Iraq: Growth of the Shia militia

- Published

When Islamic State (IS) seized control of Iraq's second largest city, Mosul, in June 2014, along with other parts of the predominantly Sunni Arab north-west, Iraq's Shia militia were mobilised to launch a counter-offensive against the jihadists.

The collapse of Iraq's armed forces in the face of the IS advance led to these militia playing a pivotal role in government security operations over the past year, most notably in Tikrit.

However, they have also come under criticism for alleged human rights abuses, a charge their commanders deny.

Anti-Saddam

Iraq's Shia militia are part of a broader mobilisation of the majority Shia community, which has traditionally aimed to contest power in the country and, prior to 2003, remedy the Shia's history of oppression at the hands of the Iraqi state.

Shia mobilisation and activism in Iraq intensified with the Baathist coup in 1968 and the regime's collective suppression of the community, although some Shia were co-opted.

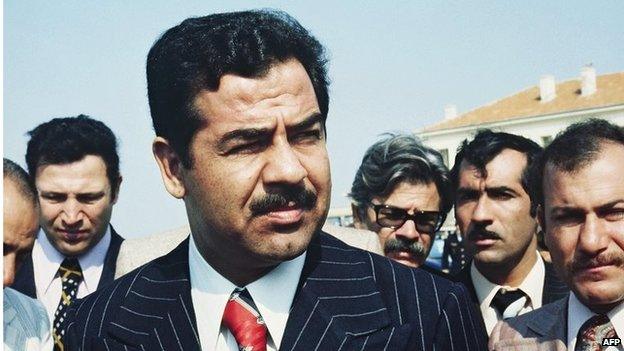

Iraq's majority Shia community was suppressed under Saddam Hussein

After the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran, Shia actors, like the Islamic Dawa Party (of Iraq's current prime minister), mobilised the Shia community to try to overthrow the Baath regime but the attempt failed.

The 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war then saw various Shia groups take up arms against Saddam Hussein, with patronage from Iran, but this was to no avail as neither side was able to defeat the other during the costly war of attrition.

Another rebellion was launched in 1991, following the first Gulf War. Looking to capitalise on a weakened Iraqi army, as well as an apparent endorsement from then US President George HW Bush, Iraqi Shia launched an uprising in mainly Shia provinces of the south.

But no US support materialised and the regime's indiscriminate crackdown on the population saw tens of thousands killed. Shia shrines, centres of learning and communities were also destroyed.

Post-invasion

Following the fall of Saddam Hussein, Shia fighters that had previously fought the Baath regime were integrated into the reconstituted Iraqi army and the country's police force.

However, some also remained militia members and fought a sectarian war with Sunni militants, which reached its apex in 2006.

Shia militia played a key role in recapturing Tikrit from Islamic State in March

As a result of sectarian warfare and disastrous post-conflict reconstruction, Shia militia that functioned independently of the state became increasingly widespread and powerful.

They were responsible for much of the lawlessness and crime in the country, including attacks on US and British occupation forces, as well as Western civilians working in Iraq.

Shia militia have their own differences and fought one another over the past decade. However, when IS seized control of much of northern and western Iraq they unified as part of a concerted effort to defend their country and places of worship.

This is not to say that intra-Shia clashes will not take place again in the future.

To swell the ranks of the anti-IS forces, in the absence of a functioning Iraqi army, Iraq's Grand Ayatollah Sistani, the leading cleric in the Shia world, issued a religious edict calling on Iraqis to take up arms.

Tens of thousands of Shia volunteers, as well as many Sunni tribal fighters, were immediately mobilised as a result to form what is known as the Popular Mobilisation. The Washington Post reports that Shia militia comprise up to 120,000 fighters, external.

Iranian backing

The proliferation of Shia militia in Iraq after 2003 was also fuelled by the support Iran gave Shia bodies willing to act as its proxies.

Iran has actively supported Iraq's Shia groups since 1979. The most powerful militia group in Iraq today is the Badr Brigade, which was formed in and by Iran in the early 1980s, during the Iran-Iraq war.

Iran has considerable influence over Iraq's Shia militia because of its heavy on-the-ground presence.

Shia volunteers answered a call from Iraq's Grand Ayatollah Sistani to take up arms to defend the country

Iran was the only outside power that deployed advisers and special forces in the country when IS took control of Mosul and directly organised the anti-IS offensive.

However, it does not have the same level of influence over all militia.

The Badr Brigade, whilst considerably close to Iran, could still function without Iranian support and has done so before, given its entrenchment in the Iraqi state (its head, Hadi al-Ameri, is a former Transport Minister).

A large number of the militia in the Popular Mobilisation also report to local Iraqi figures, as opposed to Iran.

On the other hand, weaker splinter groups which emerged after 2003 are more dependent on Iranian support and some are widely reported to be receiving orders directly from Iran.

In the near future, Iraq is likely to continue to depend on the militias to contain IS and maintain security in the country.

While Iraq's Shia militia cannot be eliminated, given their entrenchment within the Shia community and the Iraqi state, they can be regulated but that is only likely to happen once the threat from IS has abated and the country has a fully functioning army.

Ranj Alaaldin is a Visiting Scholar at Columbia University and a Doctoral Researcher at the London School of Economics, where he specialises in Iraqi history and politics. His research currently looks at the history of Iraq's Shia movements. Follow him @RanjAlaaldin, external