Could Christianity be driven from Middle East?

- Published

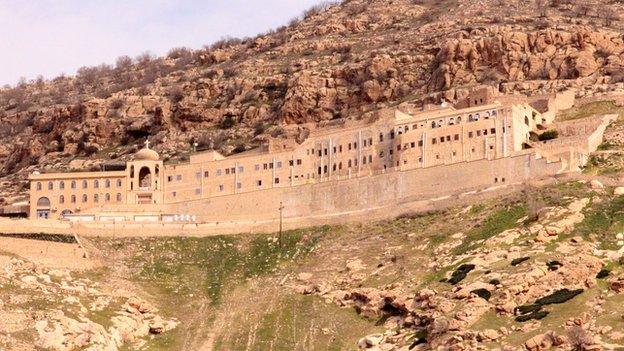

Monastery of Mar Mattai/St Matthew on Mount Alfaf, northern Iraq

Can Christianity survive, in the face of persecution and conflict, in the region of its birth? The BBC's Jane Corbin travelled across the Middle East - through Iraq and Syria - to investigate the plight of Christians, as hundreds of thousands flee Islamic militancy in the region.

As I climbed the steep mountain path above the plain of Nineveh, Iraq, the sound of monks chanting and the smell of incense drifted out of the 4th Century monastery of St Matthew. Once, 7,000 monks worshipped here when Christianity was the official religion of the Roman empire.

Almost the whole population was Christian then. Their numbers have dwindled and now there are only six monks - and no pilgrims dare to visit. "We are on the frontline with Isis and people are afraid to come here," Father Yusuf told me. "We are worried about everything: our people, our family, Christianity."

Kurdish fighters guard the monastery and on the plain I heard artillery fire and saw plumes of smoke from Western airstrikes on the positions of IS, the so-called Islamic State. They swept across the plain of Nineveh last year, forcing tens of thousands of Christians to flee from Mosul, Iraq's second city, and surrounding towns and villages.

There is no school for the child refugees but Father Yusuf tries to keep them busy

A handful of families have taken refuge in the monastery, as Christians have done for centuries since Islamic armies first swept across the plain in the 7th Century with the Arab conquest.

Thirteen-year-old Nardine is all too aware of what IS fighters do to girls they regard as infidels. "They are very cruel, they are very harsh," Nardine whispered fearfully. "Everyone knows, they took the Yazidi girls and sold them in the market."

"Isis have no mercy for anyone. They select women to rape them," said Nardine's mother. "We were afraid for our daughters so we ran away."

When IS declared their caliphate (Islamic state) last year with beheadings - even crucifixions - thousands of Christians fled in terror.

All six members of Nardine's family live together in a monk's cell

IS want to impose their brutal version of Islam and have sworn to purify the region of infidels, targeting Christians and other minorities.

The Peshmerga (Muslim Kurdish fighters) took me to their front line with IS, a few miles from the monastery where they are holding back the advance of the Islamic militants who have killed many Muslims.

The Kurds do not agree with the extreme form of Islam that IS espouses and the Peshmerga general assured me they would protect the Christians. "We lived here for many years as brothers - there is no difference between Kurds, Muslims and Christians different religions in Kurdistan," said General Hameed Afandi.

In Erbil in Kurdistan, thousands of displaced Christians are crammed into a half-built shopping mall. I met Leila and Imad Aziz preparing food for a Christian festival with their two little girls. They fled from Mosul last summer when IS occupied the city, giving Christians the choice of converting to Islam, leaving the city or paying the jizya - the heavy tax imposed on Christian subjects by Muslim rulers centuries ago.

"We can't go back to Mosul for fear of being killed, kidnapped or robbed," Imad told me. "I believe that in four to five years, very few Christians will remain. They will be pointing fingers at them saying: 'He's a Christian.'"

Leila crossed herself as she remembers how they were forced to pass through IS roadblocks where everything was taken from them - money, jewellery, even clothes. "We can't ever return to Mosul as we have nothing left there," she says.

Once the family had their own successful business and a nice home. Now all they have is a few battered photos to remember their former life.

In St Ilyas church, Erbil, I met Father Douglas Bazi - a Catholic priest who is caring for 135 families in tents in the gardens of the church.

"We are Christian, so we are used to having our luggage always prepared," said Father Douglas. "We always have to run away - escape from place to place."

This wave of persecution began not with IS but when Britain and America invaded Iraq in 2003 to topple Saddam Hussein. Under his rule, Christians were free to worship and played a full role in this society.

"Saddam's era was the golden age for Christians," said Father Douglas, although he adds that he did not personally agree with Saddam's rule.

As the Western coalition failed to provide security for Iraq, it descended into chaos and Christians became victims of the ugly sectarian power struggle unleashed between Shia and Sunni Muslims.

Father Douglas was held hostage for nine days, beaten and tortured until the Church paid a ransom

"They looked at the West as infidels and as Christians we were seen in the same way," Father Douglas explained. The priest's church in Baghdad was bombed and he was taken hostage by a militia and held until the Church paid a ransom.

Father Douglas shows me the blood-stained shirt he was captured in and described how his captors broke his back with a hammer, then his teeth - one by one.

"If you look at history, we are the same group who lose every time," he continued. "They push us to lose our faith, our people, our role, our positions, our job, now we have lost our homes - so what next?"

A million people, two-thirds of Iraq's Christians, fled in the decade following the fall of Saddam.

The same story is being repeated across the Middle East, where the Arab Spring unleashed forces that turned against Christians and the authoritarian leaders who once protected them.

In Syria, much of the ancient town of Maaloula still lies in ruins after months of fierce fighting in 2013 between Islamic militants allied to al-Qaeda and the regime forces of President Bashar al-Assad.

Three thousand Christians fled when the militants occupied this ancient place of pilgrimage, one of only three places in the world where they still speak Aramaic - the language of Jesus Christ.

Government forces initially withdrew from Maaloula leaving the Christians, some claim, to their fate. But eventually the regime retook the town and a few Christians are beginning to trickle back.

Antoinette Nasrullah was one of 3,000 Christians who fled Maaloula when it came under attack

Antoinette Nasrullah took me to what is left of her home and business, a cafe once popular with tourists. Now it is just a roofless wreck.

"It was my dream," Antoinette says, breaking down in tears. "We never believed the Muslims would do this to us… but we have to be strong and thank God we are alive."

Muslim families from Maaloula fled the fighting too but have not been allowed to return to their homes. The Christians accuse them of helping the militants.

The 6th Century monastery of St Sergius was occupied by rebels and Antoinette showed me smashed treasures and bullets through the faces of the icons.

"They stole icons very rich in history," Antoinette explained. "We are very sad about the icons. It affects us very much."

More than 200,000 people have died in Syria's four years of civil war. They are overwhelmingly Muslim, many killed by the regime. President Assad himself visited the monastery when his troops retook the town. He needs the Christians to support him.

Maaloula was seen by many Christians in Syria as a turning point. They have had to make hard choices and many have now put their faith in the regime as the only option if their religion is to survive.

"The government are the only ones who can help the Christians stay in Syria," says Antoinette. "Maaloula is in my heart, I cannot leave it because if there are no Christians in Maaloula, I think there will be no Christians in Syria."

Church leaders in the West have called for concrete steps to be taken to protect Christians in the Middle East.

It is hard to know what those steps would be beyond the airstrikes, military training and special forces operations already in place.

There is no appetite for more Western boots on the ground.

In Erbil, Father Douglas believes it may already be too late for Christianity to survive here.

The West, instead of urging Christians to stay in Iraq, should help them leave. "Open the gates, give my people visas," said the priest. "We have to provide them with dignity and the right life - not prepare them to be sheep, again to be killed."

This World: Kill The Christians will be broadcast on BBC Two on Wednesday 15 April at 21:00 BST, or catch up via BBC iPlayer.

- Published11 October 2011