"

Mr Kamangar's firm has already valued, raised and closed significant investment from mostly European firms for DigiKala, a fast-growing online retail operation, valuing it close to $150m (£100m).

Although modest by global comparison, this is the largest investment yet in a technology start-up in Iran. European investors had to apply for exemptions from sanctions from their respective governments.

Starting gun

Sanctions by the United States and the European Union on Iran's financial, energy and trade sectors have held back the country once described as "the biggest untapped market before Mars and the Moon" by Martin Sorrel of advertising giant WPP.

Some anticipate a "gold rush" once Iran's 77-million-strong, highly educated, consumption-savvy market opens up.

Marathon talks in Lausanne capped 12 years of negotiations

When asked how quickly economic sanctions could be removed, US Secretary of State John Kerry told reporters it depended on how fast Iran could deliver its side of the bargain by limiting its nuclear activities.

Mr Kerry estimated the amount of work Iran had to do was "in the vicinity of four months to a year" from the date of the final deal, now aimed at 30 June.

Since the Geneva interim nuclear deal with Iran in November 2013, many European and even American conglomerates have already drawn up plans to enter the market.

They have found partners and agents and negotiated contracts. Some have even provisionally recruited staff, while others have been looking at properties to live or work in - all waiting for the "starting gun".

More than Iranian expats, a nuclear deal and sanctions relief could benefit those living inside the country: from cancer patients who struggled to find their prized imported medicine, to the country's aviation industry crippled by lack of spare parts.

But most of all, Iran's middle class is geared up for a resurgence.

Risk factor

Not all is that rosy when it comes to doing business in Iran. The economy is predominantly run by powerful entities close to the country's Supreme Leader, the security forces and the military, some of whom are hardly accountable to anyone, let alone the judiciary.

In 2004, the powerful Revolutionary Guards kicked out a Turkish airport services company from a contract for Tehran's then-new airport, citing security concerns. The Turkish company was replaced by a local consortium.

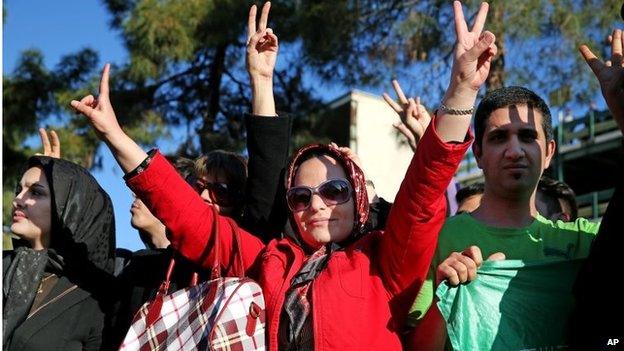

Ordinary Iranians were jubilant at the outcome of the talks, and the prospect of an end to sanctions

This happened under the watch of reformist President Mohammad Khatami but instigated by institutions over which his government had no control.

His successor Hassan Rouhani could find himself in the same situation.

"Did any of these stop multi-billion companies from rushing to China? Were they put off by shaky rule of law, violence or the military government in Egypt?" asks Emanuele Ottolenghi of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a US-based think tank that advocated increased sanctions against Iran.

"No, for those companies, it is just another risk to factor in, but won't stop them from going in."

Foreign investors flock to any forum that sheds light on the sometimes murky business mechanisms of the Iranian market.

"Rather than speculating from the sidelines about the Iran 'gold rush', we need business leaders to think like stakeholders who will constructively shape Iran's future," says Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, who helped organise an investment conference on Iran in London last November.

He is already planning the second Europe-Iran Forum, this time focusing on Iran's banking and financial sectors, in Geneva in September.

"Such forums allow us to encourage transparent conversations between Iranian and foreign firms on this common goal," says Mr Batmanghelidj.

The Iranian Ministry of Petroleum is also planning a major conference in London in September, where new oil contracts will be showcased for global energy giants.

Road ahead

But not all is final. The road ahead for nuclear negotiators is tough.

If putting out what is in effect a press statement could take the two sides four months of day-long talks and over-nighters, what could hammering out the details entail?

Opposition to the deal is strong, especially from Israel's Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and there is a chance it may not see the light of day on 1 July.

"I see that as a very remote possibility," says Mr Kamangar. "If the deal does indeed fall through, we are a very patient bunch and believe in the unique long-term potential of the country."